Taylor Swift sent shockwaves around the world in multiple ways with her devoted fans and packed Eras concert tour venues. She also has been setting off so-called SwiftQuakes and now scientists know why.

It wasn’t the drumbeat or the deep base guitar amplified over the sound system or even Swift herself hitting the high notes. The tremors were caused by the thousands of dancing fans, scientists found.

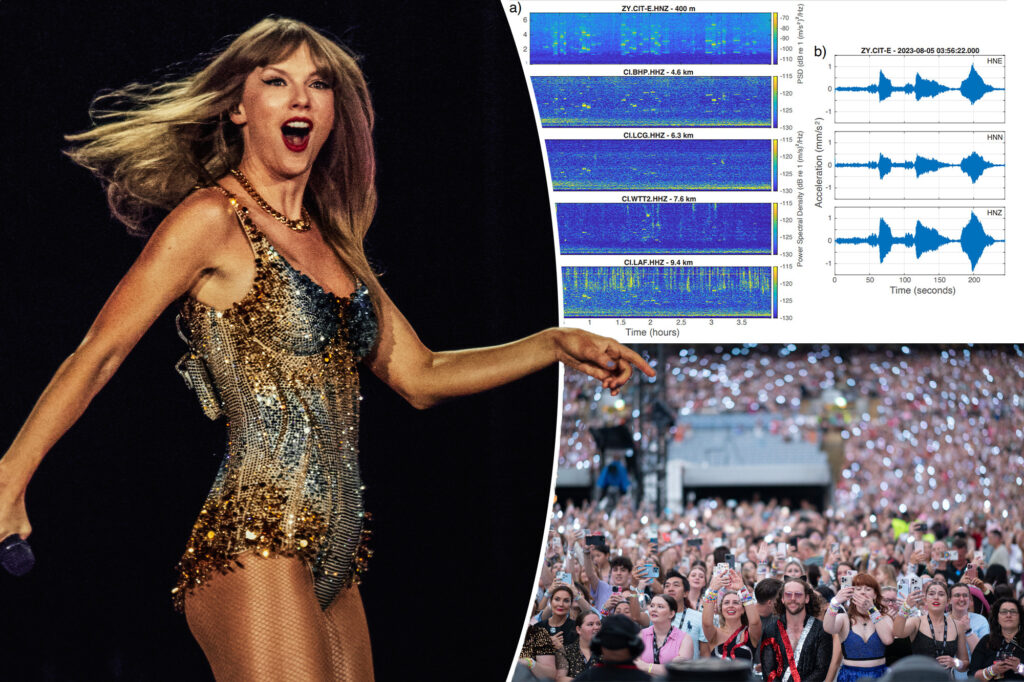

The late July concert that went viral after it registered on a Seattle seismograph made the California Office of Emergency Services take notice. They contacted the California Institute of Technology to set up strong motion or seismic sensors in and around Los Angeles’ SoFi Stadium for Swift’s series of concerts in early August.

The team also monitored quake meters within 5.5 miles of the stadium. The stadium complex sits within the Newport-Inglewood fault system which is capable of generating magnitude 7-plus quakes.

Gabrielle Tepp, author and amateur bass guitarist, said that the harmonics of the “concert tremor” that was recorded look a lot like those from volcanoes or trains, not quakes. They were low frequency and not heard by the human ear. Large music festivals and stadium concerts produce similar vibration signals that resemble a harmonic tremor.

The biggest bang came when Swift sang “Shake It Off.” The tremor was equivalent to about a magnitude 2 quake. Instead of using magnitude, which is energy given off in a moment, scientists measured radiant energy, which is given off over time, for example, during a song. Tepp dubbed it “song strength.”

Swift’s top earth-shaking songs

After conversions done based on an American Geophysical Union study, these are the the top five energy-releasing songs from Swift:

- Shake It Off – about magnitude 1.798.

- You Belong With Me – about magnitude 1.796.

- Love Story – about magnitude 1.76.

- Cruel Summer – about magnitude 1.71.

- 22 – about magnitude 1.64.

“Keep in mind this energy was released over a few minutes compared to a second for an earthquake of that size,” Tepp said in a news release. “Based on the maximum strength of shaking, the strongest tremor was equivalent to a magnitude 2 earthquake.”

She could identify 43 or 45 songs just by looking at the spectrograms – a graph of the strength of various signal frequencies overtime. The other two songs did not register.

“My gut feeling was that if you have a harmonic signal that is nice like these, it had to be from the music or the instruments or something,” Tepp said, admitting that her initial thoughts were wrong.

She was so surprised that she set up her own trial, playing Swift’s music over a PA next to a motion sensor. Then she grabbed her own guitar and rocked out to her own version of “Love Story.” It was not her bass beats that triggered the motion sensor.

“Even though I was not great at staying in the same place, I ended up jumping around in a small circle, like at a concert,” Tepp said. “I was surprised at how clear the signal came out.”

She said bass beats are rounder on the spectrogram, while jumping creates spikes.

Now, imagine the 70,000 Swifites all jumping together to “Shake It Off.”

“The structural response of the stadium showed nearly equal shaking intensities in the vertical and horizontal directions at frequencies that match the seismic signals recorded outside the stadium,” the study said. “All evidence considered, we interpret the signal source as primarily crowd motion in response to the music.”

Different genres of music shake the earth differently

She compared the data to that from a Metallica concert which showed weak seismic signals despite similar instruments.

“Metal bands, in general, tend to play ‘in the moment’ and are less likely to stick to a beat (or an album recording) compared to the highly choreographed shows of Swift and Beyoncé, or that metal fans may move in a manner that’s less amenable to generating steady vibrations,” the study said. “The heavy metal band’s beat rates are ‘all over the map’ while Swift’s are all very similar and the concert is highly choreographed.”

“Metal fans like to headbang a lot, so they’re not necessarily bouncing,” Tepp added. “It might just be that the ways in which they move don’t create as strong of a signal.”