On the Shelf

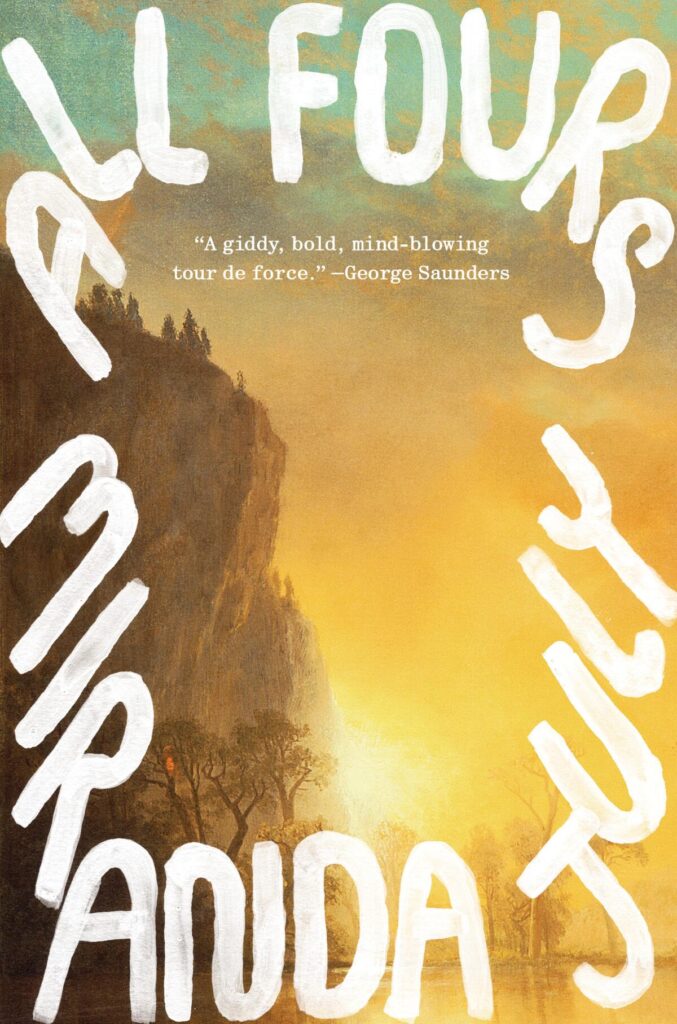

All Fours

By Miranda July

Riverhead: 336 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Miranda July is known for her whimsical characters and uncanny, intimate stories of what it means to be human. Her first major film, “Me and You and Everyone We Know,” premiered to acclaim in 2005, and a collection of short fiction, “No One Belongs Here More than You,” won the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award upon its publication in 2007. With a background rooted in DIY, zines, video and performance art, it’s easy to spot July’s influence on the zeitgeist, especially in the practice of “being online,” in memes, social media and other performances, public or personal.

July has hit a creative, life-giving stride, at 50, with her new novel, “All Fours” — her first since 2015’s “The First Bad Man.” A visit to her new home/old office in Los Angeles, just before her appearance at the L.A. Times Festival of Books, revealed a place chock-full of creative energy. July has been renovating a new living space with her trademark joy. It was obvious how much pleasure she takes in her new butter-colored cabinets and artworks from friends. After celebrating her 50th birthday in February, July flew to Milan to launch her first solo museum exhibition, “New Society,” at the Prada Foundation, giving her just enough time to race back to the States for the publication of “All Fours” on Tuesday.

“It’s not getting more boring,” she says about life. “It’s only getting weirder and weirder!”

Speaking about the genesis of the novel, which tells the story of a “semi-famous” artist who decides to take a road trip from L.A. to New York, leaving her husband and child at home, but instead pulls into a hotel less than an hour from L.A. and falls in love with a car rental employee, July found a tender spot in her life when it came to getting older.

“I’m the kind of person who is always excited about my future and it seems like there’s a lot to hope for,” July said. “But around 40, I started to get worried about the coming years. When I looked forward, it looked shocking … it was a narrowing and dimming of the road ahead. What was it going to be like for my body, my face, my sexuality? My conversations with other women were getting more radical and everyone was questioning everything. But it’s all this whisper network. Because, the shame. The shame is like this cork that’s holding all of this vivid life back.”

“All Fours” began as a chronicle of women’s lived experiences, with each chapter bearing the name of a different woman. July had thousands and thousands of notes on her phone with anecdotes from real life, “fleecing them for the narrator,” she said. Ultimately, the book changed form. “Fiction is my superpower,” July said, “all my previous work is super character-y. But there were some moments in ‘The First Bad Man’ that were more honest, more personal, and they were some of my favorite moments in the book. I thought, ‘I want to take that further.’”

The result is a novel that presses into that tender bruise about the anxiety of aging, of what it means to have a female body that is aging, and wanting the freedom to live a fuller life. Like all of July’s work, “All Fours” is a wild ride. It is deeply funny and achingly true. On what she feels is her marital responsibility to her husband, the narrator tells readers “sometimes I could hear Harris’s dick whistling impatiently like a teakettle, at higher and higher pitches until I finally couldn’t take it and so I initiated.” While making lunch for her child, she relates: “The problem wasn’t the lunch, it was what came after, the whole rest of my life.” When she feels shame about spending hours on the phone with her best friend, Jordi, she remembers: “It was my one chance a week to be myself.”

July’s fans may realize that the “semi-famous” narrator of “All Fours” and July have much in common. July posted on Instagram in 2022 that she and her husband, filmmaker Mike Mills, had separated romantically but were still a loving family. But she’s not too worried about the autobiographical nature of the book. “Map me on to the character, that’s fine. I could write like this forever. It’s like a character played by me. I can do anything I want with her. Compared to other writers, like my friend Sheila Heti or writers like Annie Ernaux, I feel very old-school nerdy because I’m coming up with characters and plot twists and I’m a little Hollywood in my love of a big reveal!”

That said, incorporating her personal experience into the book proved difficult. July works continuously and energetically on her craft. “I was writing at pace with my life,” she said. “There were perspective shifts that I would have that I would want my character to have that usually I would have months or even years to process before turning it into fiction. By the end, I was writing and throwing things out to get to the level of writing fiction. But I’m so proud that I did ride the wave and it took me to a fictional shore that felt like my truth.”

When asked how writing a book differs from other media, July said she felt like it was another kind of performance. “So much of writing is improv — you are improvising on the page. I do a lot of reading out loud, and I can hear where the reader is a little confused. There’s a ‘will it play’ quality that you ask about in performance, and there’s that feeling with the reader too.”

There is a bit of magic involved in making that connection. July looks forward to readers absorbing her book once it’s out into the world. Her last film, “Kajillionaire,” was released during the pandemic, and it was the first time she read reactions in her DMs. “I asked everyone if I could screenshot and post their responses because everyone felt so alone, and I wanted them to see that they are not alone because their responses were so similar. That’s useful for me — the feeling that you threw the ball out and it was caught. It’s not falling forever through space.”

Reading “All Fours” feels like being seen, like being caught and held, making those connections and realizing that our experiences are not so isolating — in fact, that the narrowing and dimming of the road ahead is like a movie set. It looks real from the front, but behind there’s nothing of substance. Nothing to be afraid of. July’s commitment to widening the space when it comes to our sexuality is joyfully radical.

“Often when I finish a project, I’m like, ‘Whew! Thank God I don’t have to work in that medium for a while!’ But I don’t have that with this book,” July said. “It’s a bit confusing because this is not my creative pattern but the voice of the narrator is still with me. I was joking with a friend, I said, ‘What am I going to do, write “All Fives?”’ That would be a terrible title.”

Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”