When Mike Appel — Bruce Springsteen’s first producer and manager — initially heard the 22-year-old baby Boss in November 1971, he wasn’t impressed.

“He sang two songs at the piano … and they were two songs that were just blah, nothing,” Appel told The Post about Springsteen’s audition. “I said, ‘Is that all you have?’ He says, ‘Well, that’s all I have at the moment.’ I said, ‘Well, if you’re gonna wanna do an album, you’re gonna have to have more songs — and they’re gonna have to be better than these.’”

Three months later, Springsteen returned to Appel’s Laurel Canyon Productions office in Midtown Manhattan strapped with his guitar and a bunch of new tunes. “The first one he plays is ‘It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City,’” said Appel. “That crushed me. It was love at first hearing because the words were so special. And I said, ‘You gotta sing this again, ’cause I wanna make sure you’re saying what you’re saying.’”

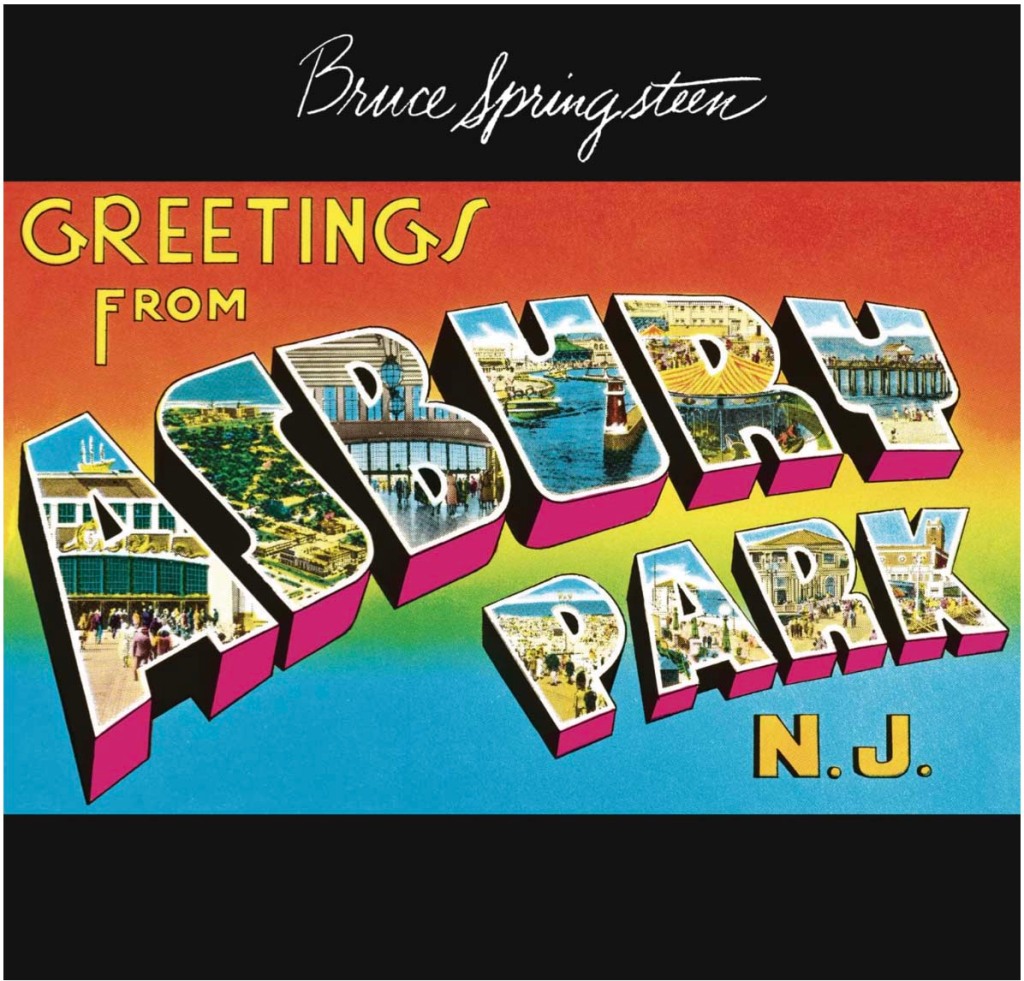

“It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” would turn out to be a genuine godsend for Springsteen, who recorded the poetic tune for his debut album, “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.” — released 50 years ago on Jan. 5, 1973. It launched a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame career that is still running strong 20 LPs later for the 73-year-old New Jersey native.

But on “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.,” you hear the genesis of a young genius who is showing both his age and ambition on songs ranging from the youthful “Growin’ Up” to the yearning “For You.” “What’s great about it is, it’s not too much, it’s not too little,” said Appel. “That’s where you are at that stage, Bruce. That’s you.”

The LP’s title was inspired by the beach town where the Long Branch-born, Freehold-bred Springsteen got schooled in rock as a teenager playing in clubs such as the Student Prince, the Sunshine In and the Upstage Club. The latter venue is where Springsteen connected with some “Greetings” players — keyboardist David Sancious, bassist Garry Tallent and drummer Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez — who would go on to become original E Street Band members.

In fact, Sancious played a key role in coming up with the band’s mythic moniker. “That was the street that I grew up on in Belmar, New Jersey,” Sancious told The Post. “It was very mixed racially and religiously, but it was very peaceful. My mother used to let us rehearse there [at home] occasionally. And I think he just liked the sound of it.”

After playing in the band Steel Mill (originally called Child) with Lopez and other future E Streeters Steven Van Zandt (guitar) and Danny Federici, Springsteen was signed as a solo artist to Appel’s Laurel Canyon Productions and then Columbia Records — by legendary music man Clive Davis — in 1972. The label gave its new artist and his producers, Appel and then-partner Jim Cretecos, space to create.

“I was given carte blanche,” said Appel. “And I thought that what we could do is to get Bruce’s music writing up to where the lyrics were, so that the arrangements could be a little bit more sophisticated, more original and more identifiable.”

Although Springsteen was originally anointed as “the next Bob Dylan,” Davis suggested that they beef up the arrangements. “Clive said, ‘You got a lot of songs here just with Bruce acoustic. There’s no reason we shouldn’t have maybe a little band behind Bruce,’” said Appel.

Enter the E Street Band. Lopez remembers getting the fateful call from Springsteen to play on his debut. “I was working in a boatyard,” Lopez told The Post. “And the owner comes in one day, and he says, ‘Hey, there’s this guy Bruce on the phone’ … And he says, ‘Hey, I got a record deal. We’re gonna record now. Well, do you wanna do it?’ I said, ‘Sure!’”

But longtime sideman Van Zandt didn’t make the cut on guitar. “Stevie Van Zandt was there for a little bit in the beginning,” said Appel. “But then Bruce, I think, figured he would play the leads, and so Stevie wouldn’t be necessary … Bruce is a pretty competent electric guitar player, so I didn’t know what the heck this guy is gonna do necessarily.”

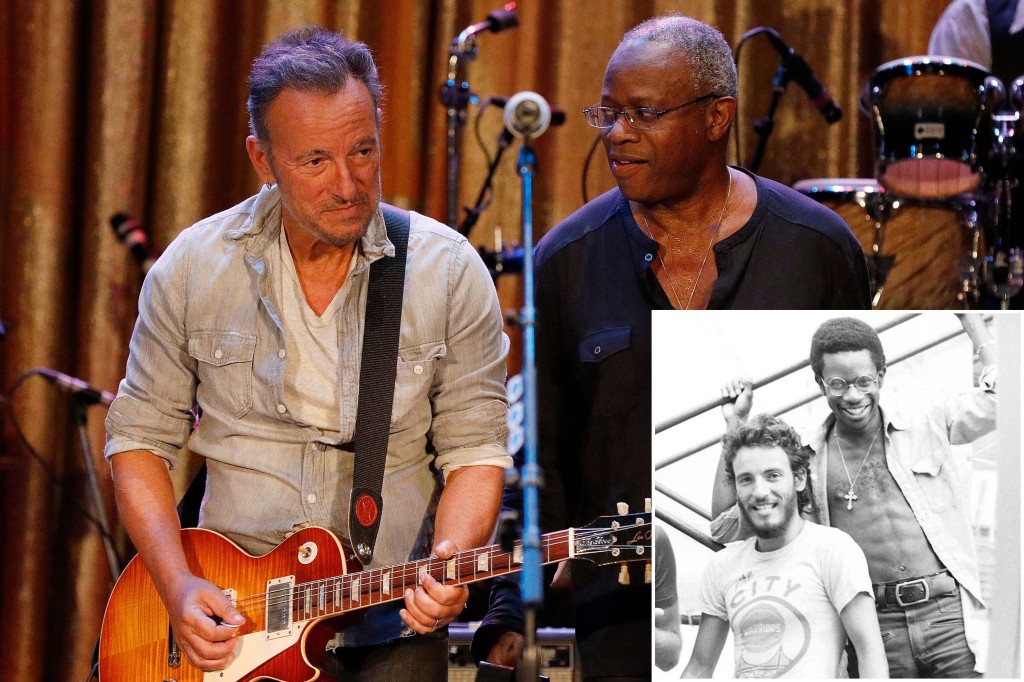

Lopez recalls pulling double duty with saxophonist Clarence Clemons on some androgynous backing vocals: “Singing with Clarence on ‘Spirit in the Night’ … everybody thought there were girls in the band sometimes, but there weren’t. It was me and Clarence.”

Appel tricked the Big Man into calming his nerves at 914 Sound Recording Studios in Blauvelt, New York, where the album was recorded over the course of five months. “His saxophone was squeaking all over the place,” he said. “I had isolated Clarence where everybody [else] was in the control room, and so I said to myself, ‘He may be one of these guys that has to play his parts live with the other guys. So leave all the other guys mics off, and you’ll only have his microphone on.’ ”

Springsteen, though, was “never nervous in his life,” said Appel, who went on to produce 1973’s “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle” and 1975’s “Born to Run.”

“He was the Boss,” he added.

In fact, it was the Boss who got Appel to sing on first single “Blinded by the Light.” “He stops the session: ‘Mike, why don’t you come out here and sing it with me?’ And the two of us are singing in unison on the choruses.”

Springsteen was in such control that he even came up with the iconic album cover design. “He walks in the office one day and has a postcard from Asbury Park,” said Appel. “He hands it to me, and he says, ‘What do you think about this for the cover?’ I said, ‘This is nice and cheap and tawdry and boardwalk-y. This is rock and roll.’”

And “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.” helped give New Jersey a more prestigious place on the music map.

“It is the spirit of the Jersey Shore,” said Eileen Chapman, Director of the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music at Monmouth University, which will hold The 50th Anniversary: Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. symposium on Saturday. “I think it [inspired] not only Jersey pride, but pride that somebody we knew actually had the opportunity to do what they love. There was just a lot of pride in Bruce.”