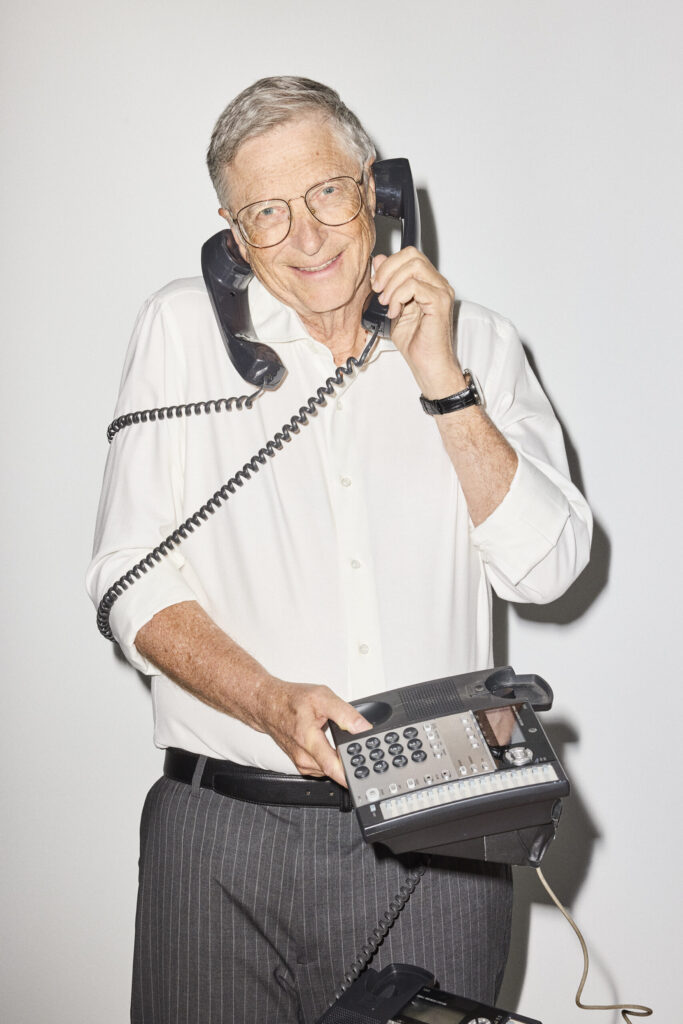

Bill Gates wears Shirt, Glasses (worn throughout), and Belt Bill’s Own. Pants Celine Homme By Hedi Slimane. Watch Omega.

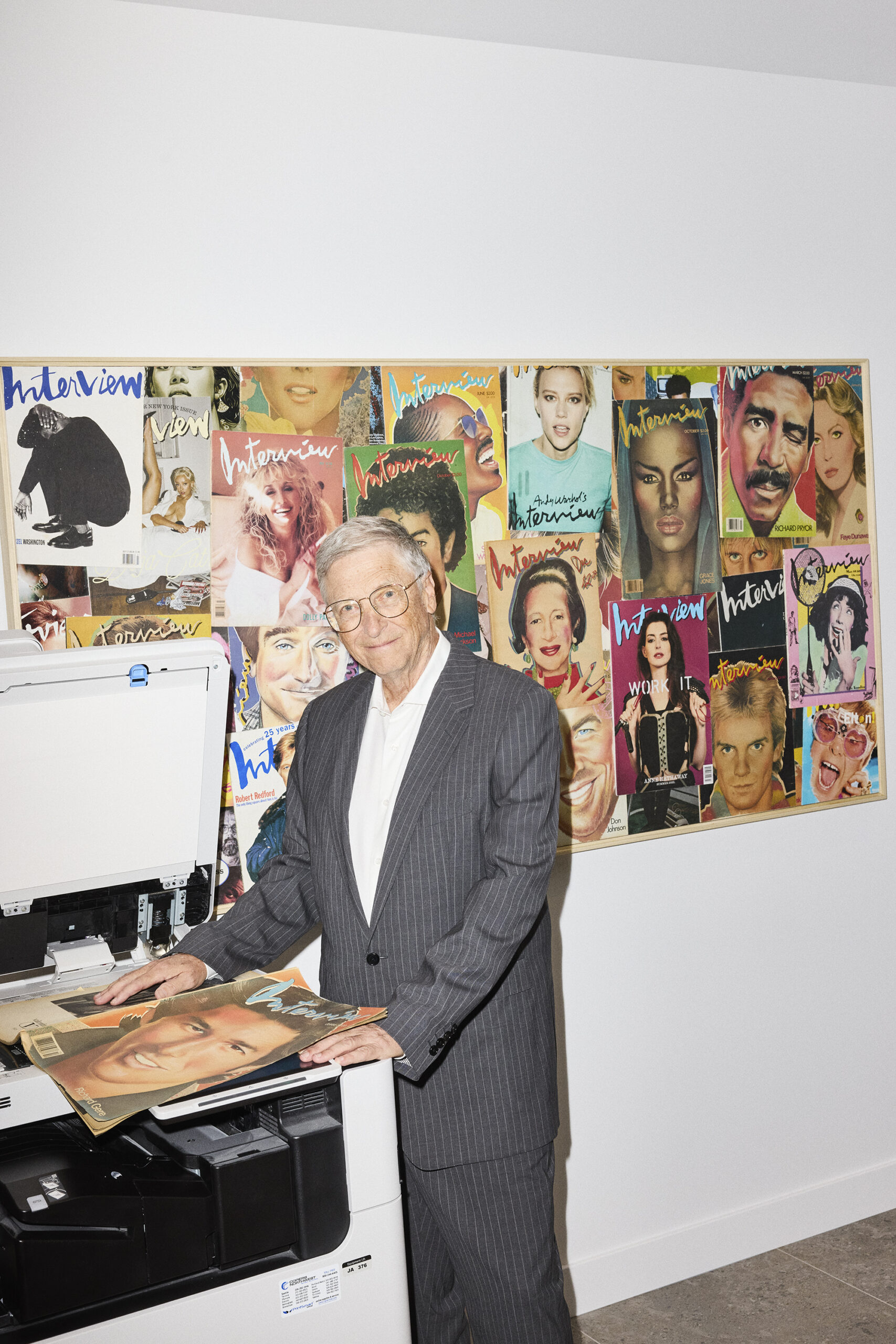

Before Bill Gates revolutionized personal computing, before he democratized access to tech, and before his foundation took on some of the world’s biggest woes, he was just a scrawny boy who liked to play card games with his grandmother and hike in the mountains around his hometown of Seattle. The cofounder of Microsoft had to start somewhere, and in his new memoir, Source Code: My Beginnings, the 69-year-old former world’s richest person details those humble beginnings, opening up about his upbringing with a strict mother and continuing all the way to his days at Harvard with childhood friend Paul Allen as they sought a breakthrough amid the early rush of computer technology. “Such was the dawn of the personal computer revolution,” he writes of the scrambling ambition in their dorm rooms. “We all were just faking our way along.” Gates has been friends with the writer (and the ultimate biographer of scrappy geniuses) Walter Isaacson for more than 40 years. They got a chance to talk just before Gates got ready for his photo shoot at his office in Palm Desert, California, surrounded by his collection of Interview magazines.

———

TUESDAY 1 PM DEC. 17, 2024 PALM DESERT, CA

WALTER ISAACSON: Hey, Bill. Good to see you. That was a really fun evening we had the other night.

BILL GATES: Yeah, it’s super great that worked out.

ISAACSON: This is supposed to be very conversational, so we’ll try to act relaxed. I just read your memoirs and one of the amazing things you talk about is how your brain works differently than other people’s. When did you first discover that?

GATES: I was pretty young when I could see my level of curiosity and ability to focus on something for long periods of time was a bit un-usual. I remember in fourth grade the school had a record player that would play math problems-like 18 plus 13 and then you had to write it down. It wasn’t even going that fast. But I was like, “Wow, everybody’s kind of panicked. I guess I have a speed advantage on these fairly simple math problems.” I also remember that 1 did a report on the state of Delaware and ended up doing this massive thing because I got kind of obsessed with it. So I knew that I liked things to make sense pretty early on. I also knew that my social skills weren’t the best, so I was always a little bit awkward with kids my age.

ISAACSON: Speaking of becoming obsessed with Delaware, I know you’re obsessed with tiny objects, and I guess Delaware counts as the second-tiniest state. You just talked about missing social cues. If you were born today, do you think you’d have been diagnosed on the autism spectrum? And in some ways, were those traits superpowers rather than handicaps for you?

GATES: Yeah, on balance, even though I felt a little out of place, it certainly was a huge contributor to my developing confidence men-tally. It also helped in studying software at a time when that was about to become super important and super valuable. My parents sent me to a therapist, which was very unusual, but not for any specific diagnosis, just that they thought this therapist could convince me to be a little less tough on them and to have a little more peacefulness in the house. When they first sent me, I thought, “Oh, that’s not going to work.” But in fact, the therapist was so enlightened and nice about giving me stuff to read. He actually framed the problem as, “Why are you in this conflict with your parents? The real conflict is you and the world and they’re kind of on your side.” That really made me think, “Yeah, he’s actually right about that. Why am I putting so much energy into saying that my parents’ rules are irrational?” Terms like the autism spectrum or neurodiversity weren’t used much in those days. Nobody ever even considered that I should take ADHD medicine or anything like that.

Suit Celine Homme by Hedi Slimane. Shirt Bill’s Own.

ISAACSON: Do you think that’s a good thing? What if you had been treated with drugs like kids today are?

GATES: It’s hard to say. If they’d told me to behave normally and I’d gone along with that, I might not have sat in my room reading books at great length. My mom did not give up on encouraging me to talk to the adults who came over to the house. So actually, this idea of talking through real-world problems with adults and understanding the work they were doing came in very handy for me as I was going off and working on different software projects.

ISAACSON: One of the things the therapist told you, which struck me as the most important piece of advice you can get, is to just remember you’re a lucky kid.

GATES: I was so unbelievably lucky both with my parents and with the time that I was born in. My parents decided they would invest in private school tuition, so I was sent off to a school called Lakeside, which happened to be a place with really great teachers that spent a disproportionate amount of time with me. That’s also where this machine, the teletype, where you could dial in and connect up to this big, quite expensive computer, shows up when I’m 13. By the time I was 18, I had massive exposure for doing software projects and having people who were very experienced give me advice.

ISAACSON: For the 40 years I’ve known you, you always rock back and forth in your chair. You’re doing it now. What’s that about?

GATES: It’s not a conscious thing. I guess when I get up inside my head, my physical body, in terms of comfort, just wants to do it. My parents do say they put me in a rocking bed and on a rocking horse and I would fall asleep. Maybe it’s some type of comfort thing. People around me often say, “Stop rocking,” because it makes them a little nervous. And I’m like, “Oh yeah, you’re right. I am rocking. Okay, I’ll stop.”

ISAACSON: I think it calms your mind a little bit. It’s like hiking. You were hiking as a kid and you started coding things on a hike.

GATES: I think it’s part of being very in my head and not paying attention to things. I do it subconsciously.

ISAACSON: I was surprised by how revealing the book is. Was it hard to share that much? What was the hardest part to write about?

GATES: I’ve always found it strange when things get a little mythological. Like, okay, if you’re really good, then you must’ve been way, way, way better than everyone else every step of the way. I was a very good math student and better than others, but if you’d said to my peer group, “Okay, one of you is going to be insanely successful,” it wasn’t that evident it would be me. I wanted to be straightforward about that and not create some myth. The people who helped me do all the fact-checking went back and got all my teacher reports and grades and talked to the people that I grew up with. So it’s an attempt to really say, although I was very lucky to find myself at the ground floor of the digital soft-ware, personal computer revolution, I just happened to have the right experience and the right confidence in order to drive it in a very intense way to build Microsoft into a leading company.

ISAACSON: Almost all of the people I write about who were successful geniuses were also rebels. They resisted authority. They challenged conventional thinking. And you talk about doing that with your mother. Looking at myself, I wasn’t that rebellious, I didn’t resist authority, so I think I ended up writing about famous people as opposed to being one. Do you think resisting authority helped you?

GATES: One of the big advantages of youth is that you get to think things through from scratch. And having a little bit of contrariness, where people say, “This is the only way this problem can be solved,” and you’re like, “I wonder, did they really think it through? Are people just accepting this? Maybe there’s a more efficient or better way to do this.” You get motivated to have a unique idea. And yes, that can lead you down the wrong path, but when Paul Allen said to me, “These chips are going to get exponentially better,” I was like, “Oh my god, the implications of that are unbelievable. How come other people don’t see this? Boy, we’re going to show them what the magic is here when you take those chips and combine them with some great software.”

ISAACSON: You’re talking about deciding to write BASIC for the Altair, one of the huge leaps in history that you took in figuring out that in the future it’s going to be about software, and that there will be a whole software industry. And in some ways you’d commoditize the hardware maker. How big of a deal is that? Do you think we’ve created generations that don’t have enough respect for hardware?

GATES: Hardware has been unbelievably enabling, whether it’s the chips or the optic fiber or the storage devices. But those industries have ended up being very competitive. And that’s why, in the dialogue with Paul Allen where he was saying, “Hey, let’s go build personal computers ourselves,” I was like, “Well, IBM and Japanese consumer electronics companies are going to be in that space.” The key insights there are that we’re not unique. And maybe the critical element is the software piece, that people will recognize that if a company was really the best at creating software, it would be very valuable. That’s what we enjoyed doing. That’s what we were unique at. And it did work out. To-day, you can say that amazing companies like Apple who work on both hardware and software have been able to do great things like the iPhone because they’re innovating on both sides. Microsoft had to build partnerships with hardware companies and chip companies in order to achieve that. So there are pluses and minuses, but the part I thought was so under-recognized was that software was key.

ISAACSON: You played a whole lot of cards with your grandmother when you were growing up. What did you learn from card games that applied to coding or to life?

GATES: When you first play cards, nobody says to you, “Hey, you’re supposed to remember all the cards that already went by”-how many tens or queens or sevens people have discarded so that if you’re collecting those for, say, gin rum-my, you’ve got to know what the state is. For a young mind, if you say, “Okay, I’m going to figure out the state of this thing,” it’s very, very doable. And I was puzzled as to why my grandmother was just so consistently beating us. And then I thought, “Okay, she’s got a state machine. She remembers what happened, and that has certain implications for what the best move is.” It’s kind of a mathematical thing. There was a lot of pleasure in slowly but surely being able to do that as well, and eventually even a little bit better than she did.

ISAACSON: I remember you came down to New Orleans for a book festival a year or two ago. I thought, well, that’s great. And then I realized you were there for a bridge tournament, too. Do you play bridge?

GATES: Of all the card games, the one that is the most complex in a fascinating way is bridge. Bridge used to be one of the most popular activities in America, but that’s way back in the 1930s. My parents taught me when I was young, and then through my friendship with Warren Buffett, he was playing a lot of bridge. So I went back in and actually got reasonably serious about becoming a decent player, and I still try to go to at least one national tournament every year. I was just at one for three days, playing bridge day and night, and reveling in when I did something well and giving myself a hard time when I didn’t get it right.

ISAACSON: Is bridge something that machines have been able to conquer?

GATES: No. I mean they could, like in chess-the best chess players are computers. Nobody’s actually taken the time to do that in bridge because understanding all the bids and what they imply is a little more complicated. But it definitely could be done.

ISAACSON: In writing this memoir, you said the more you dug in, the more you remembered. How is human memory fundamentally different from computer memory?

GATES: It’s unbelievable how good humans are at discarding unimportant information and retaining what’s important. We evolved to find food and not get lost, things like that. So I can remember all the early software almost line by line, because it was such an intense and important thing. And yet, if you’re in a meeting with four or five people, even 20 minutes later, if you say, “Okay, what was everybody wearing?” you probably won’t remember that. Whereas for the computer, because it has essentially infinite storage, it’s got an eidetic type memory where it’s all there. Hu- mans are so good at pruning the memory down. Going back, it was amazing how much, with a little prompting, I recalled all these wonderful episodes of growing up.

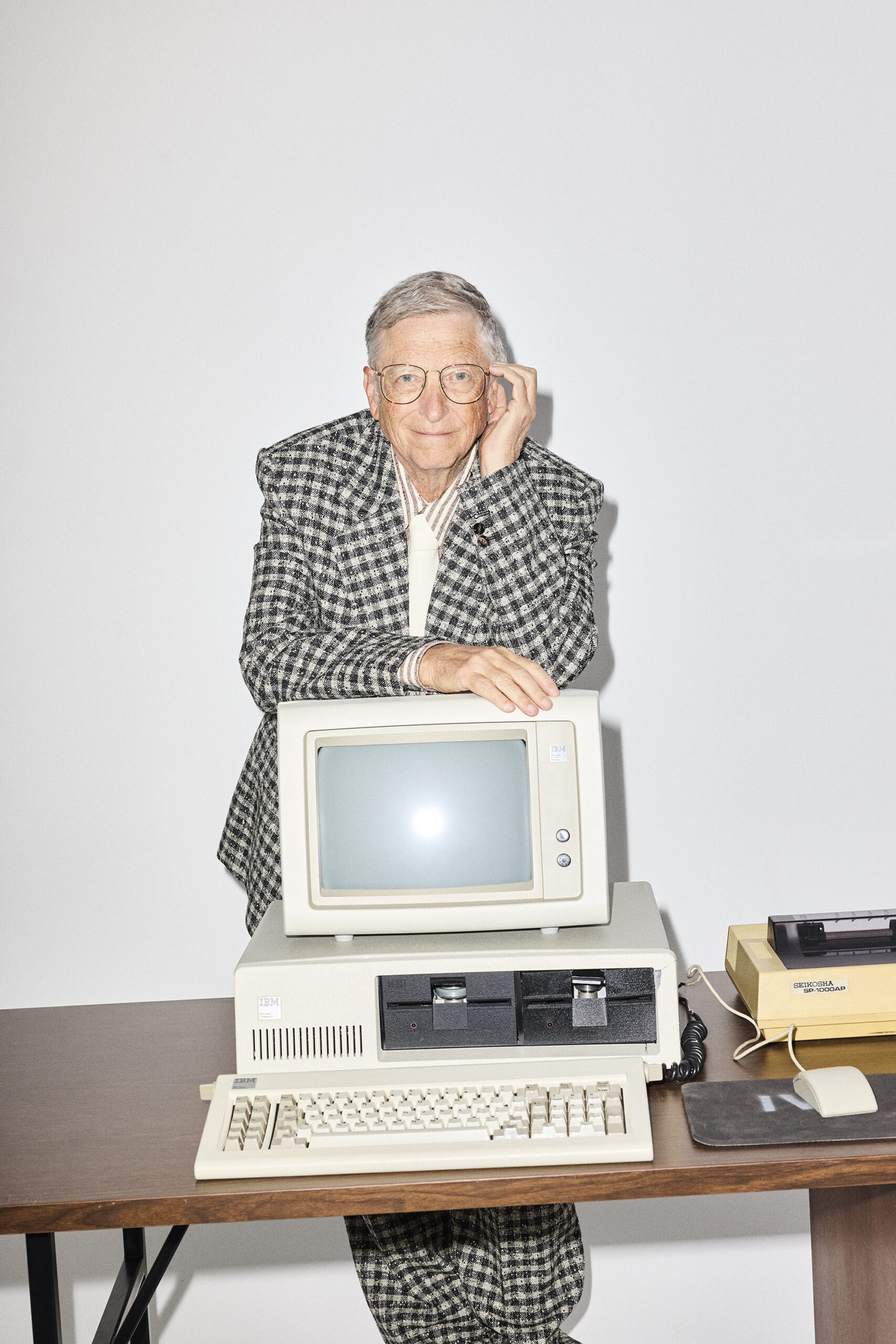

Suit, Shirt, and Tie Bottega Veneta.

ISAACSON: There is one episode where one of your friends gets interested in John D. Rockefeller and says, “He got really successful. And then he gave away all his money.” And you said, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.” When and why did you realize that it wasn’t the stupidest thing you’d ever heard?

GATES: Rockefeller did some great stuff, including his own foundation. Most people don’t realize it was incredibly enlightened. I studied that a lot before I started my own foundation in 1994.

ISAACSON: What would you be doing now if you were a young person when it comes to something like AI?

GATES: There are certainly a lot of innovative things that the world needs, whether it’s in diseases or clean climate technologies. But the most profound technology is AI, because it’s going to have such an impact on all the scientific work we do and even help do some of the jobs that we have to have humans do today. So I definitely recommend understanding where it works and where it doesn’t work, and there are going to be some great advances made in this next decade that make it, in some ways, even more important than the revolutions I got to be part of the digital revolution, the PC, the mobile phone, the internet. Now, of course, AI builds on all those, but in a sense it’s even more pro- found because it’s creating nonhuman intelligence.

ISAACSON: What will that be like in a hundred years?

GATES: It’s very difficult to predict because we’ve never had anything like this. I mean, people say that past advances have just broadened the job market, and people still work pretty long hours. But AI is kind of unbounded in terms of its actual capability. So the good news is that many of the things that have been in short supply—like are there enough doctors in Africa, enough cultural experts, enough teachers?—AIs can step in and provide those functions. We won’t have the same kind of shortage. So actually figuring out, “Okay, how do we spend our time? How do we have a sense of value? What things do we still want or need to do?” It’s actually not the past paradigm, which is, “Grow enough food, try to stay healthy, try to not get involved in wars.” We’ll almost have an excess of capacity, and that gives us the freedom or uncertainty of, “What will we do with this unbelievable advance?”

ISAACSON: My final question is a little bit lighter. I know what books you love, especially nonfiction books, because you share them on Gates Notes online. I’m wondering about things like movies. Somebody told me you love Spy Game, the Robert Redford and Brad Pitt movie. Do those kinds of movies help your brain relax? What do you look for in movies or art or plays?

GATES: I love movies a lot. Spy Game is a very cleverly crafted story—people don’t realize what Robert Redford’s character is up to, and you actually have to watch it a couple times to understand how carefully that’s put together. I love so many movies. I love plays. My parents took me to Broadway when I was going to school on the East Coast at Harvard. I love music. I play a lot of tennis. So although I probably read more than the average person, including your great books, all those forms of entertainment are both great for learning and great for relaxing.

ISAACSON: Okay, cool, that was a lot of fun. I hope this inspired all the readers here. See you soon.

GATES: Thanks, Walter.

Suit Celine Homme by Hedi Slimane. Shirt Bill’s Own.

———

Grooming: Olga Tarnovestska using Hourglass Cosmetics and Kérastase.

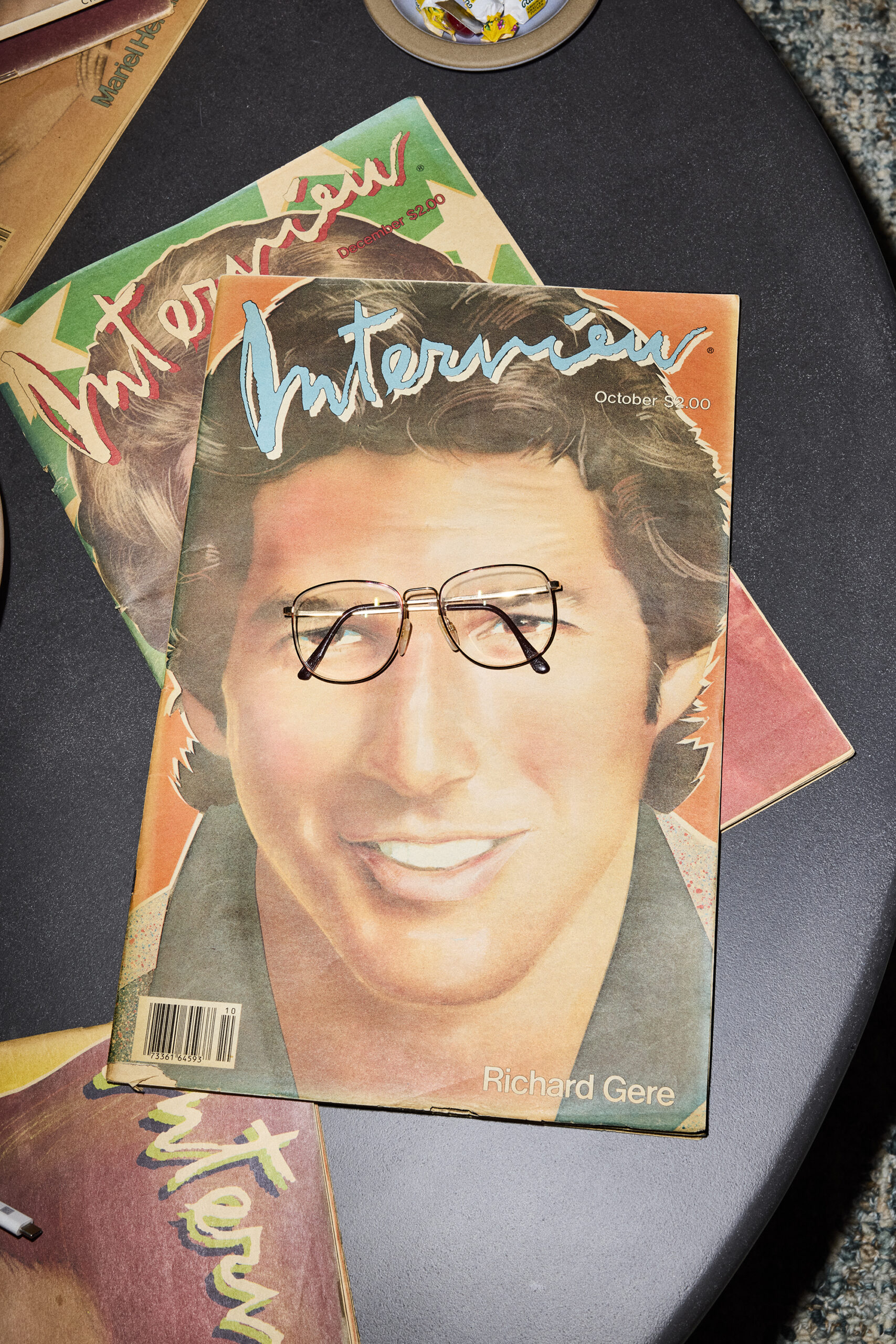

Collage: Whiting Tennis.