When Hayao Miyazaki’s long-awaited and supposed swansong The Boy and the Heron opened at No. 1 at the North American box office last December with a record-breaking $12.8 million tally, it was not only the first original anime title to achieve such a feat, but it was the biggest ever opening for U.S. distributor Gkids. It kickstarted what would be a whirlwind few months for the now 16-year-old company as it took the Studio Ghibli film, (which had opened the Toronto Film Festival in September) to an enormous $46.7 million box office gross (more than double their initial projections) in North America and, later a Best Animation win at the Oscars.

“It was the right film for the right time,” says Gkids president Dave Jesteadt. “The Boy and the Heron was Miyazaki’s first film in 10 years, and I think that a normal concern would have been if audiences had forgotten him, but it was quite the opposite. I think his time away, from The Wind Rises and The Boy and the Heron, coincided with Japanese animation’s stratospheric rise in popularity in America and yet, there was no new Miyazaki film to feed that new audience.”

Gkids founder and CEO Eric Beckman says that across the last few years, “Miyazaki’s legend has grown” thanks to the globalization of content. “There are few people — not just in animation or filmmaking but in any form or medium — that have risen to the ‘godlike’ status that he has. When we first got the film and we were positioning it, we didn’t want to compare Miyazaki to other animators or celebrated filmmakers. If we’re going to compare him to anybody, it’s Michael Jordan, Albert Einstein, Van Gogh or Mozart. I think a lot of people really feel that he’s on of that level of characters that has changed the medium that they work in.”

The Boy and the Heron

Orimedia

But it takes a special — and loyal — kind of company to handle what is touted as Miyazaki’s most personal film to date, and this result is by no means an overnight success, but rather the product of a carefully cultivated near 25-year relationship between the Gkids founders and Ghibli. Japan’s preeminent animation studio has long had a reputation for establishing deep-rooted relationships with partners it trusts, and for Beckman, this relationship predates Gkids when he was running the New York International Children’s Film Festival. There, he programmed films such as Kiki’s Delivery Service in 1999 and curated a Miyazaki retrospective the following year.

The festival, which received more than 3,000 submissions a year and was considered the de facto entry point for a swathe of “amazing animation” that was entering the film space, became the birthplace for Gkids when Beckman noticed there was a huge gap in the marketplace for adult animation that skewed from the usual “four-quadrant family pictures” dominated by Hollywood majors.

“It wasn’t a huge conceptual leap from a film festival that was very mission-driven to a distributor that was very mission-driven,” says Beckman. “The only real shift that happened pretty much immediately was that instead of just being for kids, we shifted to animation for adults very early.”

Since its inception in 2008 with Jesteadt, Gkids has scored 13 Best Animated Feature Oscar nominations and six Golden Globe nominations including Cartoon Saloon’s The Secret of Kells and Wolfwalkers, 2012’s Spanish animated pic Chico & Rita, and Ghibli’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya and When Marnie Was There. “We were filling a market need and it was exciting to bring these films that nobody was distributing in the States and be supported by critics and fans and key theatrical exhibitors,” says Beckman.

The company is in Cannes this year with Directors’ Fortnight title Ghost Cat Anzu, from helmers Yoko Kuno and Nobuhiro Yamashita, a Japanese-French co-production that Gkids exec produced. It’s the third project that the company has exec produced, following The Breadwinner and Wolfwalkers and it’s a role the company will look to expand into in the future. “We’re nimble and boutique and that means that we can be opportunistic — in the positive sense of the word,” says Beckman. “The company has a lot of embedded options for growth, and we will look at those as they come along and as they make sense to us.”

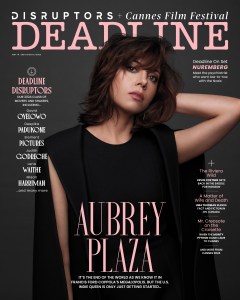

Read the digital edition of Deadline’s Disruptors/Cannes magazine here.

Reflecting on The Boy and the Heron’s success, Beckman is reminded of the first time he saw a rough cut of the film with no dialogue or sound and just English subtitles. “I started crying five minutes in,” he says. “It’s something to be thankful for and joyful for and I think a lot of people who are core fans felt that, so setting it up initially wasn’t that hard — you just had to remind people of what a master he was.”

Both Jesteadt and Beckman credit the audience for “grappling” with one of Miyazaki’s deeper and more philosophical films.

Looking ahead, Beckman believes this is just the beginning of the potential of the genre. “I believe R-rated, $100 million box office animated films are in our future,” he says. “It’s a hugely cross-pollinating, creative period with lots of artistic and commercial potential and I’m very excited. I feel like we’ve entered the beginning of a new era.”