We are speeding north out of Cairo, careering along fast, wide roads through a desert landscape and out into antiquity. After three hours, we reach Rashid, once known as Rosetta, a port city on the Nile delta, and enter Fort Julien, walking clockwise around its interior until we reach the first corner and the reason for our journey.

At this spot in 1799, a discovery was made that would shake the world. Among the rubble of the fort’s foundations, a dark slab of granite-like rock caught the eye of Pierre-François Bouchard, a lieutenant in Napoleon’s invading army. Bouchard had served under Nicolas-Jacques Conté, inventor of the pencil, and he quickly gleaned the significance of the lettering etched into the slab.

This 762kg chunk of granodiorite, recycled from elsewhere into use as a building block, was inscribed with a decree issued in 196 BC on behalf of King Ptolemy V. Although the message is somewhat dull, crucially it was written three times: in hieroglyphs (the beautiful ancient Egyptian pictorial script that could no longer be understood), in demotic (the joined-up lettering used for everyday writing), and in ancient Greek (a known language).

Here, at long, long, long last, was the key to deciphering hieroglyphs, those perfect outlines of people, animals and objects scratched into stone or written on to papyrus millennia ago. The code was finally cracked in 1822 by Jean-François Champollion, who rushed into his brother’s office, shouted “I’ve got it!” then fainted and wasn’t himself for five days. The scale of his achievement can hardly be overstated: thanks to this French philologist, and a few other scholars including Britain’s Thomas Young, 3,000 years of Egyptian history, one of the world’s oldest civilisations, came cascading out into the light.

“This is not just Egyptology,” says Ilona Regulski excitedly, standing by a replica that sits where the stone was discovered. “This is the birth of Egyptology!” It’s an evocative spot, now shaded by the huge spreading branches of a royal poinciana, or flame tree, named for its crimson blossom.

To celebrate the 200th anniversary of this seismic unravelling, a major show about hieroglyphs, curated by Regulski, is about to open at the British Museum in London, where the Rosetta Stone now resides, the British army having taken it off the French when they cut short their campaign in 1801. A globally recognised symbol of all attempts to fathom the mysteries of the past, the stone is the museum’s most visited object – and its most commodified. A huge swathe of the sizeable gift shop is devoted to the stone, its world-shattering hieroglyphs gracing ties, nail files, mint tins and snow globes.

Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt will put this rock star centre stage, with a supporting cast of 240 exhibits including the Enchanted Basin, a granite sarcophagus whose hieroglyphs were believed to have magical powers, giving anyone who bathed in it relief from the torments of love. Along the way, hieroglyphs will provide insights into life in ancient Egypt, from poetry and international treaties to shopping lists and tax returns.

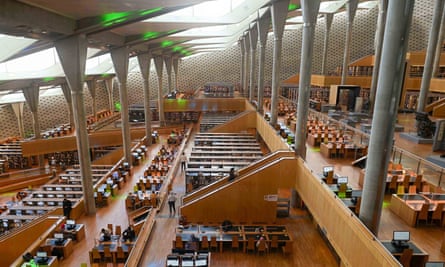

For a further deep dive into Egyptology and hieroglyphs, Regulski is taking a party of British Museum delegates and some journalists on a whirlwind tour of the world the Rosetta Stone sprang from. Our next stop, creating a frisson of excitement on the minibus, is the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, one of the greatest libraries on Earth. Its 2.5m books – there’s room for 8m – are housed in a striking 11-storey structure that looks out over the Mediterranean, its gleaming sides carved with giant hieroglyphs, its glass ceiling angled at 16.5 degrees to make the most of natural light.

“This is the biggest open reading space in the world,” says Ranine Essam, our guide, as we explore inside. You do wonder how anyone manages to pay attention in this extraordinary place. Each of the ceiling windows takes the shape of an eye, with shutters as lashes, all held aloft by columns modelled on closed lotus flowers, and wrapped in a curving concrete shell crafted to absorb sound. The detailing includes black Zimbabwean granite and oxidised Egyptian brass, intended to emulate materials found in ancient tombs.

Essam races us through space after dizzying space, each adorned with paintings and statues ancient and modern, until we reach a huge interactive display. With a wave of her hand, she makes a dark blue coffin appear, spin, then shed its layers: we spiral from inner coffin to cartonnage to wrapping, until the skeleton is revealed – arms crossed, with amulets, earrings and an insert in the mouth to hold it open in readiness for the afterlife.

You can get a taste of the real thing in the British Museum show, which will feature the cartonnage and mummy of Baketenhor, once believed to be a princess, now a resident of Newcastle and its Great North Museum, which has loaned it out. Baketenhor’s inscription, translated by Champollion, is a prayer to several deities for the soul of the deceased.

The show will also dwell on the remarkable story of Ahmed Kamal Pasha, a curator who handwrote almost as a hobby the first dictionary of ancient Egyptian. Its 20 volumes (two are missing) are now being painstakingly restored and preserved in a basement lab in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Essam takes us inside, where teams of young women work in silence at giant tables adorned with scalpels, vials and brushes of all sizes. They are surrounded by 21 large framed posters, each containing four closeups of various bacteria and fungus.

It is astonishing, and refreshing, to see the written word so sanctified, but then the Bibliotheca was built to commemorate the Great Library of Alexandria, one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world, which transformed the city into a great seat of learning, a capital of knowledge. Some estimates number its papyrus scrolls at 400,000, with subjects ranging from maths and astronomy to physics and natural science. It is now lost to antiquity, popularly believed to have perished in a fire although this is only partly the case.

“Now,” says Essam with a laugh as our tour ends. “I have a question for you. What was it like to have Moon Knight filmed at the British Museum?” This is a reference to Disney’s new TV series about the Marvel character who battles frankly terrifying ancient Egyptian gods and monsters, then transforms back into his mild-mannered alter ego, who works at the British Museum gift shop.

Back in Cairo, we head for the French Institute. Napoleon took 2,000 artists on his campaign and the result was the 10-volume Description of Egypt, a publishing endeavour so huge it took more than 20 years to complete. Agnès Macquin, curator of the institute’s library, pulls on a pair of white gloves and talks us through its first edition copy.

“These three snakes,” she says, as we reach the exquisitely detailed animal section, “took two years to engrave.” Well, I think, they do wriggle. “A thousand copies were published in the first edition,” she adds. “But it was so costly only 200 were sold in its first year.” The British Museum’s copy, not in colour like this hefty, ravishing document, will feature in the show.

The next morning, Regulski takes us on a tour of the Egyptian Museum, a handsome pink stone building on Cairo’s Tahrir Square. “This museum really is the mothership,” she says as we pass a golden throne (complete with a footstool decorated with its royal owner’s enemies) and a towering statue that has lost a toe. “I could spend five years just studying this,” sighs Regulski, pausing at a wooden coffin adorned with hieroglyphs, before giving us a thrilling running commentary in the Tutankhamun room.

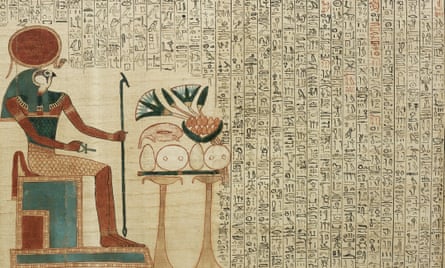

When the boy-king’s treasures were loaned to Britain in 1972, they caused a sensation, with people queueing through the night then making a beeline for his mesmerising blue and gold death mask. “It’s topped with a cobra and a vulture,” says Regulski, “signifying his rule of lower and upper Egypt respectively.” She then points out the hieroglyphs inscribed into the mask’s shoulders, a spell from The Book of the Dead. Rarely displayed, the version of this funeral text that accompanied Queen Nedjmet into the afterlife – richly illustrated on a piece of papyrus more than four metres long and 3,000 years old – will appear in the British Museum exhibition.

“Queen Nedjmet also coordinated the murder of two policemen,” says Regulski. “If revealed on judgment day, these sins would have led to her eternal damnation. But in the papyrus, she appears brave and waits by the scales of justice for her heart to be weighed against Maat, the goddess of truth.”

The anniversary of the decipherment has, inevitably, led to renewed calls for the Rosetta Stone to be repatriated, from both Britain and Egypt. “Talks could start now, in the 200th anniversary year of the decipherment, to send it back and continue its journey,” Joyce Tyldesley, professor of Egyptology at the University of Manchester, told the Sunday Times. In Egypt, Dr Monica Hanna, an Egyptologist leading a repatriation campaign, has talked of “the people demanding their own culture back”. In response, the British Museum points out that there has been “no formal request from the Egyptian government to return the stone”, adding that 28 slabs bearing the decree have been discovered in the country, and 21 remain there.

For a grand finale, we take the minibus to Giza to see the pyramids and the Sphinx, baking in the late-morning sun. Regulski leads us to what’s lurking between the latter’s massive lion paws: the Dream Stele, a commemorative slab bearing hieroglyphs you can no longer get close enough to read. “We have the first copy ever made of this stele,” she says. “It’s super accurate. The stele tells the story of Thutmoses IV, who came here as a young royal to hunt – there were lions and hyenas in those days. He fell asleep and, in a dream, the Sphinx said to him, ‘I will make you king of Egypt, if only you will clear the sand from around my body.’” Thutmoses, who wasn’t next in line to the throne, did as asked and became king, then had this story placed between the paws.

And there it stood in the restless sand for millennia, in plain sight but rendered silent, its meaning lost, like the great library, to antiquity – until the code was cracked and the Sphinx’s voice could be heard again for all eternity.