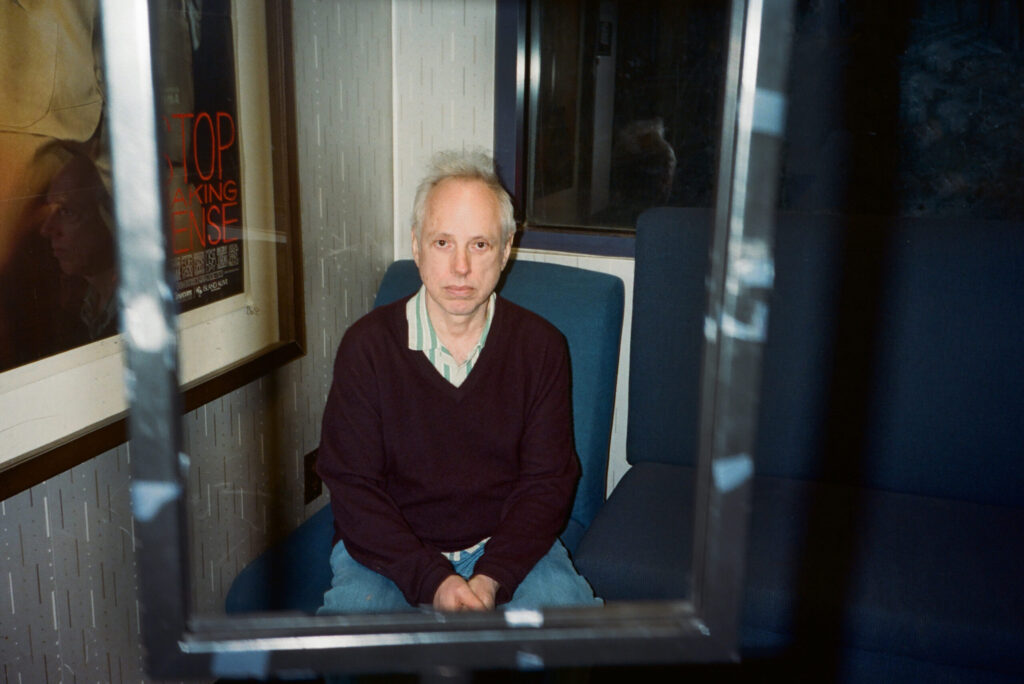

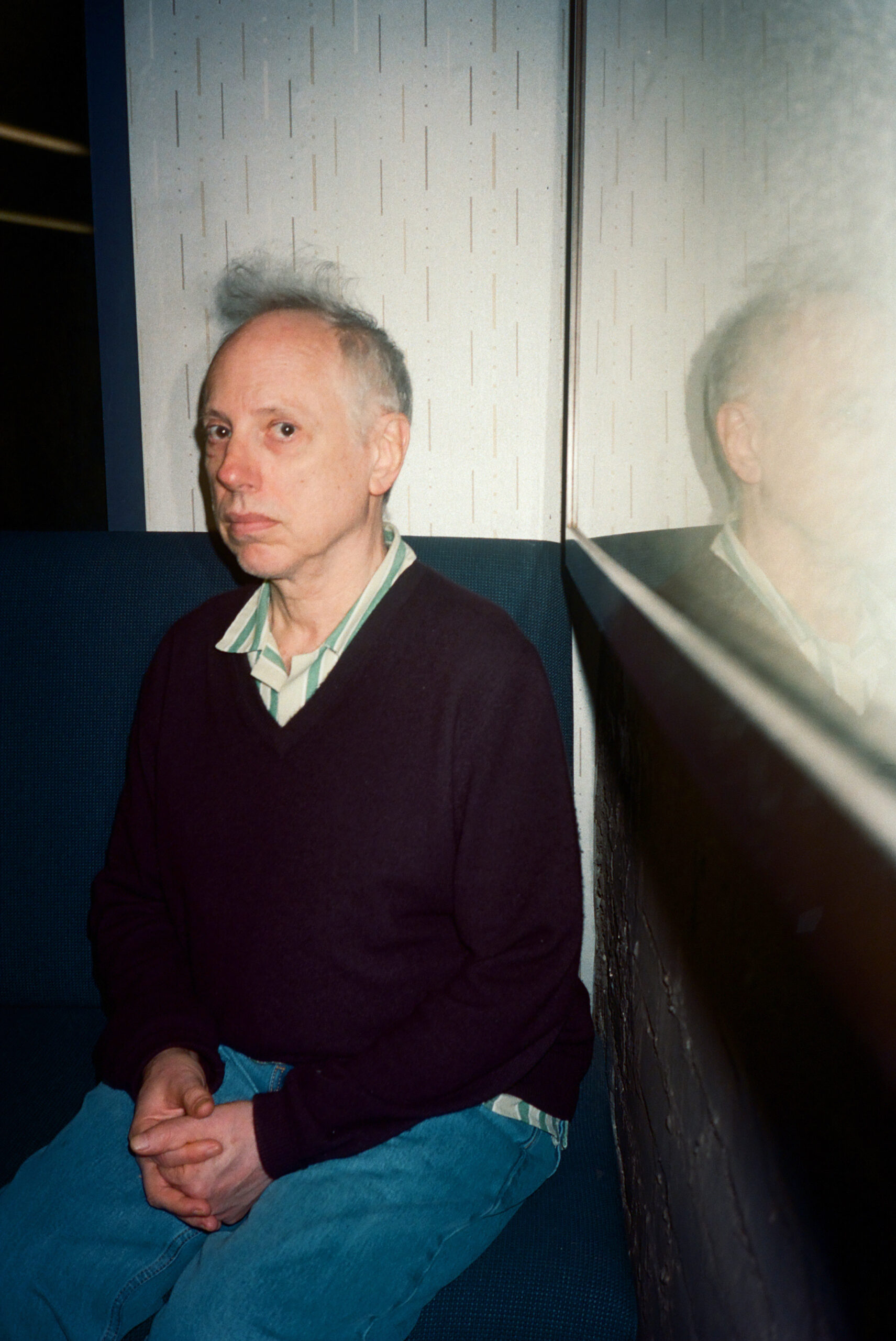

Since his 1989 debut feature, Fear, Anxiety & Depression, the films of Todd Solondz—at once tender, defiant, repellent, and hysterically funny—have served as a kind of litmus test for moviegoers. I myself discovered them as an undergraduate in college (surprise!), where in a course called “Writing About Comedy” I elected to review Happiness, a choice that provoked among classmates a general sense of distaste and bewilderment. Solondz, as critics like to point out, is a student of the human condition, but his findings are not often flattering or affirmative. Over 36 years and eight features, the 65-year-old director has introduced us to characters whose secrets and insecurities compel them to behave monstrously, recasting the halls of a New Jersey middle school or the Ranch style homes of the American suburbs as sites of petulance and perversion. That they remain, still, charming, lovable, and curiously incisive is a testament to Solondz’s unique gifts for tone and characterization, whereby glimmers of hope emerge in these portals of darkness and indecency.

This particular strain of realism, however, has not won Solondz much favor at the box office. Before a recent 20th anniversary screening of his film Palindromes, I asked the director if there’s any comfort in critical embrace. “I wish there were some correlation there,” he said, “but my movies have not been profitable, and if they’re not profitable, it makes it so much more challenging to get movies off the ground.” Solondz last directed one in 2016, and his struggles to acquire financing for Love Child, a project that halted production last summer, have been well-documented. But the director, betraying none of the bitterness of the characters who populate his work, keeps busy at NYU’s graduate film school, where he instructs classes on writing and directing. “There’s no stress when I teach,” he told me. “I just watch young, hopeful, ambitious people—and I’m grateful I’m not one of them.” As restorations of his films arrive at the IFC Center and Metrograph this month, Solondz joined me to talk about the future of independent film and the Hollywood blockbusters that first inspired him to pursue filmmaking as a young man.

———

JAKE NEVINS: Good morning, Todd.

TODD SOLONDZ: Hi there, Jake.

NEVINS: I’d be remiss not to mention that I’m a huge fan of your work. The 4K restoration of Palindromes is exciting news. What’s your relationship to your early work? Do you revisit your films?

SOLONDZ: Oh, no. Personally, I don’t have any interest in watching these movies again, because I spent so much time in the editing room with each of them. So I am always focused on what I’m going to do next.

NEVINS: Then what do you make of the broader reappraisal your work seems to be experiencing? Generally, your films have aged quite well, even if they were polarizing when they first came out.

SOLONDZ: Well, I don’t know. I’m not aware of reappraisals. Maybe there are, but I certainly am very pleased that Visit Films has restored Palindromes so that it will have an afterlife. Otherwise, it might very well have just vanished. So that’s what really pleases me, that new audiences can be found for the movies. I don’t know, it’s hard to know how relevant and meaningful your work remains. I teach at the graduate film school at NYU and I certainly don’t take it for granted that my students are familiar with my work. Some are, but some aren’t. But I do know that it is always a pleasant surprise to see if the movies still resonate with young people today.

NEVINS: How do you like teaching?

SOLONDZ: Oh, it gives me great pleasure. It’s the opposite of filmmaking. Because filmmaking is all stress, and there’s no stress when I teach. I just watch young, hopeful, ambitious people—and I’m grateful I’m not one of them.

NEVINS: Well, I’m curious to hear a little bit more about that. There is a general condescension nowadays toward the viewing habits of younger folks, who don’t see films in theaters so much. Have you drawn any conclusions about their sensibilities from teaching?

SOLONDZ: Well, certainly theatrical film has been on the decline for decades. I don’t know how it even survives at this point. Most of the films young people see are not seen in movie theaters. And film itself is no longer the cultural touchstone it once was. But as I say, that’s been going on for decades, and that even predates the advent of the internet, which accelerated the decline. That said, I don’t pass judgment. I don’t really see any reason to condescend to the ways in which young people take in art and film and so forth. They have different perspectives and experiences. There is no monolithic form in which one can experience these things. Certainly, what lives and thrives on the internet seems to be much closer to the cultural touchstones in the world at large nowadays, and I think one has to accept that and not be too sentimental.

NEVINS: That’s a level-headed perspective. To shift gears a little bit, you were recently profiled in The New Yorker, and in reading that piece I started thinking about a curious dynamic at play when it comes to your work. You’ve often struggled to get financing for your films, but there’s this really strong wellspring of affection for your films among a certain urban or intellectual class. Independent theaters like IFC and Metrograph are screening your films this spring. I’m curious what you make of that.

SOLONDZ: Well, certainly I’d trade all of the compliments for a budget to make another movie. [Laughs]

NEVINS: Right.

SOLONDZ: I wish there were some correlation there, but my movies have not been profitable, and if they’re not profitable, living in a market economy as our cinema does, it makes it so much more challenging to get movies off the ground. People are still working on trying to get one of my projects off the ground, and I always have to be engaged in some projects, otherwise I would succumb to all sorts of depression. So I’m always involved, even if it’s not a film project. And teaching is a full-time job; it’s a nice accessory to my routine, and I do enjoy spending time with young people.

NEVINS: Let’s talk about Palindromes a bit. Around the time of its release 20 years ago, you spoke to the great Sigrid Nunez about how some of the reception to the film was overwhelmed by the matter of abortion: what your stance on it was, and whether or not the film was pro-choice or pro-life, et cetera. It struck me that there might be an even more intense reaction to it nowadays, since people seem to probe any and all art for indications of its politics. Do you have a hunch as to how a film like Palindromes might sit in the cultural firmament today?

SOLONDZ: I never know how people will respond. I never second-guess, but I think Palindromes came out about the same time as Vera Drake, Mike Leigh’s movie about an abortionist. It was a hagiographic film about a woman who is courageous enough to perform abortions illegally and doesn’t even charge people for her good work. And as much as I am an admirer of Mike Leigh, I am not interested in creating work that reinforces beliefs that audiences already hold dearly. I think I’m much more drawn to certain kinds of contradictions and challenges, to the way in which we take in these irresolvable issues, because abortion is irresolvable. When the movie was made, the country was very divided. And we had thought that the presidency at the time was so extremist; we thought that was a pinnacle of where America could go. And I think that underscores the innocence of that time. The world is a very different place now. We come in with our own prejudices and preconceptions, and one hopes one leaves not so much with the discovery of a character evolving as much as with an audience’s perception evolving—that your experience of the film evolves and you come out of it questioning some of the ways in which you may have looked at things before the movie started.

NEVINS: Well, Palindromes certainly forces the viewer to have a more expansive idea of character, since you cast eight different actors in the role of Aviva. Talk to me about your decision to try out a formal experiment like that. Obviously, it’s a risk.

SOLONDZ: Yes, of course. It was a risk. It was a conceit that took a certain amount of courage. But it was at a time when I was very excited about playing with different formal strategies, if you want to call it that. I had a certain amount of freedom and stock in my career that I wanted to take advantage of. And when I think about where this initial idea of recasting actors or different actors playing the same role comes from, it’s certainly a familiar enough ploy in theater and television. I remember very much being affected when I was a child and there was a television show called Julia, with Diahann Carroll. There was a character on the show played by an actress, and three weeks into the run of the show she was murdered in real life, so the subsequent episodes had to be played by another actress. And when I watched the show, none of the other characters responded in any way as if they noticed anything different about a new person playing this character. And yet, that was all I could think about as I watched the show—how this erasure could happen so seamlessly. I think that that sat in the back of my head for many years and may be where all of this came from.

NEVINS: Oh, that’s so interesting. I hadn’t known that. You once said that it was after Palindromes that you realized you weren’t a “Hollywood filmmaker.” What did you mean by that? What about your experience with that film led you to understand yourself as outside of the system, so to speak?

SOLONDZ: Well, I grew up watching popular movies. As a child, really up until I went to college, they were movies that were PG and milder than PG. My family didn’t want me to see anything as troubling as an R-rated movie. And yet, when I did go to college—and it was a great time to go to college, because movies were projected and every night you could see [Jean-Luc] Godard followed by Groucho [Marx] followed by Howard Hawks—that’s where I immersed myself in moviegoing. And I may not have understood many of the movies I was watching, but I took them all in. I was very much in love with so many Hollywood movies that it seemed like that would be where I would strive to find myself. When I write my screenplays, they are very conventional—not in subject matter so much, but they’re very linear. There are no ellipses and flash forwards or the kinds of Godardian hijinx that other arthouse filmmakers employ. They’re written as such that even an 11-year-old could follow them.

NEVINS: Right.

SOLONDZ: And I wanted it to be that way, because I knew I was dealing with troubling subjects, delicate subject matter, and I didn’t want that form to get in the way. And yet I found myself playing with form; I didn’t anticipate that. I thought that somehow these movies would be Hollywood movies, but Hollywood also changed. And it was after Palindromes that I did have this reckoning where I realized, “No, there is not really a place for me in that system,” and that I would have to struggle to make movies outside of it. Notwithstanding Storytelling, the first studio movie with a big red box in it.

NEVINS: Right. Although, the Europeans didn’t get the red box, did they?

SOLONDZ: They missed out!

NEVINS: On this subject, a $6 million movie called Anora just won Best Picture. Its director Sean Baker went on stage to tout the importance of the theatrical viewing experience. That a movie like that could scale such heights is being received as a triumph for independent film. I’m curious what you make of it.

SOLONDZ: From what I’ve read, I think that a lot of the composition of The Academy—of which I am not a member, and I don’t expect to be invited to be a member either—has changed in recent years. So a movie like Anora, like Moonlight or even Nomadland, are much more in play than they would ever have been in the past. Not that I follow figures, which I don’t imagine are really so robust for any of these movies, but the box office is what matters in Hollywood. What matters is how much you make—how much a movie profits—and everything else is immaterial. So it’s nice if the director was encouraging people to go to the movies, but we’re living in a different world. It’s a niche audience that relishes going to the movies, and it’s very hard to compete when you have home entertainment that is cheaper and just makes it easier to access all sorts of movies than going out and troubling yourself to get in the car and park and find a babysitter and so forth. That’s just the reality of the world we live in, for better or for worse. I mean, on the plus side, you have access to movies that you’d have to wait maybe years before they would return for a brief run at Film Forum or some sort of revival house like that. And now, with just a few clicks, you can see anything you want.

NEVINS: Have you had any recent movie theater experiences that were memorable?

SOLONDZ: I very much enjoyed Catherine Breillat’s movie Last Summer. I enjoyed Owen Kline’s Funny Pages. And I enjoyed watching Jeremy Strong and Sebastian Stan in The Apprentice.

NEVINS: That was a terrific movie, but it was struggling to find distribution.

SOLONDZ: Well, it did find it, though. I’m afraid I have not yet seen Anora, though I want to. I’m just slow and I don’t go out very much, period. But I do want very much to see Anora.

NEVINS: I’d be curious to know what you think of it. I’ve got one last question for you. It struck me in preparing for this movie that a lot of the rhetoric about you and your filmmaking concerns your personal feelings about the human condition, as if you’re some kind of oracle. People want to know if Todd Solondz is optimistic for humanity, or if we’re doomed. What do you make of those questions and the almost binary terms in which your films are received?

SOLONDZ: I don’t know that anyone sees me as an oracle; certainly my kids do not. They would mock me for such a presumption. But look, we are living in difficult or very radically different times from the world I grew up with. It’s a challenge for many people to be optimistic with the way the world is being reshaped. We live in the most powerful country in the world, so therefore what we do affects the rest of the world. And that’s a responsibility that we have to live with and accept. I mean, you’re right, there are times where it is wise to be pessimistic and foolish to be optimistic and vice versa. The only common denominator I can see among people who respond [to my work] is an open-minded sensibility. And that’s the best way to engage with what I do.

NEVINS: Well, your films have meant a lot to me, and I appreciate you taking the time today.

SOLONDZ: This was a pleasure. Nice to meet you.

Content shared from www.interviewmagazine.com.