The stage is dimly lit. Through the gloom, a figure emerges, muttering incomprehensibly. From a distance, the figure vaguely resembles Kurt Cobain – ragged clothes, dyed dirty-blond hair – a resemblance that increases when they climb a staircase into the stage’s representation of a battered-looking apartment, and put on what looks remarkably like a pair of the white-framed women’s sunglasses so associated with the late Nirvana frontman they’re now colloquially known as “Kurt shades”. A man enters stage right, noisily dragging a leaf rake behind him, and starts singing in a powerful bass voice. This is not a development that goes down well with the figure that looks like Cobain, who hides in a kitchen cupboard.

This is a rehearsal for Last Days, the Royal Opera House production based on Gus Van Sant’s 2005 film about a disaffected rock star called Blake: it was fairly obviously a grim fantasy based on the “missing” five days between Cobain absconding from a rehab facility in Los Angeles and killing himself in an outbuilding of his Seattle home, a period during which his wife, Courtney Love was reduced to hiring a private detective to try to find out where he was.

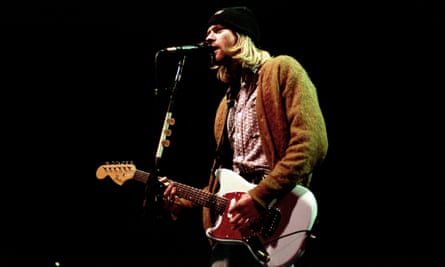

It’s an intriguing idea. On the one hand, if you were looking to stage a production that might have an appeal beyond the usual audience intrigued by a modern opera (and it’s worth noting that Last Days features an aria sung by acclaimed “alternative pop” singer-songwriter Caroline Polachek, formerly of indie band Chairlift) then Cobain would seem like ideal subject matter: he is both a doomed, flawed tragic hero and unequivocally the most iconic figure that rock music has produced in the last 30 years.

On the other, if you were looking for a film to adapt as a theatrical production, Last Days seems a deeply unlikely choice. It has no real linear plot (“having a literal ‘I know what happened to Kurt Cobain in his last days’, we’re not going to do that,” says co-director Anna Morrissey) and what dialogue there is is both improvised and pretty desultory. When the opera’s authors, composer Oliver Leith and librettist, art director and co-director Matt Copson contacted Gus Van Sant to ask his permission for the adaptation, they also asked if he could forward them a copy of the film’s script. “He sent back a Word document that was one page,” says Copson. “It’s like four red words: sofa, insurance document, something else. But it was lovely, because he also just said, ‘Do your own thing.’”

It’s advice the team behind the opera clearly took to heart: certainly, no one is going to claim Last Days as a wilful lunge for lowest common-denominator mainstream appeal. Here, thanks to gender-blind casting, Blake is played by a female actor – Agathe Rousselle, best-known as the lead in Julia Ducournau’s Palme d’Or-winning horror film Titane. What little dialogue the character had in the film has vanished: Blake neither sings nor speaks, communicating entirely in the kind of muttering I heard at the rehearsal, although Copson points out: “Those mumbles are surtitled and they give us hints of things throughout.”

Liberties have been taken with the plot as well, to include what Copson calls “literal magic realism”. And the character of Blake’s manager – portrayed in Gus Van Sant’s film by Kim Gordon, the former bassist in Sonic Youth and a friend of Cobain – is played by a Montana-based cattle auctioneer, chanting in the profession’s famous hyperspeed monotone. “He was 17 years old and he didn’t know who Kurt Cobain was, which was very funny,” says Leith, who recorded him for the opera. “He was like, ‘This isn’t an evil opera thing, is it?’ I was like, ‘Well, we don’t know yet.’”

Neither Copson, best-known as a visual artist, nor Leith, a classical and electronic composer whose work has been released by Matthew Herbert’s Accidental label, has ever worked on an opera before: they began writing Last Days during the pandemic, although they’re dismissive of the idea that lockdown might have chimed with the film’s theme of isolation. As Copson points out, in the film, Blake actively wants to be alone, but is continually interrupted by everyone from door-to-door salesmen to his record company.

Instead, Oliver says he was drawn to Van Sant’s film partly because of its sound design, in which even the most mundane noises – the rustling of leaves, the creak of a chair – are “raised up” to the same volume as the actors’ voices. It chimes with his own interest in “raising everyday stakes, framing boring stuff as, I don’t know, sublime”. His 2018 piece good day good day bad day bad day dealt with daily routines; Honey Siren, for which he won a 2020 Ivor Novello award, was based on the ubiquitous urban sound of a siren rushing past.

“Rather than just raising it, as the film does, here it is tuned and utilised,” he says. “The birds actually sing songs, wolves howl but they’re singing in tune. And cereal bowls are a big theme. When someone pours cereal, it’s unnaturally loud and musical. It acts like a zoom on a film. You’re suddenly like, ‘OK, that’s what I’m looking at, that’s what I’m focusing on.’”

For Copson, the draw was the film’s combination of “banality and magic” and the figure of Cobain himself, his continued relevance 28 years after his death. “I think what makes it interesting and, most importantly, what makes it interesting in 2022 – which is very different even to when the film was made – is the relevance and prevalence of this archetype that seems, to me at least, to say something about the contemporary condition we all find ourselves in. You speak to any young person – everyone is on display to a degree that they weren’t before, and there are questions of privacy that come up all the time. The essential idea of, ‘Am I an individual or am I member of society? Can I freely express myself or can I not? What does it even mean to express yourself? What is freedom?’

“I think the reason why this archetype, this Kurt figure, remains relevant is because he so heavily demonstrated that paradox. He held so many contradictions within himself. His suicide note says, ‘I love people too much’, then it says, ‘I hate people.’ He’s like a walking paradox, and I think those are really important and beautiful figures for us to grapple with, because it’s an extremity of what I personally feel all the time.”

For all its evident strangeness, its mumbled dialogue and lack of a plot, all three are keen for Last Days to reach a broader audience in a world where opera is seen as a forbidding art form. “Productions are alienating,” says Oliver. “New operas are mostly just about issues, and that’s the dullest thing – that’s the climate change opera, that’s whatever. It’s too simplistic.”

“I think it should resonate,” says Morrissey of Last Days. “You should feel something. You should feel really moved. I don’t think consensus and agreement is a thing we want en masse, but rather individual understanding or resonance with yourself.”

“I think we’re united on one front,” says Copson. “We’re all like, ‘We just want people to feel and then they’ll gradually find it accessible as a form.’ And that doesn’t mean dumbing it down.”