Shared from www.theguardian.com.

My earliest reading memory

The first books I remember reading were from the public library in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where my family came as refugees from Vietnam in 1975. I vividly recall Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, which I read at six years of age, but unlike most children, I didn’t like it. The story of a boy who flees home on a boat and finds himself among foreign creatures was too dark for me. Perhaps it was too close to reality.

My favourite book growing up

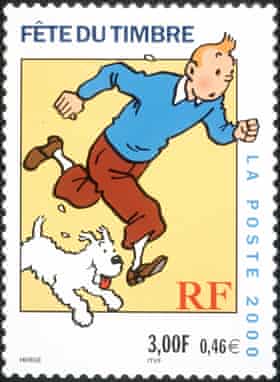

The Tintin series by Hergé. The books were so beautifully drawn and told, with memorable characters and adventures in exotic lands. The stories were captivating.I loved the exoticism but didn’t notice the racism and colonialism. I’ve given the books to my eight-year-old son and he loves them, too, but I make sure we discuss the problems.

The book that changed me as a teenager

At 13 or 14, I read Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. I sensed a similarity between my Vietnamese refugee world and Roth’s Jewish American world, but what really struck me was the moment when adolescent Alex Portnoy masturbates with a slab of liver. On finishing his dastardly deed, he puts the liver back in the fridge and his unsuspecting family dines on it that evening. I paid tribute to the scene in my novel The Sympathizer. Let’s just say a poor squid is involved.

The writer who changed my mind

At 18, I came across Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. I was so enraptured that I finished it in a couple of days. I didn’t know that Asian American literature existed before reading this book, but eventually I would write my own book on it, which dates to the late 19th century. Discovering Asian American literature changed my life and my mind.

The book that made me want to be a writer

The monkey in Curious George was a childhood favourite. It must have made me want to be a writer, because the first book I created, in the third grade, was an animal story. Lester the Cat, which I wrote and drew, was about an urban cat stricken with ennui who flees to the countryside, where he falls in love with a country cat.

The book or author I came back to

In my early teen years, I read Larry Heinemann’s novel Close Quarters, about the war in Vietnam. Average American soldiers turn into murderers and rapists. The most memorable Vietnamese character is a prostitute named Claymore Face. I was horrified by how Vietnamese people were depicted, and hated the novel for a long time. On rereading it as an adult and a writer, I understood Heinemann was right. His obligation was not to editorialise, sentimentalise or humanise the Vietnamese, when American soldiers dehumanised them. His obligation was to make his readers uncomfortable, because that’s the least they can feel when reading about war.

The book I reread

Voltaire’s Candide was, for some reason, in the children’s section of the library. I thought it was a pretty fun fable. As an adult, I realised that the comic travails of Candide were a good model for what I was putting my narrator of The Sympathizer through, so I put in some Candide-like misadventures in its sequel, The Committed.

The book I could never read again

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. I enjoyed it in high school, but the prose didn’t attract me when I looked at it a few years ago. This was probably because I was obsessed with the next book here …

The book I discovered later in life

António Lobo Antunes’s The Land at the End of the World, inspired by the author’s war experience in Portugal’s colony of Angola. The prose is dense, imagistic, profane and beautiful, the opposite of Orwell’s injunction, in his essay Politics and the English Language, to write clearly.

The book I am currently reading

Garrett Hongo’s The Perfect Sound: A Memoir in Stereo, about his audiophilic obsession, his life, and his poetic voice. Hongo has been my mentor in buying fancy stereo equipment. He’s cost me a small fortune.

Images and Article from www.theguardian.com