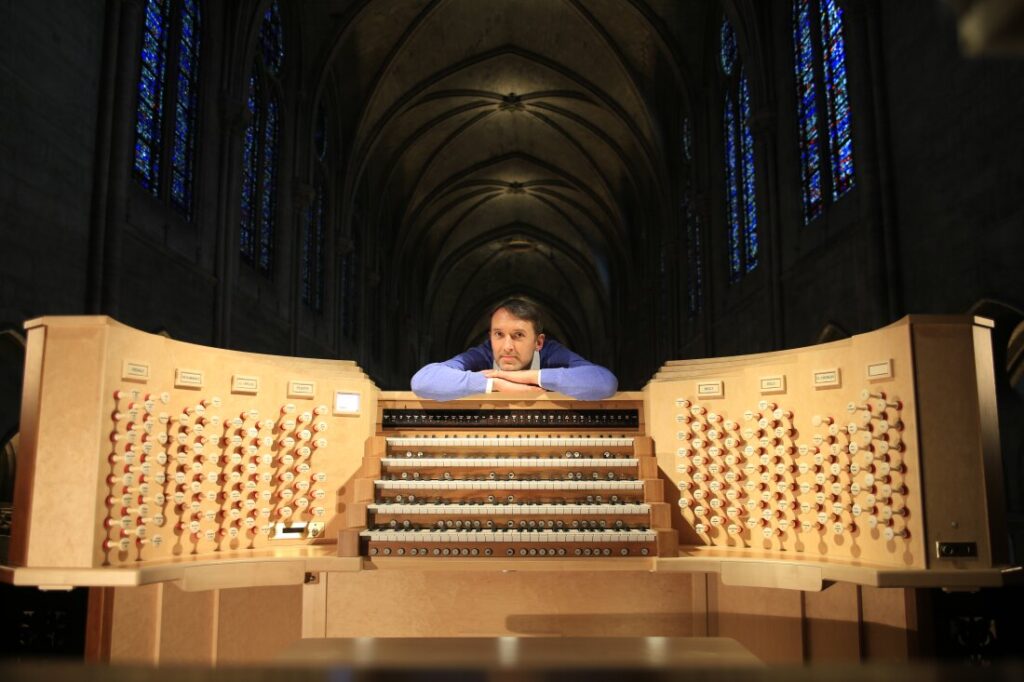

Olivier Latry, Notre Dame’s longest-serving organist, poses beside the refurbished instrument, ready for the reopening ceremonies after the destructive fire in 2019.

Philippe Guyonnet/Notre Dame Cathedral

hide caption

toggle caption

Philippe Guyonnet/Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre Dame Cathedral reopens this weekend, after painstaking reconstruction by more than 1,200 artisans who worked to restore the 12th century landmark following the great fire of April 2019. Some 50 world leaders and heads of state will attend two days of ceremonies showcasing the cathedral’s art, history and religious rituals. The cathedral’s grand organ, with some 8,000 pipes, will play a leading role.

Olivier Latry was the last person to play Notre Dame’s great instrument, on Palm Sunday 2019, the day before the fire. Latry is the cathedral’s longest-serving organist, and when the position opened up he applied for it on a lark. “I was young and totally not nervous to go there,” Latry says, sitting in a Paris café a couple of days before the reopening. “Because I thought it’s not for me. It’s just a nice experience and that’s it.” But he landed the job — and that was 40 years ago.

Like many, Latry remembers the moment he found out about the fire. He had just arrived in Vienna for a concert tour when he received a text that Notre Dame was burning. “Of course, I thought it would collapse — the organ and everything.” Latry and his wife flew back to Paris the next day. Emerging from the metro in front of the church, he was afraid to look up. But it was a beautiful spring day and a tree in full bloom hid most of the damage.

“The only thing that we could see was just the two towers illuminated by the sun,” Latry recalls. “They were so white because they received so much water from the firemen. We couldn’t imagine that something could happen to Notre Dame. It was like Notre Dame was saying to us, ‘I was there 850 years ago. I will be there in a thousand years.’ “

The first organs were installed in the famed cathedral in the 14th century. By 1730, a brand new “Grand Organ” was commissioned, and over the centuries it has been updated, added to and reworked. Some of the organ’s current pipes date back to the 1400s, according to Christian Lutz, a master organ builder, who explained some of the current restoration to President Emmanuel Macron on French television. The instrument is three stories tall. And it sits right near the hole left in the roof when the spire collapsed.

“I’ll never forget the joy we felt when we discovered that the Grand Organ was intact,” Lutz recalled. “It was filled with lead dust, but it had not burned. It didn’t melt in the heat and the firemen had not inundated it with water — they knew what they were doing.”

The organ was dismantled piece by piece, removed from the cathedral, cleaned and refurbished. The most complex phase came when they reinstalled the instrument and had to harmonize it within a noisy worksite. Each pipe is fine-tuned in relation to the neighboring pipes. You need absolute silence, Lutz said. So for six months they worked in the cathedral overnight.

Latry took part in those late-night sessions. “An organ, especially an organ like Notre Dame’s, has the soul of all the organ builders who worked in it,” he says. “And I think it’s important to try to collaborate because the organ builders are already a part of the interpretation of the pieces that we’ll play afterwards.”

Olivier Latry, standing near Notre Dame in Paris, is the cathedral’s longest-serving organist. He’ll take part on the reopening ceremonies, beginning Dec. 7.

Notre Dame Cathedral

hide caption

toggle caption

Notre Dame Cathedral

Last month, Latry was able to play the organ after the scaffolding inside the cathedral was taken down. He says the instrument is just as it was before, but the acoustics are transformed. The sound reverberates a full eight seconds. “Because the stone is so clean, there is no dust,” he explains. “And we can hear a kind of big wave [of sound] going to the end of the church.”

The instrument, he says, is a sound mirror of the cathedral’s architecture, and a key part of its liturgy. A special organ blessing and “wake up” ritual for the organ is slated for Saturday evening. “This ‘wake up’ of the organ is something really incredible,” Latry notes. “Eight times the archbishop will call to the instrument. The first one, for example will be, ‘Organ, holy instrument get up! Awake!’ ” A different command is called eight times. The organist must answer, always improvising to match the emotion of the moment.

“Each time we have to find the right music to comment on the words,” Latry adds. “It lasts ten minutes, but it’s an incredible moment.” This is the true mission of an organist, he says — to be the voice and soul of the cathedral.

The digital version of this story was produced by Tom Huizenga and edited by Lars Gotrich.