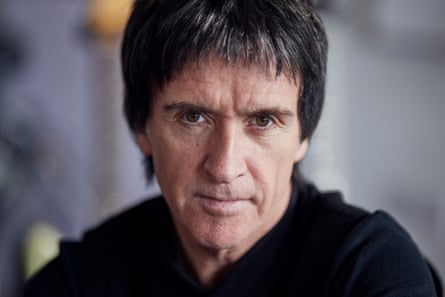

‘Can you just move that Ricky?” says Johnny Marr, gesturing towards the jetglo Rickenbacker 330 guitar resting on the stand next to me, as we rearrange the room for a photoshoot. This Rickenbacker? The one I’ve heard several thousand times on various songs by the Smiths? The one Marr used to write the music for Still Ill and What Difference Does It Make? The Rickenbacker pictured lying on a studio floor on the sleeve of Oasis’s debut single, Supersonic? That Ricky? “Yeah,” he says. “Can you just bring it over here?” I begin to move. It’s only a few steps but I’ve rarely taken more care. It’s like Van Gogh asking you to pass him his favourite paintbrush.

We’re in Marr’s studio in Stockport and he is standing in the centre of a semicircle of guitars which will be instantly familiar to many of his fans. Wherever you look, in fact, there is an important musical artefact. Slightly incongruously there is also a drum kit in the corner, but he’s quick to distance himself from it. “That thing is not mine,” he says. “I’ve probably sat behind a drum kit three times in my life. It just looks totally wrong.”

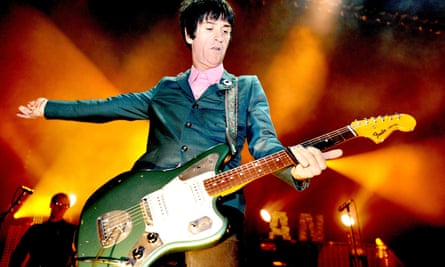

Indeed, it is difficult to think of Marr playing anything other than guitar, the instrument he fell in love with aged five after seeing a toy version in a Manchester shop window. He finally got his own two years later and has been “obsessed” ever since. That obsession carried him into various bands from the age of 13, including the Smiths, the group he co-founded when he was just 19. Over the course of five wildly productive years, the Smiths recorded four still adored albums and a string of singles, before Marr left, unsettled and unsatisfied, to forge a career as something of a travelling guitarslinger.

He joined his old mate Matt Johnson in the The for two albums; formed a duo, Electronic, with New Order’s Bernard Sumner; and later joined the Cribs and Modest Mouse. He has also released four solo albums since 2013, the best bits of which feature on a new compilation, Spirit Power, out next month. All this before you even get to his work with Chrissie Hynde and Kirsty MacColl, or his collaborations with film soundtrack maestro Hans Zimmer, which include a Bond theme with Billie Eilish and a Spider-Man score with Pharrell Williams.

And it’s not just studio work. Only a few weeks ago, Marr says, he was moonlighting with PJ Harvey at her Manchester show, joining her on stage to perform three songs. “We’ve been friends for about five or six years,” he explains. “I love all of her work but the last few albums are fantastic. She’s in a class of her own. I’d definitely work with her again if the opportunity came up.”

Marr is playing two mighty career-retrospective shows at the same venue – the recently opened Factory International – in December. Surely it’s the perfect time to get Sumner on stage for the Electronic reunion so many fans have been waiting for? “I haven’t thought about any guests,” he says, “although it’s been mentioned. I’ve been too busy working out the arrangements”

The studio we’re in today, a large unit in a converted mill, has served as the centre of Marr operations for writing, rehearsing and recording since 2015. It’s not always quite like this in here, though, the more significant members of his guitar collection not usually being gathered in one place. But it’s been like a museum of late while he’s been finalising Marr’s Guitars, a coffee-table book featuring photographs of his jaw-dropping collection. The book features 53 instruments in all, with 30 or so not making the cut.

The idea for the book was something he’d carried around with him for several years, after seeing his friend and regular collaborator Pat Graham’s abstract portraits in his 2011 book Instrument. “Pat had taken some photos of Jerry Dammers’ keyboard and made it look like a weird landscape,” Marr says. “Another I loved was of the pickup on [Fugazi frontman] Ian MacKaye’s Gibson SG, which I thought looked like an oil refinery in Iceland – it was so beautiful.”

So creating a visually arresting, high-quality art book became Marr’s main aim, and he approached it with the tenacity and enthusiasm he would normally bring to a new album. “I wanted it to be in the houses of people who wouldn’t normally have guitar books,” he says, recalling visiting the homes of his middle-class friends as a kid. The more aspirational parents might have coffee-table books of Mercedes, Porsches, zen gardens or architecture out on display. “My dream is for more regular people to have a book on guitars because it’s a beautiful thing. Then the stories about me come secondary.”

He also didn’t want it be like other books on prized guitars, which remind him of “watch catalogues”. There had to be grit, with the guitars photographed in their natural environments, not polished up and displayed in a sterile showroom. So he and Graham, along with Marr’s technical guitar assistant Rich Henry, and longtime art director Mat Bancroft, got to work planning, shooting and even documenting serial numbers.

There’s also an interview conducted by Martin Kelly, who co-authored the definitive book on Rickenbacker guitars (a revised edition of which was published last month). And next to each guitar is the instrument’s story. The tales are enlightening, and Marr hopes they will form the definitive account – a line under everything. It’s also revealing just how many guitars Marr has either given or leant to other musicians.

There is a beautiful 12-string sunburst Gibson 335, which you can see in the video for Sheila Take a Bow, that Marr subsequently gave to former Suede guitarist and successful producer Bernard Butler. And there is the 1960 Gibson Les Paul that he gave to a certain struggling musician called Noel Gallagher, only for the Oasis guitarist to smash it while dealing with a stage invader in Newcastle. Gallagher then called Marr to ask for a replacement and duly received a black 1978 Gibson Les Paul Custom.

“It’s just to be nice,” says Marr. “As simple as that. Bernard is a good friend and I knew he’d love that guitar. And me giving Noel those guitars has become such a big story over the years, but people don’t realise that at the time he wasn’t who he is now. He was just a kid from Burnage. I had no idea Oasis were going to go on to such big things. I did it because he was in need, because I was lucky and had lots of guitars, and because I wished someone had done it for me.”

But given that Gallagher smashed an instrument that not only features on the Smiths album The Queen Is Dead but was also formerly owned by Pete Townshend, why did Marr then give him another expensive instrument? “I must confess it’s why I quit drinking,” he says, perhaps only half-joking, although he has now been teetotal for nearly 30 years. “I wasn’t drunk, but the chances are I was very hungover when I agreed to that.”

Marr says putting together the guitar book has stirred the kind of feelings he was expecting when writing his 2016 autobiography Set the Boy Free but which never came. He says it’s not catharsis, as such, but a recognition of the life he has lived. “I think there’s something about how important the guitars are to me, and remembering how I felt the day I recorded Nowhere Fast, say, and thinking about who I was at that time. It’s a good feeling, absolutely, but with a certain poignancy. I’m at a point in my life and time has passed. I’m not just talking about the Smiths here, which is people’s immediate assumption. I’m thinking about that, but all the other things I’ve done too. It’s perspective – and if I allow myself the luxury to reflect on what I’ve achieved, it is mind-boggling.”

One person close to his thoughts has been Andy Rourke, his schoolfriend and former Smiths bandmate, who died in May. Marr says they’d seen a lot of each other in the past 10 years and that their families spent last Christmas together. “Andy was around while I was working on the book,” he says. “He was a pretty discerning person so I wanted him to be impressed. I’ve got a nice picture of him looking over the book in the hospital when the layout was being done. He liked that there is a picture of the two of us in it. I think about him a lot – and he thought the book was great.”