In these days of extreme political polarization, one longs for signs of unity and humanity, even if we have to reach back nearly 40 years in the wayback machine to find it.

Filmmaker Bao Nguyen was only two years old, in 1985, when more than 40 of America’s biggest music stars slipped into A&M Studios in Hollywood during the wee hours following the American Music Awards. Their mission? To record a song called “We Are the World” that would raise money and attention for famine relief in Africa. The names involved were stunning: from industry icons Ray Charles, Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan, to an ascendant Bruce Springsteen, and hot newcomers Cyndi Lauper and Huey Lewis. The project was the brainchild of Harry Belafonte, and executed by the A++ team of Quincy Jones, Lionel Richie, Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder.

Producer Julia Nottingham and director Bao Nguyen attend the L.A. premiere of ‘The Greatest Night in Pop‘ January 29, 2024.

Leon Bennett/Getty Images

During the thick of the pandemic, director Nguyen and his producing partner, Julia Nottingham, (who was three on that historic day) began pre-production on The Greatest Night in Pop — a 96-minute, fly-on-the-wall look at what went down behind the ivy-covered walls at the corner of Sunset and LaBrea on January 28, 1985. Featuring new interviews and archival footage from the original four-camera shoot — including material unearthed from the trunk of a staffer’s car and audio culled from the tape recorder of a Life magazine reporter — Nguyen weaves together a tale teeming with emotion, tension, purpose, humor, charm and grit. Although most of the artists come off well in the documentary, the real hero is Lionel Richie. After hosting the American Music Awards earlier in the evening, where he also performed and won six awards, Richie presided over the proceedings at A&M like a seasoned diplomat, deftly navigated the issues and insecurities of nearly four dozen superstars, and kept the entire recording process from imploding.

Producer Quincy Jones famously hung a hand-written sign over the entryway that read, “Check your ego at the door,” but the dynamics in the room proved to be more complicated than that.

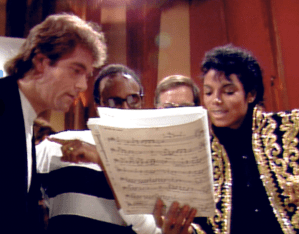

Michael Jackson and Bob Dylan during the recording of ‘We Are the World’

Netflix

In this documentary — which made its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, and debuted a week later on Netflix to coincide with the single’s 39th anniversary — we discover why Prince and Madonna weren’t present, and why Waylon Jennings made a hasty exit halfway through the night. And in lighter moments, we see Stevie Wonder “teaching” Bob Dylan how to sing like Bob Dylan, and Wonder again with Ray Charles, as the pair amiably walk each other to the men’s room — the blind literally leading the blind. Each revelation in the film is a gem, a rare “Stars — They’re Just Like Us” moment decades before reality shows and TMI pulled the curtain back on celebrity vulnerabilities.

On March 7, 1985, a scant two months after “We Are the World” was recorded, the song was released simultaneously around the globe to huge fanfare. In the 39 years since, it has raised more than $63 million for USA for Africa.

Deadline recently spoke separately with Nguyen and Richie about their Emmy-contending documentary.

Huey Lewis and Michael Jackson at the recording of ‘We Are the World.’ Quincy Jones can be seen behind the sheet music.

Netflix

DEADLINE: Why did you decide to make The Greatest Night in Pop?

BAO NGUYEN: Because I was only two years old when the song was recorded, I was like, “Am I the right person to tell this story?” But it actually took a trip to Vietnam when I was visiting my family, and I got into a taxi cab, and it was a 60, 70-year-old Vietnamese taxi cab driver who spoke no English. He put on a mix CD, and the first song that played was “We Are the World.” And so that was the serendipity I needed to tell me that I needed to make this film.

DEADLINE: Why was it important to shoot new interviews for the documentary at A&M Studios (now Henson Studios), in the very room where the song was recorded?

NGUYEN: The recording took place almost 40 years ago. To have someone try to remember something that happened 40 years ago — I can hardly remember what happened last week! So whatever I could do to help people conjure up those memories is important. But also, it was important to pay reverence to the spirit of what happened on that night in that room. So 95 percent of the interviews were shot in the actual room where it happened.

Lionel Richie interviewed in the room where he recorded ‘We Are the World’

Netflix

DEADLINE: Lionel, what do you remember from being in the room that night?

LIONEL RICHIE: We were just possessed. A lot of us had never met each other before. I didn’t know Springsteen. Billy Joel, you’re meeting at the same time you’re actually creating. I don’t know that we could ever pull that off again.

DEADLINE: Was there an attempt to level the playing field with all the artists?

NGUYEN: You’re in that room with the greatest singers of different generations — of all generations — at that time. I think in the beginning, people were maybe not checking their ego at the door. Kenny Loggins says there was definitely a sense of ego coming into that room. But as the night grew on, Lionel’s just sort of running around, trying to put out a lot of fires. In the film, he’s right on the edge of his seat, leaning in all the time, and he’s got these eyes of wonder, and anxiety and excitement. And then you have this Master General in Quincy, who’s able to wrangle all these superstars and do some brilliant strategical things, like making sure they’re all singing together in the same room, so they’re all looking at each other. They also made sure there were no publicists, managers, agents or handlers in the room.

Dionne Warwick and Stevie Wonder at the recording of ‘We Are the World’

Netflix

RICHIE: No glam in the room, either. Diana Ross, no glam. Dionne Warwick, no glam. Nothing in the room but us. It was like our first day of kindergarten. It was a wonderful time, and we all came together to create something for the world. And I see it, and I cry every time.

DEADLINE: The most uncomfortable person in the room seems to have been Bob Dylan. Surprisingly, he was having trouble singing his lines in the song.

NGUYEN: I think we can all relate to being at a party or a social event and feeling like Bob Dylan. I really love Bob Dylan. He comes in very nervous, but at the end, I think we’re all rooting for him. It’s a really beautiful and touching moment in the film, but if you think about it from his perspective, he rarely would sing a song that someone else wrote. In this case, he’s literally singing a Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie-written song. So I think he’s a bit perplexed as to how to sing it. And so, with the help of Quincy, Lionel and Stevie Wonder, he’s able to achieve it.

DEADLINE: Another surprising moment was when Sheila E. confided, in a new interview for the film, that she felt “used” — that she was only asked to participate because they wanted Prince, whom she was dating at the time.

Sheila E. interviewed in ‘The Greatest Night in Pop’

Netflix

NGUYEN: When we did that interview with her at A&M (now Henson) Studios, it was just heartbreaking. The whole crew, everyone, just went silent. And she told me after the interview that this was the first time she’d ever said that on-camera. So that moment was really vulnerable for her, but her participation in the film shows that at the end of the day, she still believes in the project. It wasn’t Kumbaya, although that’s what came out of it eventually. Throughout the night, there was a lot of drama, and a lot of tension. We see a lot of anxiety as the clock ticks down to the morning.

DEADLINE: What were some of the other unexpected moments?

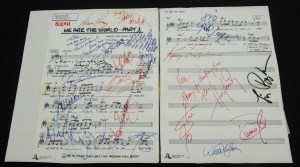

Soloist booth song sheet used for the 1985 recording of ‘We are the World,’ individually signed by the artists involved.

Clive Gee – PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images

NGUYEN: During a break, Diana Ross asked Daryl Hall for an autograph, and that really humanized things. And just knowing how big Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder and Michael Jackson were at the time, but everyone was just respectful and admiring of the other artists. One of the beautiful things about this film is that these great icons — people who are larger than life in many ways — are vulnerable and nervous. At the end of the day, they helped each other out to achieve something that was bigger than themselves.

DEADLINE: When the song came out, there were some who panned it.

NGUYEN: I love Bruce Springsteen’s comment about this. He literally says you can judge the song aesthetically, but it was a tool, and as a tool, it did what it needed to do.

RICHIE: As writers, you hope that you write something meaningful. In the case of Michael and myself, we were thinking about an anthem that we could leave to the world forever. And I think we accomplished that. I mean, I went to my grandkids’ recital and they sang, “We Are the World.” They said, “Sparrow, your grandfather wrote the song with Michael Jackson!” [Sparrow is the son of Nicole Richie and Joel Madden]. It’s transcended the generation we were in for generations to come.

DEADLINE: Have you heard from any of the artists in the film?

Huey Lewis, Sheila E. and Lionel Richie at the L.A. premiere of ‘The Greatest Night In Pop’ January 29, 2024.

Gilbert Flores/Variety via Getty Images

RICHIE: Bruce loves it. I heard from Cyndi Lauper. She said, (mimicking Lauper’s New York accent) “Oh my Gawd, I’m so sorry! I messed us up!” I said, “You don’t have to apologize!” And Huey Lewis is still going, “I don’t think we’re going to make it,” to which I say, “Huey, it’s been out for 40 years!” He had to fill in for Prince, and the PTSD is still affecting him! (Laughs)

NGUYEN: This wasn’t an intention, but the film is quite a celebration. It’s a joyous film, and that’s because everyone who spoke about that night remembers it so vividly. I think Sheila E. — even though she made the comment that she felt used, it’s still one of the things that’s the apex of her career. I think it only brought memories of joy, and optimism, and hope and thinking that by doing what you love to do — be it singing, be it a camera operator, be it a musician or a record producer — you could help change the world for the better, just by creating a song that has meant so much to so many people around the world.

RICHIE: Someone said to me, “Lionel, you need to write another ‘We Are the World.’ I just said, “Play it again. We don’t need to write another one. We just need to wake the world back up again.”