New York is a city full of windows, looking out and looking in. A shifting play of rectangles, the city is made up of boxes upon boxes. People live in them, breathe in them, glide up them, sleep in them. Artists, too, make their work in them, and painters confine what they see within the four corners of their frames. You can understand why artists worked with geometric abstractions here: it’s in the multilayered landscapes that morph in and out of infinite squares and strokes.

Last week I relocated to New York for a few months. I’ve always loved this city, but I’ve never stayed longer than two weeks. I’m based just above the East Village, and already when I wake up I’m enmeshed in the noises outside. Although I’m on my own, there’s a comforting feeling that I have everyone around me, wrapped up in our boxes, about to embark on the day ahead.

There is something about the density of the city that dissipates time: 7am quickly becomes 10 past five. Never a still moment – the lights and sounds keep the city flickering and awake. The poet John Ashbery called New York “an aggregate of people and buildings that just go on and on until they stop. The hushed moment enshrined here is the product of infinite works and days and the compounds thereof that constitute a life.” Being here makes me think about all the artists who have inhabited this place, the lives they lived. But I’m also curious about how they made time – and had room – to work.

How can artists translate the intoxication of the city into an image that is still but alive? One way was by painting the view through their windows. From the mid-20th century to as recently as the last decade, Lois Dodd, Jane Freilicher and Alice Neel – whose homes doubled as their studios – caught the changes in their skyline from day to night. You can tell they’re in Manhattan by how closely pressed up against the windows they are.

Dodd, the only living artist of the three, has been painting the view from her loft apartment since the 1960s. She once said: “That’s what I discovered about windows when I first started – here’s this frame and all I have to do is fill these rectangles, and if you put it in the right place, it’s all very organised, if you can get your head in the right place.”

One of Dodd’s works, 2nd Street View, November, 2016, is a cityscape filled with light. Looking through the window panes, it captures the crispness of a New York morning and verges on abstraction: a study of colour filled with browns, pastel yellows and a bright blue so electric that white seeps through from underneath. Dodd has devoted as much of the painting as possible to a golden tree and the blue sky, as if to latch on to the nature that grows in the city. When you notice a blossoming tree or a single flower sprouting out of the pavement, you hang on to it because it’s so rare. Once, when a tomato plant sprouted on a piling in the East River, it made headlines in the New York Times.

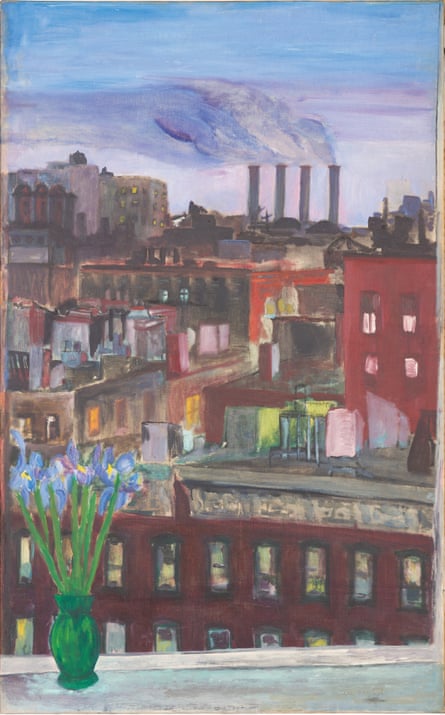

In 1954, Freilicher painted Early New York Evening. She was part of the downtown painting scene and kept a studio in lower Manhattan. Like many artists, she escaped to Long Island for summers and weekends but because she didn’t have a studio there, she always returned to the city to paint the weather and light from memory.

As if to hold on to that glimpse of nature, in Early New York Evening she marries the cityscape from her apartment on 11th street with a bunch of cut irises. Mediating between inside and outside by placing them on her window sill, she blurs the boundary between interior and exterior and the tightness of both spaces. The irises give a sense of life blooming, but also of fragility and temporality – perhaps the transient lives that flow in and out of the city.

Neel painted on the Upper West Side. In 107th and Broadway, 1976, the frame of the picture becomes the frame of the window. Silvery blue shadow covers the white prewar building across the street, indicating the closeness of the building next door. Each window has its own feel, as if it is a picture of the person who inhabits it. This work makes us imagine all the stories that once went on inside those windows, and still go on today.

All three artists know the skyline so well. But the city changes too quickly for a painting to capture the acute moment of looking outside. These scenes, although based on real-life views, are always bound up in imagination. When you’re so swallowed up by a towering greyness, you have to savour every element of brightness, of light, in order to hold on to that powerful, fleeting energy the city brings.