AJ Tracey is braced for a backlash. For years, the west London rapper has been someone who says he gets “stick for everything for no reason”. “Every action I’ve ever done in my whole life, since I was a little kid, has been looked upon negatively,” he adds.

As he announces the launch of a fund to help Black students thrive at Oxford University, he has no reason to believe it will be any different. The AJ Tracey Fund aims to address “historic underrepresentation” at Oxford, the top university in the UK. Working with St Peter’s College, Tracey, 28, hopes to attract students from underrepresented backgrounds and provide support to help them succeed, from financial assistance to mentorship opportunities.

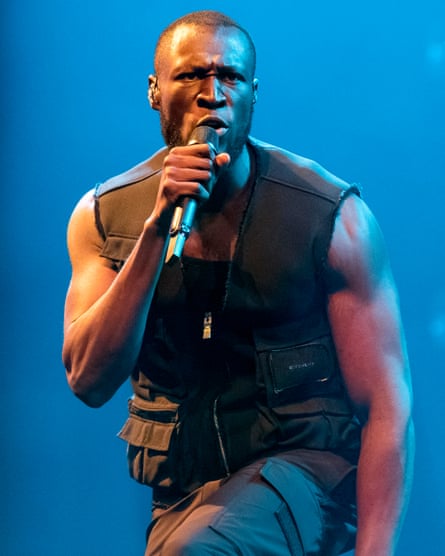

It sounds like a positive thing with the potential to transform lives. But when fellow rapper Stormzy announced a scholarship for Black students at Cambridge, trolls branded him racist and “anti-white”. “It’s crazy,” Tracey says, rolling his eyes. “At the end of the day, a large portion of the population is always going to have a very uneducated and misguided view on these kinds of happenings. Even if I were to say, ‘Yeah, I want to help every student, not just Black or ethnic students’, they’ll just say it’s a PR stunt.

“I think, in general, for anyone who doesn’t understand why Black people who have managed to become successful want to help Black kids, it should be self-explanatory. The whole country is catered towards white people and we’re just trying to level the playing field by helping Black kids.”

Growing up, Tracey didn’t see himself as the type of boy who could go to Oxford or Cambridge. Looking back, he would have loved to: he enjoyed school, got good grades and aspired to be a lawyer. But as a mixed-race Black teenager raised by a single mother in Ladbroke Grove, one of London’s most unequal areas, it felt like an out-of-reach fantasy – not even worth thinking about.

“I truly believe that I had the potential to go [to Oxford or Cambridge],” he says. “But it was just understood that if you’re from an impoverished upbringing or ethnic background it’s very hard to get in. Even if you’re intelligent, even if you know you can get those grades, it just feels out of reach. Unfortunately, the society that we live in, you know, it doesn’t favour people from a background like me. It’s not a sob story, it just is what it is.”

Some people around him managed to buck the trend: he remembers one girl at his school who got in and “did really well there”. “But I also know two other girls, Black girls, who applied for Oxford, who had some of the highest grades in my school who were denied. And there wasn’t a reason. We were all looking at her like she’s one of the smartest and she didn’t get in for reasons unknown. So why would we bother applying?”

He did go to university in the end – London Met – but dropped out of a criminology degree to pursue his music career. It wasn’t a bad experience – there were lecturers who “genuinely, passionately care about the kids”.

“But unfortunately the establishment isn’t one of the best academic-wise. I just felt like, at that place, I wasn’t really reaching my potential,” he says.

The AJ Tracey Fund, he says, will aim to help young people reach theirs. The criteria is “pretty vague, because I didn’t want to limit who it’s going to help,” he says. But the main goal is to help ethnic minority students on their journey through Oxford. He will be donating £40,000 a year for the first three years, after which it will be reviewed.

Having his name attached to it might “inspire people to think, ‘AJ Tracey’s cool, I listen to his music and he’s from the same kind of background as me. And if he cares about that stuff, maybe I have the right to want to go there’,” he says. He’s also planning to do outreach work in underprivileged communities. “I don’t like it when, in the end, kids are sitting there like really, really bright, getting their grades, and that kind of upper echelon is blocked for them.”

The other key aim of the fund will be supporting students once they are at Oxford. “Obviously, being a minority in England is one thing, but then being a minority at your place of education is quite difficult. Obviously, if they live in Oxford as well then they’re also a minority there. So just basically in every category, they’re a minority and that’s always going to be hard,” he says. Support will be awarded from the fund on a case-by-case basis, including for practical things – like train tickets or other expenses to “support the student experience of those from low-income backgrounds”.

Working with St Peter’s, which is unusual among Oxford colleges for having had Black undergraduates since its foundation in 1929, was a natural choice. “They specifically try to get people more of a mixed background, and they’re already working on that task. So for me, it felt like a no-brainer, if the train is already up and running, to help it go,” Tracey says. “I didn’t just walk in there and think, ‘Let me just randomly sling money at a random cause, you know.” Judith Buchanan, head of the college, said she was “delighted to have AJ Tracey in our world”. “With his generous support we look forward to seeing current and future talented Black students flourish in their time here,” she said.

Tracey is optimistic about the impact the fund could have. “Success can be even as small as the current students saying that their time [at Oxford] was a lot easier,” Tracey says. “But who knows? I don’t mean to be one of these eternal optimists but, genuinely, one of these kids that we’re talking to right now could just be the next prime minister. If they become prime minister and make the country 100 times better and then say, ‘You know what helped me a little bit? When I was at uni, AJ Tracey’…” he trails off.

As well as helping individuals, Tracey sees his role as positively affecting the culture at Oxford. Discussions about the curriculum and the calls for the removal of a statue of the British imperialist Cecil Rhodes, which sparked national debate, are the types of conversation to which he might contribute. “For me it’s about gauging how the Black students feel about that. When I’ve got my foot in the door, these are all things that I can go and talk to them about,” he says. “I don’t want to be on the outside, trying to tell people what to do with the establishment. I need to be inside trying to make a difference.”