At the record label Chrysalis in New York, we had a Wednesday marketing meeting every week. I was a young executive and the president came in and said, “I just came back from England and we signed a super talent.” I think she was 19 – it was Sinéad. This was before she shaved her head. When we heard [debut album] The Lion and the Cobra it was one of the greatest meetings I’ve ever attended – it was staggering, this record. It came out and we promoted it in a very unorthodox way. The key was getting it to go up the American college media charts, which it did and we took it to No 1. There were remixes of Mandinka and various other records – we had an MC Lyte version of I Want Your (Hands on Me).

Sinéad was terrific, so smart. And you could see at that young age she was very torn about stardom and recognition. The first day she landed, we decided to have dinner. We were going downtown, and I don’t know who made the decision to have a limousine but she wouldn’t get in. She wanted to go in a van. And then we got to Tower Records – the buzz was already out about Sinéad and a DJ was playing the record. She got very upset and said to me, “If there was a hole in the ground, I would crawl into it right now. Please tell him to take it off.” And I said to her very nicely, “It’s a homage. It’s respect.” She said, “Please, I don’t want to hear it. Please, please, please.” And we left. That was the contradiction of fame and recognition.

Live, she would always have hip-hop artists opening for her. That was her thing. No one was doing that. Not the commercial producers, but the really rock, hip-hop, political people in the business that had a voice – she gave them a voice and she had them opening for her. She befriended [Public Enemy’s] Hank Shocklee. She and my wife were also very close. We had babies at the same time: my second child, Maxie. Sinéad had come here and she was so lonely, not having her baby with her. She said to my wife, “Deborah, can Maxie sit on my lap?” She just wanted to hold her. She was so sweet.

I got to work with Sinéad again. In 1992, she’s getting ready to release the album Am I Not Your Girl. She got booked on SNL. Sinéad was not getting a lot of love at the time – she was controversial, she hadn’t had a hit in a while. Anyway, first song, Steve Kingston and Brian Phillips – two of the most influential people in the world of alternative rock radio – look back at me and said, “We’re adding the record Monday.” Thumbs up. Everybody’s great. We’re breathing.

And of course, the next performance was when she did War, and she ripped the picture of the pope. I will never forget it. Everybody froze at SNL. The music producer Liz Welch went from jubilation to tears. No one stopped it, no one knew what to do. We walked back to the artist’s dressing room. I don’t think she knew what she just had just done. The magnitude of it. She was in a room by herself which was kind of sad and lonely, because it was a heavy moment in history.

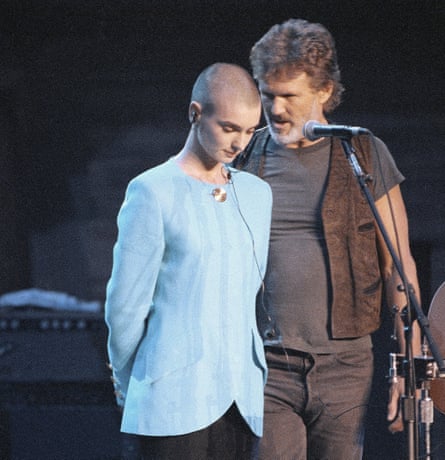

I remember knocking on the door. I went in and she was talking to herself. Her hands were behind her back, she had her socks on and she was doing something between poetry and chanting. I didn’t know what to do. People were upset and we got blamed, as if we were complicit. And then a few days later, she’s invited to the Dylan concert at the Garden [where she was loudly booed by the crowd]. I was there and I will never forget what Kris Kristofferson did for her. He hugged her, he put his arm around her, and he really got her through it. That was beautiful.

She was totally cancelled and then people would say, months and years later, “She was right, you know, we shouldn’t have done that.” The mob was horrible. The boycotting and blacklisting. People weren’t judging the music. The fear of not playing a record, or not adding a record to your playlist? Give me a break. It really did hurt her because she was speaking from the heart – she was an artist, and she had a very strong point of view. Her delivery was rough. She could alienate people.

She never recovered after that. No one judged the music, that’s what I was very pissed off about. Being outspoken should not be a penalty.

Two years ago, her manager Fachtna Ó Ceallaigh reached out and asked if I’d be interested [in working with her again]. I felt at that moment – not judging the music – that we had two beautiful runs together and I can’t do it again. I have a higher tolerance for artistic freedom and integrity and license and most people don’t. And I was right, because the world now is so woke, and so less open to chance, to open voices, than they were then. And I don’t regret my decision not to do that dance again.

But I only have great memories. Very often I’m asked, who are the most brilliant artists you’ve ever worked with? Nine out of 10 times, she comes in first. Not that she’s bigger, better, but that’s my gut response. She was more than a singer, more than an interpreter of songs. She was somebody who spoke the truth and wasn’t afraid of the truth. Prophets and poets, you always say after they pass away, or when it’s too late, that they were right. And what did she say that was wrong? About the abuses of the church? About mental health? About the children of the world? She was right. I knew her as a mother. She was a very compassionate, soulful person.

By the way, she drove me nuts professionally – she was the most frustrating artist of my career. But a brilliant one. I wouldn’t trade it for anything. I have a very heavy heart today.