“Full of carnage and tension,” is how Nik Colk Void describes playing with Factory Floor, the ferociously intense, wildly hyped group who created a clattering concoction of post-industrial electronic rock, noise and live techno.

That intensity contrasts starkly with Void herself. When she bought her first Fender Telecaster guitar, she sanded off the red paint because she felt it was too much of a statement. At a recent solo show, when playing her song Interruption Is Good – a crisp, bristling piece of electro-techno – the yelps and eruptive dancing from the crowd forced her to hide behind the desk to mask her reaction. Even in Factory Floor, her face was often hidden behind a curtain of hair.

“I want people to take the music for what it is, not the personality behind it,” she says. Searching for and escaping a sense of identity has been a tension throughout Void’s life. She longs to “revert back to before I recognised my reflection in the mirror for the first time at seven. I miss the visceral connection to my world I had before that – the freedom to explore and learn with no concerns of how and where to fit in.”

Performing live in an improvisational way – be it solo, or with Factory Floor, Carter Tutti Void (with Throbbing Gristle’s Chris & Cosey) or her duo with the late Peter Rehberg, NPVR – has been crucial to shedding this feeling of being hyper-conscious. “Becoming self-aware fogs everything,” she continues. “Off-stage I am methodical to a degree I would call boring! Taking chances on stage and jumping into situations that aren’t familiar helps push my ideas forward – it’s the only time I can let go and stop the worry.” Void describes her career as “everything in reverse. All the shows and collaborations are a point of entry to working out what my own musical language is.”

She speaks it clearer than ever on her excellent debut solo album Bucked Up Space, much of which was made in the Norfolk countryside – where she moved with her now ex-partner, Charlatans frontman Tim Burgess, and their child – trading a mice-infested London warehouse for a more serene creative environment.

“I miss the speed of the city but it was more important to give my son a place of ease,” she says. Navigating a new solo career while being a single parent has been a rewarding learning curve. “He inspires me and I understand myself more by watching him grow. I feel like I can offer him confidence to do things his own way – that gives my work purpose.”

Despite living remotely with no street lights or shops for miles, Void hasn’t changed tone. “My music hasn’t transformed to easy listening,” she says. She describes it as a bridge between techno, ambient and avant garde; her album is also a deconstructed guitar record. “I love reinventing the way I play guitar,” she says. “I have this love-hate relationship with it, but the familiarity of that sound is something that can’t leave me.”

That love-hate relationship goes back to another pivotal moment as a seven-year-old, attempting to grapple with the instrument for the first time. “I wanted to be good but it hurt my fingers,” she recalls. It was the last joint present she received from her parents before they separated, “so it had an emotional tie and I couldn’t make it work”, she rues. She changed and swapped guitars but none worked – some didn’t fit her body, while others drew tuts from sound men manning her gigs. “I felt this air of unworthiness and I had to prove I was good.”

The sanded-down Telecaster shifted things from hate to love and she began experimenting with idiosyncratic techniques inspired by Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo and the late Glenn Branca. “No riffing, but violin bows, sticks and noise.”

Void’s rendering of the guitar into something almost unrecognisable – feedback recordings that are spliced and then re-triggered with sequencers – is symptomatic of someone who cringes at the limelight; she allows the manipulated output to be the star of the show. “Absorbing myself in the process of making is my identity,” she says.

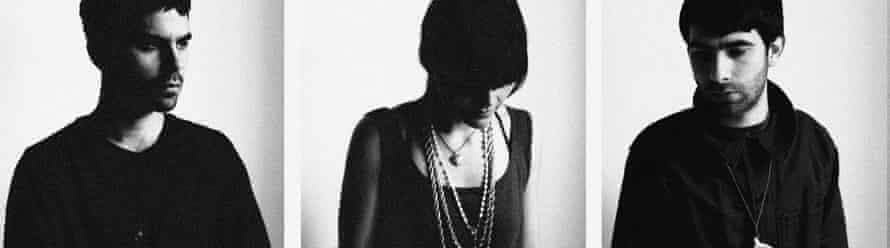

Her sense of herself had been inhibited by the huge buzz that encircled Factory Floor. “The pressure and expectation was overshadowing our development,” Void says. “When you realise you’re not learning anything from each other any more you need some space.” Their last studio album was in 2016, but time apart has been a blessing and now the original three-piece line-up are writing and preparing for a return. “We’re super keen to take what we’ve learned individually and bring it together,” she says.

In the meantime, though, as she gears up for shows to play solo album material for the first time, Void may need to prepare herself for more hiding under the desk. “I find direct praise difficult to handle,” she says. “I’m used to playing experimental shows in front of puzzled audiences.”