Recently, Chan Marshall was driving to a rehearsal studio in Los Angeles. It was days before she was heading to Europe for a run of dates that includes a night at the Royal Albert Hall, recreating Bob Dylan’s infamous 1966 show: the one where he played electric and a crowd member yelled: “Judas!” As she drove, she listened to the setlist: Visions of Johanna, It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue, Desolation Row.

Close to the studio, Marshall – AKA Cat Power – glanced in her rear-view mirror and saw her ex-boyfriend in the same line of traffic. “A lane over, two or three cars back, in a fancy car, on his phone,” she says now. It was years since their acrimonious breakup and she had long felt an absence of closure. That day, though, driving in the sunshine, listening to Dylan, she was struck by how little animosity she felt. “I had love and kindness in my heart for this person, which is a really good feeling to have after so long carrying around this ugly shit.”

He drew closer. She drove slowly, lifted her sunglasses, intending to smile at him. Just Like a Woman came on. Marshall sings the lyric: “‘And if we meet again, introduced by friends …’” It seemed fitting. “And he pulls off, and I smile, and he doesn’t see me.” Instead, the van in front brakes suddenly. Marshall brakes. Her belongings lurch into the footwell. The van proceeds and Marshall is driving again, picking up speed.

She sees children playing at the school where she hopes to send her son and suddenly the world feels as if it’s running in slow motion. “I pull over and the tears come,” she says. “But they’re not tears of pain, they’re tears of absolution.” The scent of bougainvillea floats through her open window. The moment suddenly seems magical. “I was thanking God, and I was thanking God Dylan,” she says. “Because that wouldn’t have happened to me if I wasn’t doing this concert.”

To spend time with the 50-year-old Marshall is to grow accustomed to this kind of anecdote – her conversation is unfiltered, conspiratorial, prone to detour and filled with fate, signs and predictions. Ask how she is and she will declare “I’m madly in love!”, show you photographs of her beau, tell you how a psychic said she would meet him, that it would be an easy love. “Sorry,” she says, “I’m babbling, but I’m nearly finished.”

It is early afternoon in Glasgow, and we are drinking coffee in Marshall’s hotel room. She has turned off the lamps and pulled back the heavy grey curtains. Her two notebooks, one red, one blue, have made way for a room service tray, laden with coffee pots and bread. When the waitress returns with some jam, Marshall thanks her in Polish, then lights the first of many cigarettes, the smoke blooming as she sits in a chambray jumpsuit, hair swept up, heavy eyeliner freshly drawn.

Written down, the car anecdote seems meandering and half-consequential, but Marshall tells it with an urgency and unexpected beauty. It’s a remarkable skill, one that has fired her 30-year career: an unrivalled ability to charge even the simplest of lines with emotion and colour. The lyrics for her 2018 album, Wanderer, were as spare and direct as they were on her 1995 debut, Dear Sir, but their recordings were rapturous. Famously, one of her earliest gigs saw her standing on stage at a New York dive bar, playing one chord on a two-string guitar and repeating the word “no” for 15 minutes. It’s partially her dusky, sacred voice. But it’s also her intimate understanding of sound and space. In person, and live, Marshall is filled with nervous energy, moving restlessly around the stage, mumbling thanks to the audience, worrying about the lights. Then she sings, and something stills her.

This gift has made Marshall a consummate interpreter. Earlier this year, she released Covers, her 11th album and third collection of covers, following 2008’s Jukebox, and 2000’s The Covers Record. As she made her way through songs by Iggy Pop, Nick Cave and Lana Del Rey, the record proved a masterclass in phrasing, a lesson in what she leaves out and includes.

“When I want to do a song, usually the only reason that I’m playing it or recording it is just because I love the song and I want to hear it,” she says. It is the only real light Marshall can shed on her approach. When she reinterpreted Rihanna’s Stay for Wanderer, paring back the verses, distilling the song to its essence, it was simply because she had heard it in a cab as she drove through Miami. “And I just started crying. Something in my life at that time [meant] I needed to hear that song. I’d just had my son and one of my best friends from New York visited, and I got a babysitter and we went to a karaoke place and I played it 16 or 18 times, over and over.”

Jukebox also includes her version of Dylan’s 1979 track I Believe in You (she took the liberty of changing a couple of lines). She can’t remember the first time she heard his music, but throughout her early life in the US south, in which her itinerant family was frequently apart, he seemed always to be there, cutting through the “sonic majesty” of the Beatles records, her mother’s Ziggy Stardust phase, her father’s blues records and her grandmother’s George Jones, hymns and Johnny Cash.

His music, she says, was “like a slow train coming. He was like Santa Claus or Father Time, an ingredient in my life. And there was something that really reminded me of church with Bob, the elegance of the prose, the poetry. I thought it was simple to understand, I felt like it was like reading a newspaper. I always loved him.”

As she entered her teens, Dylan suddenly drew into focus. “There was nobody else,” she says. “Patti [Smith] said it once, when I was hanging out with her a long time ago: ‘Bob, he’s like my boyfriend.’ He was her boyfriend, in her mind. And that’s kind of what happened to me.”

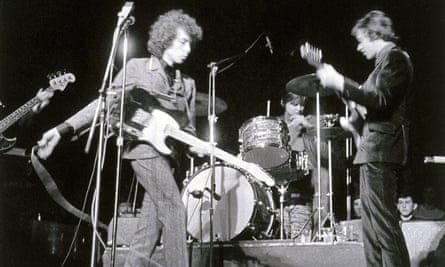

The Royal Albert Hall show will recreate the erroneously titled bootleg recording that was actually made at Manchester Free Trade Hall in spring 1966, surfacing several years after the event and officially released in 1998. The first half is an acoustic set, and the second played electric. It marked the pivotal moment in Dylan’s career when he turned away from his folk roots, incurring the wrath of some of his audience.

To Marshall, there is something holy about this moment. “There’s all the folk loyalists, and then this kid comes, this Beat poet dude, and starts putting something that’s rock’n’roll into something that’s not to be touched. That changes the course of music history and informs everything.”

She is keen to sing this performance as straight as she can, not to reinterpret the songs, as she often would. “It’s important for me to not do my thing,” she says, then clarifies. “I’m not being Bob, not at all. I don’t know how to describe it – I’m just recreating it, that’s all. But not making it mine. I had the inkling that I should protect that period of time and him making that crossover. It’s like this precipice of time that changed music for ever.”

There is also something hallowed about the Royal Albert Hall to Marshall. She likens it to the Vatican, or to “some old mosque or a living place like a cathedral”. She first saw it in DA Pennebaker’s 1967 Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back, and whenever she has been in London she has visited but never stepped inside. “My heart is racing, I’m terrified,” she says of Saturday’s show, fiddling with the brass-coloured buttons on her jumpsuit. “It’s not like: ‘Oh what will Bob think?’ It’s like: ‘what am I doing? Am I doing something right?’” She exhales and presses her palm to her chest. “I’m going to cry.”

Marshall has met Dylan twice. The first time was backstage at his show in Paris. She had found out a week before that she would meet him, and immediately grabbed a notepad and wrote what would become Song to Bobby: “‘I wanna tell you / I’ve always wanted to tell you / But I never had the chance to say …’” she sings now. When they met he was full of questions. “‘Are you here recording? Are you on tour? You got the band with you? You solo?’ He knew me already,” she says, still slightly awed. “I was like: ‘I wrote a song for you!’ And he’s like: ‘I want to hear it!’ So I sent it, but I never heard back.”

The second time was the night before we meet in Glasgow. Dylan is playing in the city too and the pair are staying in the same hotel. And so she was in the bar, a good martini down, when he and his entourage arrived. “It’s Chan!” she told him. “Chan Marshall!” (They spoke briefly and he put her on the guest list for the following night’s show.)

Between these two encounters came the time she was invited to meet him after his show in Pasadena, but somehow did not. It is another long anecdote, filled once again with diversions and double-backs and a dubious ex, who insists they leave the show just as Dylan strikes up I Believe in You. They reach the car as Dylan hits the second verse, and Marshall refuses to get in so that she can hear him singing. “And I’m just waiting, and I’m listening,” she says, and through the smoke she beams. “He changes the lyric – he changes the lyric to the one that I sang.”

Cat Power Sings Dylan takes place on 5 November at the Royal Albert Hall, London