Sometime after leaving Walt Disney Concert Hall on Sunday afternoon, milling around and talking to others struck by the power of Zubin Mehta’s performance of Mozart’s Mass in C Minor with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, I took my phone out of my pocket and powered it up. The first message on the screen was the announcement that the Grammy for best choral performance had gone to the L.A. Phil recording of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony conducted by Gustavo Dudamel.

Well, yes. The lead chorus in that magnificent recording of Mahler’s massive choral “Symphony of a Thousand,” happens to be the Los Angeles Master Chorale, the same chorus that, even with a reduced number of singers suitable for Mozart, had just held those of us in a nearly full Disney Hall glued to our seats. The Grammy is but the latest in a recent string of reminders how much the Master Chorale matters.

The Mozart Mass and Grammy come on the heels of a celebration of the 20th anniversary of music director Grant Gershon, who has made the chorale the finest-by-far major chorus in America and one able to serve exceptionally wide needs.

Those needs include beguiling the traditional audience that the chorus has nurtured since its formation as one of the Music Center’s founding resident companies in 1964. . At the same time, the Master Chorale has been equally successful in beguiling a diverse new audience with great works, whether noted or neglected, of the past. Audience members new and old, along with music new and old, sit side by gratifying side.

Two weeks before Mehta’s Sunday matinee, Gershon led just such a new/old concert in Disney. With impeccable performances, he balanced his trademark exuberance with his other deep-thinking trademark of meditative introspection.

He set the tone with a serenely fateful performance of the “Prayer for Ukraine” that is regularly sung at the end of Ukrainian Orthodox services, and then turned to two rarely heard and radically different sacred works. Handel’s fulgent “Dixit Dominus” features flamboyantly dramatic choral writing. The contemporary composer Arvo Pärt’s “Te Deum” is the other extreme, a mystical rendering of a Christian hymn accompanied by samples of a wind harp’s low drone.

Three days later, the Master Chorale held a gala in Disney honoring Gershon that included performances of a dozen short pieces, 10 of them by a sundry Gershon-esque collection of living composers, the outliers being Bach and the 16th century Orlando di Lasso. Typically of Gershon, and maybe only Gershon, he began with singer-songwriter Moira Smiley’s “Stand in That River,” which includes the memorable line, “When you stand in that river, angels sing in your head.”

The devil singing in Lasso’s head followed. In an excerpt from the composer’s inexorably moving, end-of-life “Lagrime di San Pietro” (Tears of St. Peter) which Peter Sellars has staged for the chorus, an inconsolable Peter bitterly complains that he’s “experienced such ingratitude from you.”

“Don’t take it personally,” Gershon joked to the audience. “It’s just a song.”

In testimonials live and recorded, a host of composers and conductors paid Gershon tribute, regularly reddening his face. He was called a “water sprite” by Ricky Ian Gordon and a “prophet for change” by Esa-Pekka Salonen.

The short, mostly a cappella pieces, conducted by Gershon and the chorus’ associate artistic director, Jenny Wong, were all over the map.

They included examples of Meredith Monk’s extended vocal techniques, a warmly sultry premiere (”The Open Hand”) by Michael Abels (best known for his score to the horror film “Get Out”), an ethereal version of Morten Lauridsen’s popular “O Magnum Mysterium” (which featured violinist Anne Akiko Meyers), Reena Esmail’s Indian-spiced “TaReKiTa” and the merry gibberish of Nilo Alcala’s “Tip Tipa Kemmakem.”

And yet, as its contribution to Mehta’s performance of Mozart’s Mass vividly demonstrated, this most modern Master Chorale remains rooted to its very beginnings. Mehta, who opened the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in 1964 with the L.A. Phil, is a kind of paterfamilias to the Master Chorale, having employed it regularly from the start to perform with the orchestra.

Known as the “Great” for the size of its near operatic ambition, Mozart’s Mass in C Minor contains some of the composer’s most inspired choral writing. It begins with seductive choral solemnity. Glory to God is hard, but gloriously won by the chorus.

Peace, though, is only implied. Mozart never got around to finishing the Mass, which ends with a Benedictus but no “Dona nobis pacem,” no plea for the end of conflict. After an exceptional hour, Mozart leaves us with a benediction but without the peace offering.

The Benedictus begins with four rapture-seeking vocal soloists (sopranos Brenda Rae and Miah Persson, tenor Attilio Glaser and bass Michael Sumuel) and an accommodating orchestra in excited anticipation. Then, as if out of nowhere, a big double chorus, accompanied by an orchestra with timpani thumping, announces a grand Hosanna that lasts no more than 45 seconds for a dazzling but startlingly perfunctory blessing.

We don’t know why Mozart didn’t finish his Mass. It could be that he was busy and simply didn’t get around to it. It could be that the composer’s intension was to stir us to action rather than still us into easy apathy. Peace needs earning.

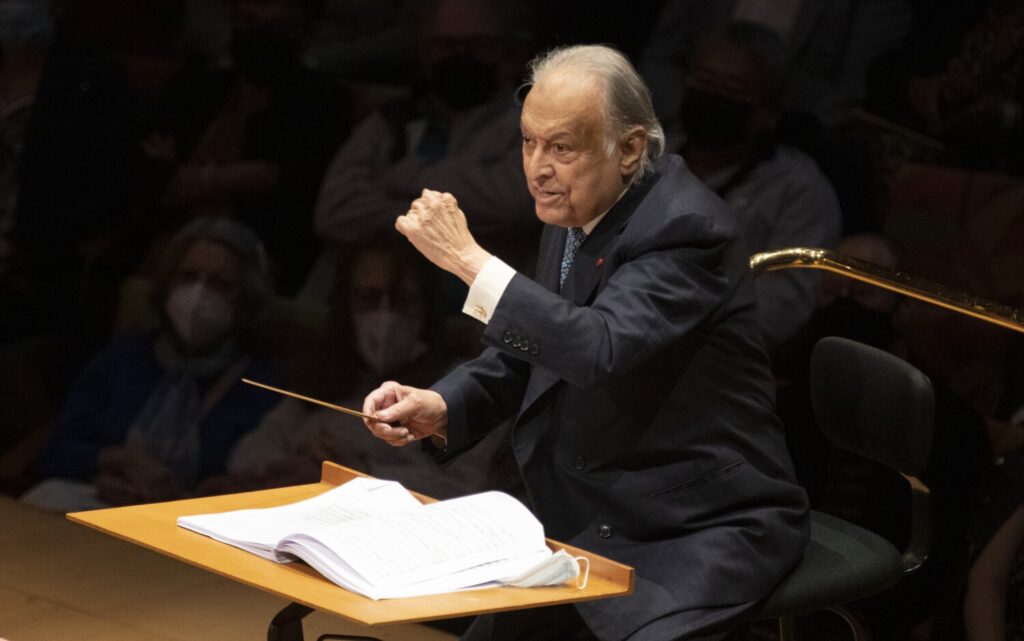

Mehta, who is almost 86 and conducts sitting, stood for the Hosanna, dramatically cueing the chorus and just as dramatically cutting it off less than a minute later. But, thanks to an overwhelming Master Chorale, we were left with an intense, distilled vision of what a benediction could be, if we could only hang on to it.

Next up: The Master Chorale, which performed “Fidelio” with Mehta and the L.A. Phil in 1975, joins Dudamel and the orchestra in a new production of Beethoven’s opera with Deaf West Theatre at Disney Hall on April 14-16.