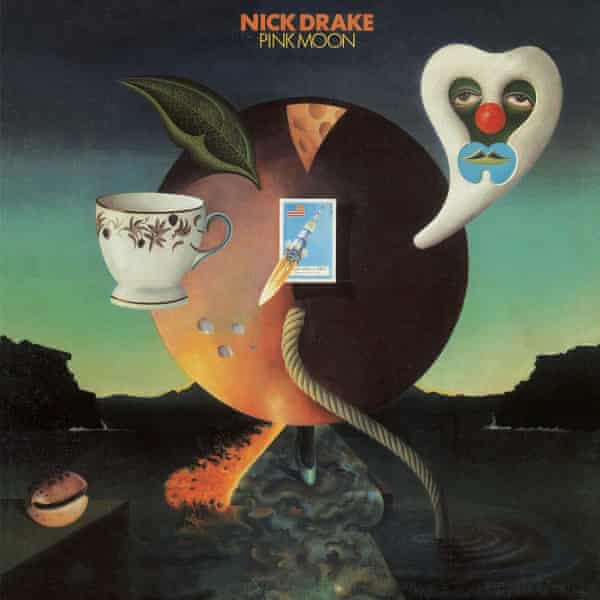

It is 50 years since Nick Drake made Pink Moon, his third and final studio album, yet his gossamer melodies still beguile us. They are as mysterious as their creator, who almost never performed live and rarely agreed to be interviewed. Songs from the album such as Know and Harvest Breed are fragile haikus, as luminous and elusive as the day they were first played.

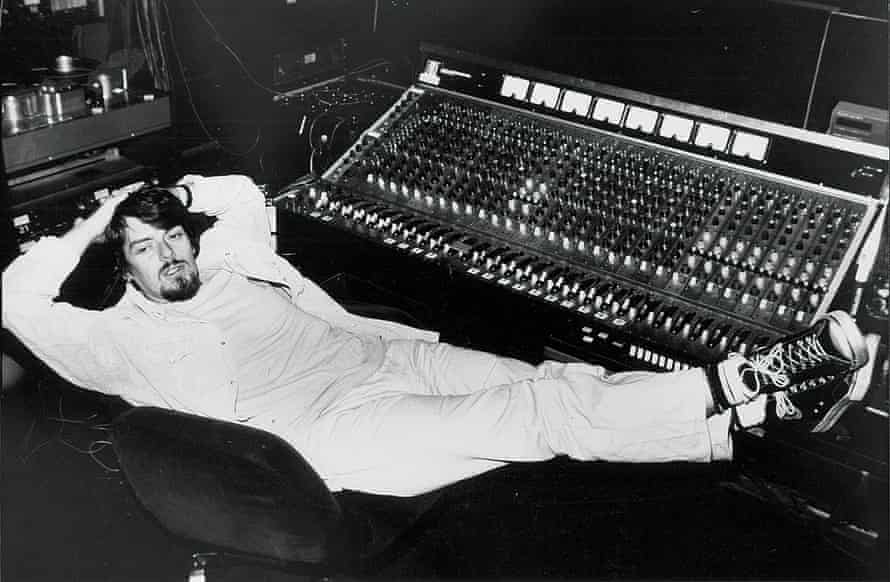

Keen to know more about the album, I contact John Wood, its sound engineer and producer. “I probably have a reputation for not giving many interviews about Nick, and in particular Pink Moon,” he says via email. “The overriding reason is that there’s not much to say about two evenings in the studio making an album that only lasts 20 minutes or so.”

Still, he graciously signs off with his mobile number and soon we’re chatting about Pink Moon. “You’ve described it as a folk record, but I don’t see it as folk,” he corrects me, right off the bat. “Somebody I knew described Nick’s music as an English version of a French chansonnier and I’d sooner think of it that way.”

It was at Sound Techniques, an 18th-century former dairy in London’s Chelsea, that Wood and his co-conspirator, Geoff Frost, set up their “English Arcadia”, building their own recording equipment. From 1965 onwards, the studio was a hub for US producer Joe Boyd’s roster of pastoral artists, reeling in the likes of Fairport Convention, Vashti Bunyan, John and Beverley Martyn – and Drake, who recorded all three of his albums there.

The first two – Five Leaves Left and Bryter Layter – sold only modestly, around 5,000 copies each, making Drake, who had depression, retreat into himself even further. He felt Wood was one of the few people he could trust. “One day,” recalls Wood, “he just rang up and said he wanted to go into the studio.”

What followed was unexpected. “It was a much more intimate recording,” says Wood. Gone were the mournful strings and the jaunty brass and in their place was simplicity: just Drake and his guitar. “I think he wanted to make a very direct and personal record. I thought, after the first couple of songs, that we would probably augment it a bit. Not a lot, but I was expecting him to get Danny Thompson in maybe.” (Thompson is the double bass player who co-founded Pentangle.) “After the second number, I said something and he just replied, ‘No, that’s it. That’s all we’re doing.’ And that was it.”

Wood could only have Drake at Sound Techniques late at night, over two back-to-back 11pm sessions in 1971. Does he have any lingering memories? “There is one – when we got to record Parasite. There’s this line: ‘Sailing downstairs to the Northern Line / Watching the shine of the shoes.’ Once I heard that, I knew this record was different.”

Pink Moon is often described as “desolate” and “bleak”, with Drake’s lyrics interpreted in light of his mental health. Place to Be contains the lines: “And I was green, greener than the hill / Where flowers grew and the sun shone still / Now I’m darker than the deepest sea/ Just hand me down, give me a place to be.”

Yet that is to ignore the album’s paradoxical elements, such as the sky-high hopefulness of the title track’s melody, and the rhythmic propulsion of horizon-seeking Road. “Nick played his guitar like a metronome,” Wood says as we discuss the pulsating quality Drake had. “I cannot think of anybody else I’ve ever recorded, with that little studio experience and at that age, who had that ability. It was extraordinary.” The singer was 23.

Drake was largely misunderstood and overlooked in his lifetime. Did his lack of commercial success affect him noticeably in the years before he died, at the age of 26, of an overdose of an antidepressant? “I have to say that I was disappointed,” Wood says. “I could not see why Five Leaves Left didn’t do better. People just didn’t get it. It wasn’t immediately accessible.” Drake didn’t seamlessly blend into the folk scene in the UK. Maybe if he’d been over in America, Wood muses, alongside the likes of Richard Fariña and Leonard Cohen, it would have been different. “The second time I was ever with Nick, I asked him what his influences were and he said, ‘Randy Newman and the Beach Boys.’”

And what about Pink Moon? “It’s just bizarre, the way it was discovered,” says Wood. In 1999, Volkswagen debuted a new advertising campaign with the title track – giving sales of the album a huge boost. “After I made it, I didn’t think it had commercial potential,” says Wood. “I never thought it would be a success.” Is he surprised that it is now, and that it has taken on such mythical status for fans? “Yes, I suppose I am.”

Wood didn’t play it for nearly 20 years after Drake’s death. “I felt it was intensely personal,” he says, pausing to reflect on its posthumous success. “In some ways, I don’t understand the wider appeal of it. I suppose a part of it is because of the way it was made, and because of Nick, and the stories surrounding him.”