A white-haired lady wanders Richard Neutra’s landmark midcentury house in Silver Lake at night, when she suddenly encounters a mountain lion calmly purring — and a grand piano in the room begins to play, on its own, Philip Glass’ “Mad Rush.”

It’s a scene from “Lightscape,” the latest hard-to-explain creation by Los Angeles artist Doug Aitken. The 65-minute film will premiere Saturday at Walt Disney Concert Hall with live accompaniment by the Los Angeles Master Chorale and members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic as part of the Noon to Midnight daylong festival of new music.

“Lightscape” will then transmogrify into an exhibition opening Dec. 17 at the Marciano Art Foundation in L.A.’s Windsor Square neighborhood, where Aitken’s film will be “exploded” onto seven screens and extended with physical artwork related to the film. Singers and musicians will regularly drop in on Saturdays and interact with the film in real time. A third iteration, in partnership with IMAX, is also in the works.

Aitken is reflected in one of his artworks in his studio. His project “Lightscape” is an immersive film installation and performance in Disney Hall and later will be an installation at the Marciano Art Foundation.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

The word “multidisciplinary” is such a dry, academic term for art that, theoretically, should feel more like a three-dimensional, surround-sound fireworks show. “Kaleidoscope” is a far preferable and more colorful description of Aitken’s ambition here, which takes stunning, impressionistic and often dreamlike images of ordinary people moving through extraordinary California landscapes, and stirs them into seemingly improvised songs as well as familiar minimalist masterpieces by composers like Glass, Steve Reich and Terry Riley.

In one passage, a man drives along L.A.’s concrete arteries, and several women on the street sing “freeway” in mystical harmonies. In another, strangers sing together from their cars in a drive-in theater parking lot, flashing their headlights at the glowing screen — their distance and location a reminder of the pandemic era.

In the Disney Hall performance, the same Master Chorale members seen in the film will be standing onstage and syncing their vocals to the mouths onscreen. This being L.A., a few celebrities turn up in the movie, including Natasha Lyonne (who may or may not appear at the premiere) and Beck (who will be part of the Marciano run).

Aitken, 56, is an equally hard-to-explain person. With ocean-gray eyes and a coiffed shock of white-blond hair, he almost could pass as a cousin of David Lynch. He has a similar aw-shucks, genial manner — easy to laugh and quick to offer a cup of tea — that belies the strange hive of imagery buzzing inside his head.

Born and raised in Redondo Beach, Aitken sprang from ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena to an early career in New York, playing with sculpture, light displays, performance, film and other media. His work has been projected on buildings, moving train cars and floating barges.

His mirror-clad house in Palm Springs, “Mirage,” got a wink in the Showtime series “The Curse.” Characters in the Nathan Fielder and Emma Stone show dropped Aitken’s name in conversation — which he learned only when his phone blew up with texts from friends.

“It was so weird,” Aitken said, laughing. “I realized I’m part of someone else’s fiction.”

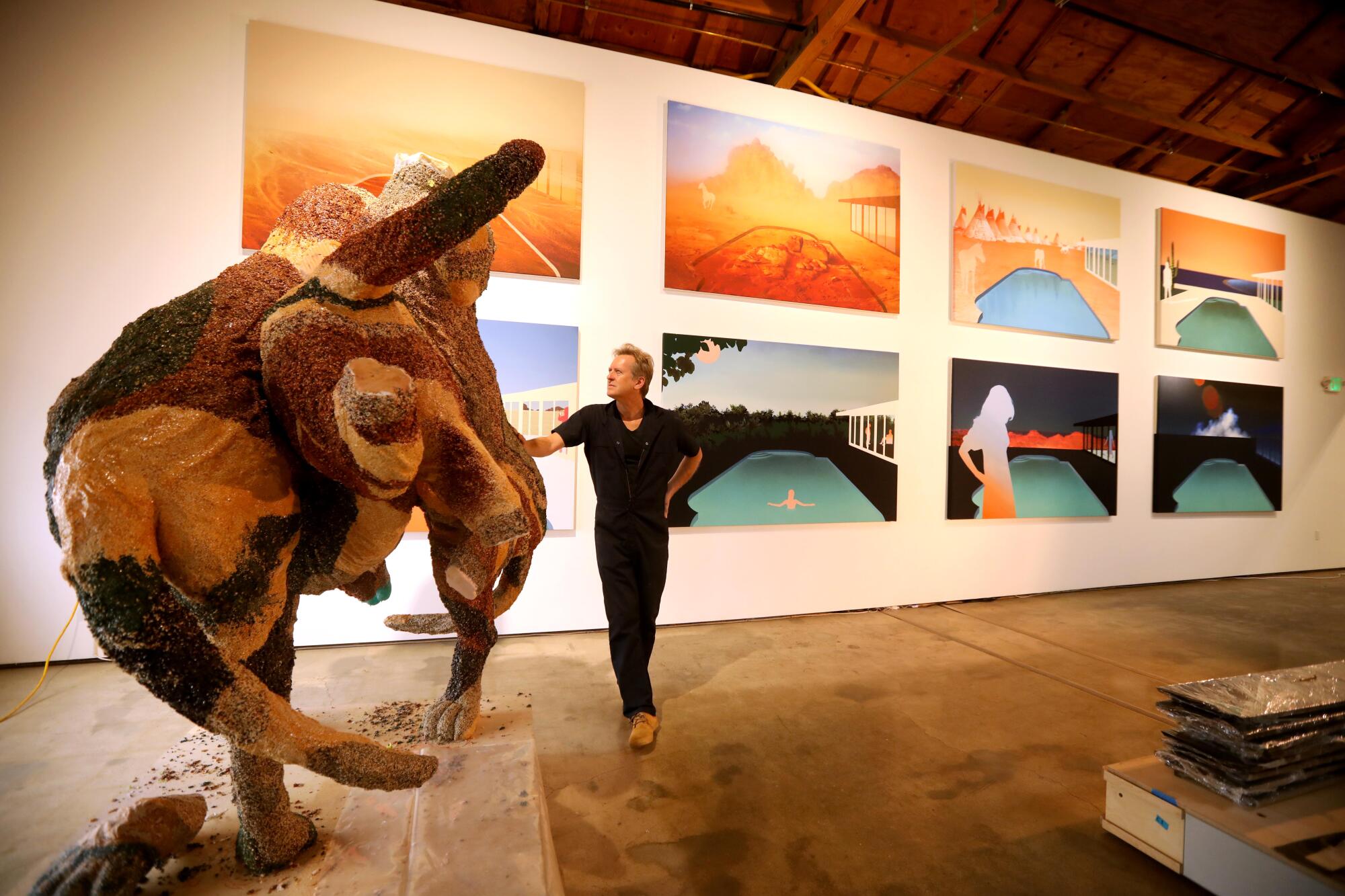

Aitken with untitled artworks that were hand-sewn works and painted on fabric, to be exhibited at Regen Projects in conjunction with “Lightscape.”

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

But meta layers of surrealism are on brand for Aitken, who said he’s “really interested in that idea of, like, where the line between fiction and nonfiction gets blurred.”

He recently acquired an old house near his studio in Mar Vista just so he could strip its parts for new art pieces. A few years ago he purchased an old transmission repair shop nearby and converted it into a workshop where he manufactures his sculptures and paintings with a small team.

Aitken spent so many years listening to music created for his artworks (including pieces by his good friend Riley) that, “like some kind of evolutionary lizard in the Galapagos,” he says, “I’ve kind of grown a palette over time of, like, what I’m after.” He isn’t a trained musician, but he does hear music in his head. A few years back he started singing words and phrases in his car at night, then had them sampled, looped and chopped up to form compositions.

A mutual friend connected him to Grant Gershon, artistic director of the Master Chorale, and Aitken proposed creating a song cycle.

“There were maybe 10 or 12 sheets of paper,” Gershon said, “and each paper had a word or phrase on it. I think one of them was ‘freeway.’ Another was, ‘There was a man who lived here / he doesn’t live anymore.’”

Aitken surprised Gershon by asking if he could record Gershon improvising. “He just had me sing some melodies, or create sounds with my voice that might match or complement or counterpoint the words and phrases,” Gershon said. Other singers from the Master Chorale later joined in and “laid the bricks of a cathedral one at a time,” Gershon said, “layering and combining and building and stacking and removing.”

“It was going to be almost a vocal earthwork,” said Aitken, who tends to think and speak in floating, unearthly concepts. “I wanted to have 30 to 80 vocalists in these different areas of the landscape, and a word or phrase is passed from person to person to person, creating a concentric ring or geometric patterns.”

This went on for almost a year — and then the pandemic hit.

In that weird, quiet time, the L.A. Phil approached Aitken about a commission. He proposed basing it on this quotidian word song cycle in conjunction with the existing instrumental pieces, and weaving the result into an interactive film piece. “Lightscape” was born.

Aitken in his Culver City studio framed by “The River,” a kinetic light and sound sculpture that will go on view at the Marciano Art Foundation.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“This project has more moving parts than I’ve ever had,” he said.

With a skeleton crew and Aitken as camera operator, he filmed improvised moments with non-actors, located strange and beautiful pockets of his home state to shoot, and arranged for a coyote, a horse and that mountain lion to take part.

“It was kind of this, like, six-month fever dream,” he said, citing inspirations such as Robert Altman and John Cassavetes.

He had Steinway program a player piano to perform “Mad Rush” with Glass pounding playing style, and he had his roaming camera observe the big cat’s response to the music.

“It seemed like it digged the piece,” Aitken said, as wide-eyed and sincere as he is when talking about all of his work. “Very mellow, actually.”