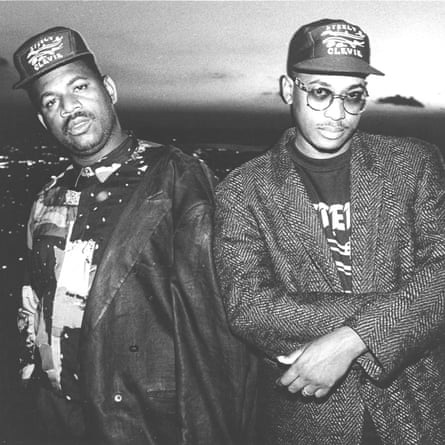

With the release of their song Fish Market in 1989, the Jamaican duo Cleveland “Clevie” Browne and Wycliffe “Steely” Johnson inadvertently changed the course of pop music. The track featured the first known example of what would come to be known as a “dembow” rhythm – the percussive, slightly syncopated four-to-the-floor beat that travelled from reggae to become the signature beat of reggaeton, today the world-conquering sound of Latin American pop.

Now, more than 30 years after Fish Market was released, Steely & Clevie Productions is suing three of reggaeton’s most celebrated hitmakers – El Chombo, Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee – for what they characterise as unlawful interpolation of Fish Market’s rhythm (or “riddim”), and are seeking the credit – and royalties – they say they deserved from the start.

Steely & Clevie Productions’ lawsuit cites 56 songs, including some of reggaeton’s biggest hits, such as Fonsi and Yankee’s Justin Bieber collaboration Despacito and Yankee’s Gasolina, many of which have amassed hundreds of millions, or even billions, of streams. A swathe of featured artists and co-writers are also named as defendants in the lawsuit, including Bieber, Stefflon Don and rising Puerto Rican singer Rauw Alejandro, as well as publishing companies and record labels. (Representatives for Bieber and Stefflon Don declined to comment; the Guardian has contacted representatives for Alejandro.)

A win for Steely & Clevie could have massive implications not just for reggaeton, but for pop music in general, which has increasingly looked to Latin American music for inspiration over the past decade. Thousands of other songs that use a dembow rhythm could be considered in breach of copyright, and this action could also set a precedent for future copyright claims based on foundational pop rhythms.

In Jamaica and Latin America, reuse and sampling of instrumental tracks without fear of being taken to court is common practice. “The underground scene in San Juan [in Puerto Rico] that gave rise to reggaeton was inspired by Jamaica’s sound system tradition of using popular instrumentals to propel new, live, local performances,” says Wayne Marshall, an ethnomusicologist specialising in social dance music at the Berklee College of Music in Boston.

When reggaeton was first developing, it had little economic value, and few of its progenitors had any idea that it would one day become one of global pop’s most significant forces. Now, reggaeton is a multibillion-dollar industry: Bad Bunny, currently the genre’s biggest star (who has also branched off into other styles), has been the most streamed artist globally on Spotify for three years running.

“Once reggaeton becomes one of the most popular genres in the world, producing some of the most lucrative music of the 21st century, it calls into question whether the same creative licence should apply to commodities worth millions of dollars,” says Marshall.

Indeed, Browne and Anika Johnson (the latter representing the estate of Wycliffe Johnson, who died in 2009), claim that Fonsi, Chombo and Yankee “never sought or obtained a licence, authorisation or consent” to use the rhythm that originated in Fish Market, and that they “continue to exploit, and generate revenue and profits from, the infringing works”. Browne and Johnson have requested a jury trial for their legal action.

The claim suggests that the success of Shabba Ranks’s 1990 hit Dem Bow – which included lawful use of the Fish Market rhythm, crediting Steely & Clevie as co-writers – inspired other artists to copy the rhythm. Browne and Johnson claim that the artists named in the lawsuit would have had access to Fish Market because of its wide availability, and that they also would have had access to Bobo General and Sleepy Wonder’s Pounder, another song from 1990 whose rhythm Browne and Johnson say is “substantially similar, if not virtually identical” to that of Fish Market.

While rhythms are not generally protected under copyright law in the US, a rhythm may be copyrighted if it can be proved that it is substantially unique or original. Lawyers for Fonsi, responding to Browne and Johnson’s action, denied “that all or any portion of … Fish Market is original or protectible”, and claimed that “no response is required”. Representatives of El Chombo directed us to a video on his YouTube channel in which he talks extensively about reggaeton’s history and songwriting. Representatives for Daddy Yankee did not respond to the Guardian’s request for comment.

To Katelina Eccleston, a reggaeton historian and creator of platform Reggaeton Con La Gata, the tradition of reuse in riddim culture shouldn’t exclude artists from getting songwriting credits. “This has been a long time coming,” she says. “It doesn’t take a scientist to see how [Fish Market] has been used and sampled and swapped around in reggaeton.”

Eccleston sees the case as rooted in a long-held racial hierarchy that extends across the Americas, wherein those with lighter skin complexion – the majority of reggaeton’s biggest stars – are often given greater privileges. In Eccleston’s view, this extends to Jamaica, where a large part of the population has a darker complexion than those in neighbouring Latin American countries. Jamaican genres such as dancehall and reggae, Eccleston says, are popular worldwide, but lack economic parity with reggaeton.

“The people who are making millions off this music are living at a different level than the people who wrote the music originally,” she says. “Everybody wants Jamaican music and culture, but they don’t want to make sure Jamaicans can eat.”

New York copyright lawyer Paul Fakler, who is not involved with the case, says that Browne and Johnson have been strategic with their request for a jury trial. “One of the key things in copyright law is that ideas are not protected, but unique expressions of ideas are,” he says. “So a lot of times when you have these copyright cases go to juries, you can get wacky results.”

Fakler notes that when a judge and jury are faced with the intricacies of musical theory, the verdict often becomes less about the music and more about the story behind it. He cites the 2015 Blurred Lines case, in which a jury found Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams guilty of infringing on the copyright of a 1977 Marvin Gaye song, as a watershed moment in pop copyright claims.

“The result wasn’t necessarily about anything that was relevant, but about the salacious elements of the story,” says Fakler. “That can have a way of pitting a jury against you when they have to then sit in the box and decide who’s right and who’s wrong and who’s credible and who’s not credible.”

Gregor Pryor, a lawyer specialising in entertainment and media, says that Browne and Johnson may be facing an uphill battle – in part because the defendants will probably “have a plethora of defences against copyright infringement at their disposal, which will make the plaintiffs’ argument more difficult to prove … The plaintiffs will have to prove that the defendant ever actually heard, or could reasonably be presumed to have heard, the plaintiffs’ song before creating the allegedly infringing song,” he says.

Pryor says it is hard to prove that someone has had prior knowledge of a song, meaning that the courts will have to consider a song’s popularity. “The use of language such as ‘foundational’ and ‘iconic’ being used [in the lawsuit] to describe the instrumentals are early attempts to signpost its popularity and show that access would have been likely,” he says. “Whether this point is successful or not will depend on the plaintiffs’ ability to demonstrate that the work was as popular as they have suggested, which may prove challenging.”

Major labels, attempting to pre-emptively avoid copyright lawsuits, have begun crediting artists who weren’t involved with the creation of a song when a newer track bears a resemblance to an older song. Recently, Olivia Rodrigo retroactively gave songwriting credits to members of Paramore and Taylor Swift for two songs on her debut album; in 2016, Beyoncé famously credited Animal Collective on one of her songs owing to a slight lyrical resemblance to their 2009 song My Girls.

Such a strategy is unlikely to have occurred to Fonsi, Chombo and Yankee when they first started minting hits. It may soon be up to a judge and jury as to whether they are liable to pay what many see as a long-overdue debt. “This has been the biggest elephant in the room since the creation of the music,” says Eccleston. “Once money got to the table, that’s when things changed.”