I’m not sure when I first listened to George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” which premiered 100 years ago this week, from start to finish.

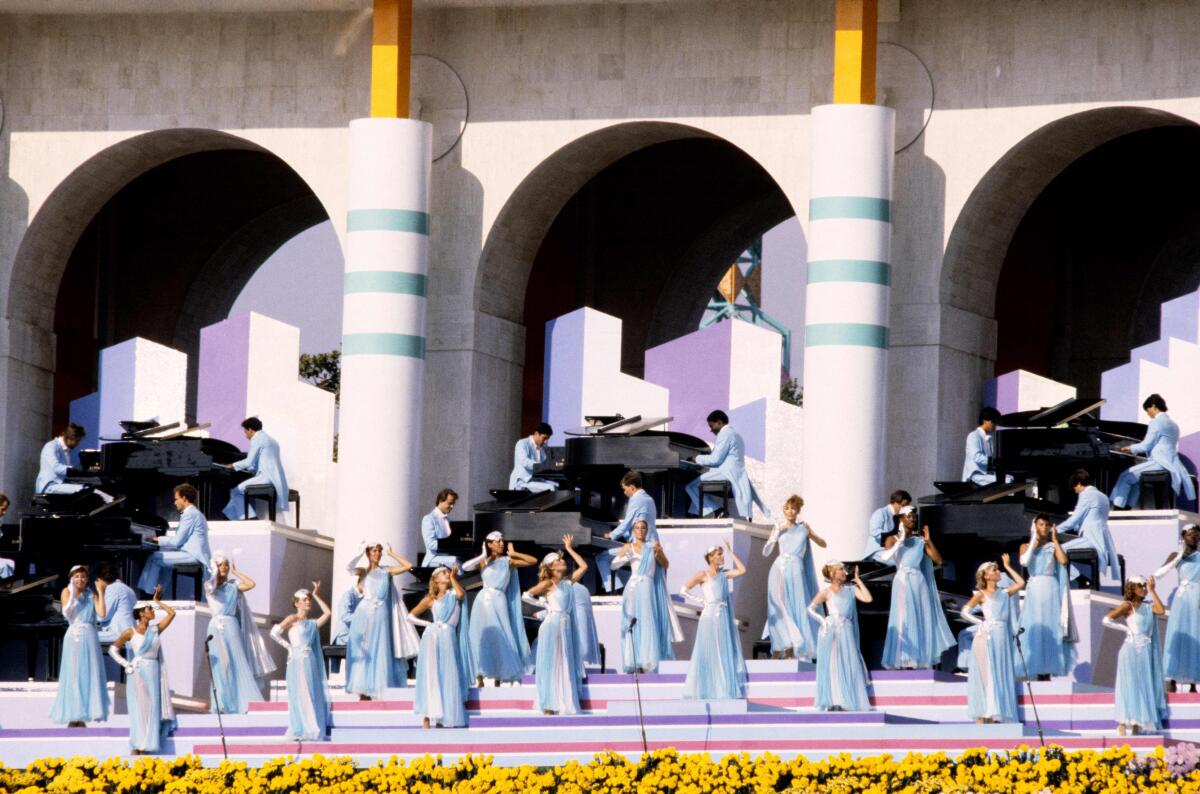

Snippets had played throughout the soundtrack of my life as a child and teen — the opening ceremony of the 1984 Olympics at the L.A. Memorial Coliseum, random cartoons, commercials for United Airlines, cameos in Disney productions. It’s one of those classical pieces, like Beethoven’s Fifth and Ninth symphonies and Bach’s spooky Toccata and Fugue in D minor, that long ago left orchestra halls to entrench themselves in the American psyche.

When I finally got through “Rhapsody in Blue” in its entirety, it was the aural equivalent of the Big Bang.

The wailing, breathless clarinet solo that kicks things off. The wry tubas and trombones that accentuate the opening section. The thunderous drums and cymbals that announce the beginning and end of movements. Elegant violins. Piano chords that jaunt along during solos and rise above the swirling, clashing chaos, demanding to be acknowledged.

George Gershwin, composer and pianist, at home in New York. The image is dated Sept. 1, 1934.

(CBS Photo Archive )

The composition was a revelation. It swaggered and stomped and skipped. It was unpretentious and rollicking — nothing that I had known classical music to be — and sparked an admiration for Gershwin’s creation that grows the more I learn about him and his times.

As orchestras around the country celebrate “Rhapsody in Blue” throughout 2024, it’s important to think of the piece as more than just music. In a year when Americans are fretting about our democracy in ways we haven’t for decades, it tells the saga of this nation — and offers a way forward.

As Gershwin often recounted, he wrote “Rhapsody in Blue” in a rush after reading a newspaper article reminding him of his promise to debut a new concerto mixing classical music with the jazz that was riveting the nation’s cool set at the time. Looking for a muse, the 26-year-old found one in the clangs, hisses and whistles of a train trip to Boston. That base allowed Gershwin to construct “a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness,” he told a music critic in 1931.

His final product nailed it, both musically and thematically. Hints of Cuban clave rhythms, Tin Pan Alley harmonies, Jewish melodies and piano licks swim through its overarching Romantic theme. The messy pace — alternately defiant, maudlin, weepy and bombastic — sounds like a country that was working things out within itself but nevertheless remained optimistic and confident about its future.

There was no better person to envision this sonic tribute to the United States than Gershwin. He never attributed any explicit political significance to “Rhapsody in Blue,” because he didn’t have to. He was the child of working-class Jewish immigrants who fled the tyranny of the Russian Empire for a chance at a better life in New York. His work wrestled with the questions that every second-generation American faces. Do you maintain the customs of the old country, reject them completely to fully assimilate into mainstream society, or do you grab the best of the two and mix it with what you pick up from other cultures?

Like many second-generation kids, he chose the latter scenario and lived it with gusto.

Gershwin made his decision in a city teeming with people from around the world, in a nation that saw the influx of foreigners as alien and threatening. Three months after the debut of “Rhapsody in Blue,” President Coolidge signed the Johnson-Reed Act. It severely curtailed immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe and created the Border Patrol to keep out Asians and Mexicans — the antithesis of everything that Gershwin’s ode to America celebrated.

“Rhapsody in Blue” is most identified with New York, as it should be — Gershwin was a Gothamite, he debuted it in Manhattan, and the best recording of it remains Leonard Bernstein conducting the Columbia Symphony in 1959 while playing the piano (too bad Bradley Cooper didn’t re-create the scene in his recent Bernstein biopic, “Maestro”). Yet we in Los Angeles should also claim a part of Gershwin and his genius. He decamped to Southern California with his brother Ira to plug away in Hollywood, seeing better times in Los Angeles instead of the East Coast. But George’s career was cut tragically short when he died in 1937, at just 38, after surgery to remove a brain tumor.

Dancers and piano players perform during the opening ceremony of the 1984 Summer Olympics at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on July 28, 1984. Eighty-four grand pianos played George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

(Georges Bendrihem / AFP via Getty Images)

One could only imagine what Southern California, gateway to Latin America and Asia, might have taught Gershwin had he lived.

His tour de force is aspirational, inspirational and offers lessons for all of us. Yet there’s always been pushback against the brilliance of “Rhapsody in Blue.” Bernstein once told the Atlantic that it was “a string of separate paragraphs stuck together with a thin paste of flour and water” and not “a real composition,” even as he described Gershwin as “my idol.” In recent decades, scholars have accused Gershwin of cultural appropriation for daring to be a Jewish man who fused his love of Black music with classical music — a fusion that reached its apogee with the opera “Porgy and Bess.”

Recently, composer Ethan Iverson wrote in the New York Times that “Rhapsody in Blue” was “the worst masterpiece” in the classical canon, describing it as “Caucasian,” whatever the hell that means. To think of it as corny and antiquated and “white” misses its revolutionary potential. Thank God the public has understood its truth all along.

There’s a reason why it’s a standard that symphonies trot out whenever they need a sellout (the Los Angeles Philharmonic will play it at the Hollywood Bowl this summer, site of many iconic performances featuring Gershwin’s oeuvre). Why eyes glisten as people rise from their seats when the orchestra reaches the rousing conclusion.

It’s unabashedly hopeful and proud of this country’s mess. It dares you to feel the same. It’s America at its best.