Photos courtesy of Federico Sargentone.

At Milan Design Week 2024, Loewe presented an exhibition of newly commissioned light-based works under the unassuming title, Loewe Lamps. The 24-person show was set in a James Stirling-designed industrial bunker, hidden beneath the elegant 18th century Palazzo Citterio. The juxtaposition of these two spatial qualities—the hyper-bourgeoise palazzo and its lush garden, and the essential, brutalist-looking bunker, worked well architecturally, and projected the exhibition into a sort of fine-art canon, which is often hard to find throughout the initiatives during Salone Del Mobile.

As I walked down the concrete, stark stairs to the show, I met Enrico David, an Italian artist based in London, who alongside Chiara Fumai and Liliana Moro, represented Italy at the 2019 Venice Biennale, and was presenting a curved table lamp in onyx for the Loewe exhibition. “I had already been making this lamp, so when Loewe asked me to participate, it felt right,” he told me. “As sculptors, we operate in this realm of objects that seemingly have no function, but then I realized that for the past 25 years, I have been also making lamps, so functionality is something that I incorporate in my work.”

For Japanese artist Genta Ishizuka, the theme of light motivated him to create a suspended lamp. “I’ve used aluminum tubes for air conditioning from DIY shops, and I made a knot with it,” he told me. Japanese lacquer covers the piece, in traditional black, while the lights that stem from this dark surface serve as an antithesis to it’s form. Similarly, Belgian artist Ann Van Hoey focused on materiality, using leather as a primary component in her piece, although she is a ceramist. In collaborating with Loewe, she transformed bowls she had previously produced in clay into a suspended leather bouquet.

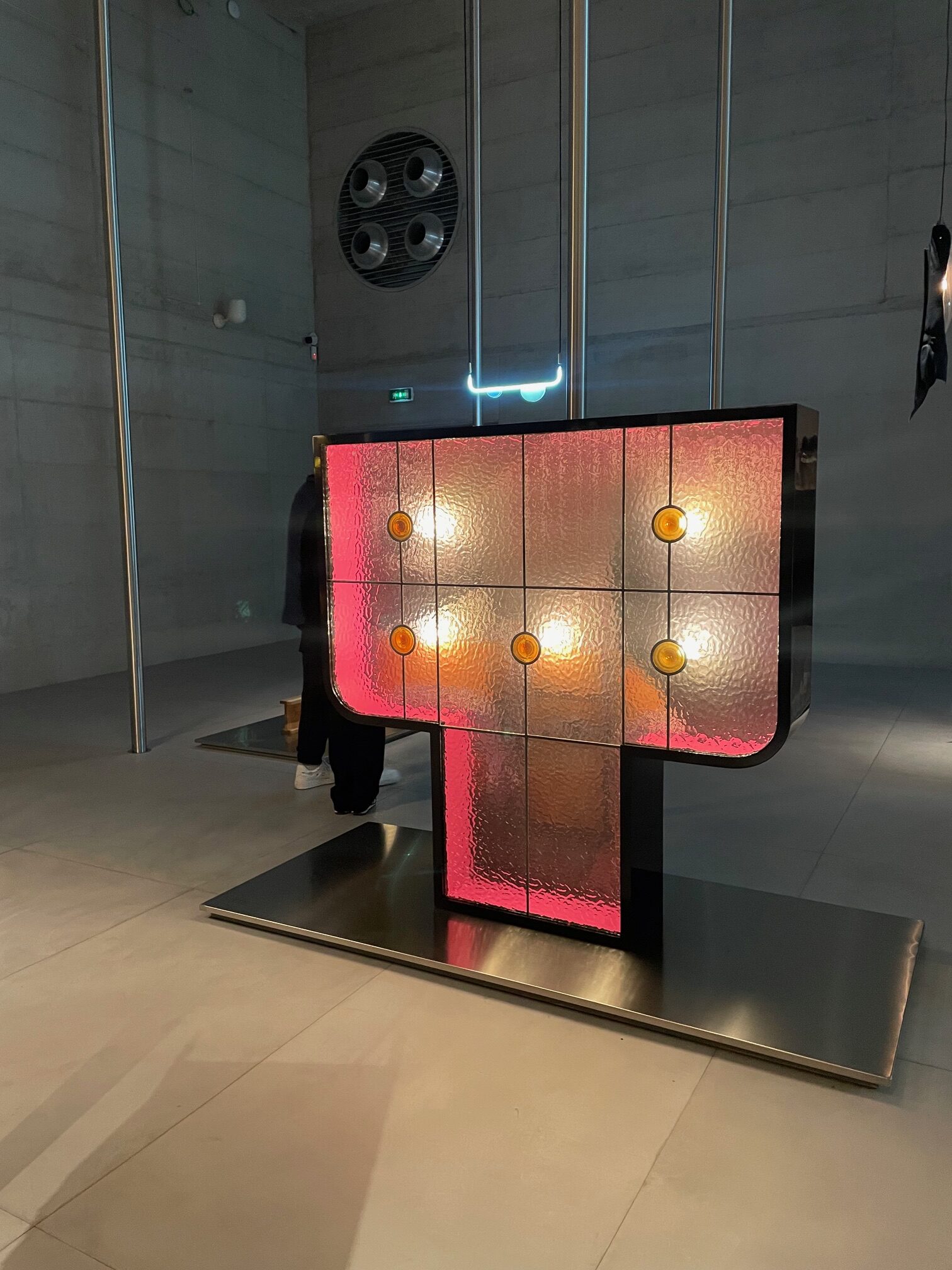

As I walked through the exhibition, I came across Alvaro Barrington’s work, which combined light, aluminum, and painting to represent a storefront shop. Is it a sculpture? Is it a lamp? Who cares? For the London-based artist, the shutter is a recurring element in his practice, mostly because in New York—where he’s from—storefront shops play a big part in the city’s social context. “I remember, as a kid, when an album came out, you had to go to the store and wait for the shutter to come up,” he told me. “I always thought of it as a moment of light, an opportunity.” John Dewey’s book Art as Experience came up as one of his favorite titles—and I agree. If Design Week demonstrates anything, it’s like Barrington says, “A beautifully designed product can be as poetic as a painting.”