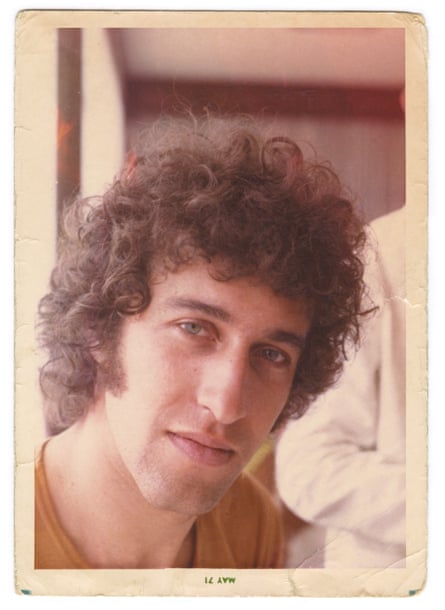

Almost the first thing Daniel Vangarde says when he walks into the Paris office of his record label is that he’s never done an interview in English before. Then again, he adds, he had never done an interview in his native French either until this morning. He never bothered talking to journalists at the height of his career, when he was a key figure in French pop: an artist, writer and producer behind an array of releases that range from the wildly obscure to the instantly familiar. And he certainly wasn’t expecting to start meeting the press aged 75: Vangarde had retired years ago, relocating to a remote fishing village in northern Brazil.

But then a record company unexpectedly approached him about a career-spanning compilation, named after Zagora, the label he founded in 1974, which piqued his interest. When they sent him the track listing, he told them that some of the songs on it weren’t his. They were – he’d just forgotten them entirely.

At least part of the renewed interest in Vangarde’s career is down to the success of his son, Thomas Bangalter, until recently one half of Daft Punk. It’s ironic given that hearing Daft Punk was one of the reasons Vangarde gave up making music in the first place: “I thought, this is the new generation coming and it will be difficult to compete.”

But Vangarde’s career is fascinating in its own right. It began with a bullish teenage plan to break into the music industry by simply writing to the Beatles and suggesting they let him join – “I was sure I could bring something to them,” he chuckles – and ended in the early 90s with Vangarde retiring in disgust after a series of bitter arguments with the French music industry.

In between, he pursued a career which was nothing if not diverse. At one extreme, he wrote protest songs deemed so subversive they were banned: his eponymous 1975 solo album came to commercial grief as a result of its lead single, Un Bombardier Avec Ses Bombes, an attack on France’s role in the international arms trade. “The big honour I had was that I did one television appearance and then it was censored in France. Even today, you cannot talk about that subject.”

At the other, he was the mastermind behind the Bouzouki Disco Band, whose oeuvre was noticeably lacking in attacks on the military-industrial complex: as their name suggests, they dealt exclusively in Hellenic-themed disco tracks with names like Ouzo et Retsina and Greek Girls. His CV also takes in huge international pop successes – Vangarde and his long-term collaborator Jean Kluger were behind late-70s hitmakers the Gibson Brothers and Ottawan, of D.I.S.C.O. and Hands Up (Give Me Your Heart) infamy – as well as fantastic cosmic disco released under the names Starbow and Who’s Who, and obscure Japanese-themed funk rock concept albums beloved of today’s crate-diggers.

The contents of 1971’s Le Monde Fabuleux des Yamasuki, have, as Vangarde puts it, “become a little bit fashionable” in recent years: the album has been sampled by Erykah Badu, included on an Arctic Monkeys-curated mix album and featured on the soundtrack of the TV series Fargo. It was remarkably ahead of its time: a mad, cartoonish blend of different musical cultures that also attempted to provoke what would now be called a “dance challenge” (the album’s cover comes complete with instructions on how to do the steps).

Vangarde was always interested in music outside the standard western pop canon. “I like to travel, I like exotic instruments, I listen a little to the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Stevie Wonder, but most of the music I love is African music, Arabic music, reggae,” he says. But Le Monde Fabuleux des Yamasuki’s inspiration didn’t involve much exotic travel. “You know the TV series Kung Fu, with David Carradine? That was the thing at the time. We thought we should do an album about kung fu, and that became a Japanese thing.”

He worked across a variety of genres – he reworked a track from the Yamasuki album in Swahili as Aie A Mwana, subsequently covered by, of all people, Bananarama – but it was disco that really turned his head, his mind blown after hearing Chic’s Le Freak in a Parisian club. Moreover, it was a genre that didn’t share the era’s traditionally dismissive Anglo-American attitude to French pop. Vangarde thrived, as did his countrymen Space and Voyage. “There were no prejudices in disco, I think because its audience had experienced prejudice – it was Black, it was gay. They were not in the position of being snobs.”

In fact, he loved disco so much that when the backlash happened, he felt impelled to act in the genre’s defence: to hear him tell it, Ottawan’s deathless wedding party anthem D.I.S.C.O. is effectively a protest song. “It was the time when they were burning the disco records in the US, and I felt crazy that people said this will stop: it’s a rhythm, you can’t stop people dancing to a rhythm. So I said we’ll do a song about disco to show that’s not over. And the rhythm didn’t stop,” he adds, triumphantly. “Because what is techno? A continuation of disco.”

For all his pop success and tolerance for a cheesy novelty song, Vangarde was always a curiously unbiddable figure, wont to turn down high-profile production jobs if he liked the artist too much, as in the case of reggae stars Third World or salsa supergroup the Fania All-Stars. “I didn’t want to be involved. I just wanted to be a listener – I didn’t want to lose that magic.”

Just how unbiddable became apparent in the late 80s, when he got embroiled in a battle with the French music industry, initially about royalties. Researching the subject led him to take up the cause of Jewish composers who had had their intellectual property rights – and the accompanying earnings – stripped from them during the Nazi occupation of France. This became a controversy that eventually involved then-president Jacques Chirac, but Vangarde says a subsequent official report into the matter was “all lies – a massive cover-up”: no money or rights were returned. It was another factor in his decision to retire. “I had a big fight with Sacem, the authors’ rights company. To write a song and give it to this company – why would I do this?” He shrugs. “I don’t do that any more.”

It’s fairly easy to see where Daft Punk might have got their famously uncompromising attitude towards the music industry. When their career began to take off, it was Vangarde who suggested they make a list of everything that they didn’t want to do and present it to any labels looking to sign them, which is how he ended up with a credit “for his precious advice” on their debut album, Homework.

“They did not want the label to be involved with the vision of the music, or the videos, or their image. This is one of the keys of their success, because when you go in the system, it has to please the A&R [people], it has to please the radio, and the music changes. Daft Punk were original, they had talent, and what they imagined went to the ear of the people with no interference.”

Vangarde says he has no desire to go back “in the system” himself. He says he never listens to the music he made in the 70s and 80s – “I wrote 350 songs, and I couldn’t sing you one of them” – and looks aghast at the suggestion that this new retrospective compilation might entice him back into the studio. “No, I’m very happy now. They wanted to release an album, I decided to do interviews for the first time in my life. And now,” he smiles, drawing our conversation to a close, “I will quit again.”