Marilyn Stafford’s career was hardly unsuccessful. The pioneering photographer quietly documented much of the 20th century – slums, celebrities, war zones, world leaders, everything. But she has never been celebrated like she is today. After the exhibitions dedicated to her fashion and street photography, reportage and portraiture, Brighton Museum is paying tribute to her with a full retrospective. The 96-year-old tells me she can’t believe what has happened – not least because she stored her photographs in shoe boxes under her bed for decades and pretty much forgot about them.

Stafford is on the short side (5ft 1in at her peak), glamorous, serious-minded – and a huge amount of fun. And boy does she have stories. Even her stories have stories. So we start in the Great Depression, when she was a little girl walking to the big department store downtown in Cleveland, Ohio, with her mother. She noticed that a girl ahead of her was not wearing shoes, and asked why. “My mother said: ‘Probably because the family can’t afford them.’ And I think that was one of my early eye-openers on reality.”

By the way, she says, her mother lived to 103, at which point she died of vanity. “She would have gone on more, but she was afraid to have her cataracts done and was going deaf. My mother was so vain that she wouldn’t wear a hearing aid, and she said: ‘When I can’t see and can’t hear any more I will kill myself.’ When she couldn’t see and couldn’t hear, she just stopped eating.” Stafford has a habit of telling macabre stories with relish. She is Zooming from her home in West Sussex. Her red lipstick is perfectly coordinated with her red glasses, her hair a magnificent white bob and she looks gorgeous. These days she is partially sighted, so her daughter, Lina Clarke, is here to help with the technology. I ask Stafford if she lives alone. She sounds horrified. “No! I have a cat called Minouche. But I call her Minou for short.”

Stafford grew up in a middle-class family – her father a pharmacist who had emigrated from the Baltics as a young boy, her mother a great beauty who dreamed of being a “lady”. When she was young, her parents hoped she would be the next Shirley Temple and sent her to bed with curling wrappers in her hair. Did she want to be the next Shirley Temple? “Not me! I hated it. It was so painful to sleep on those things.” But she did like acting, and between the ages of 10 to 18 trained at the Cleveland Play House, alongside Paul Newman and Joel Grey. “I learned the Stanislavski method. I think I’m probably the only Stanislavski photographer around.” She giggles. “Or was!”

She studied drama at university – paying her way by working at a local defence plant. Stafford was so convincing in one role, playing a nasty girl in a Lillian Hellman play, that her boyfriend said she must be innately obnoxious and dumped her. “Maybe he was just making an excuse,” she says.

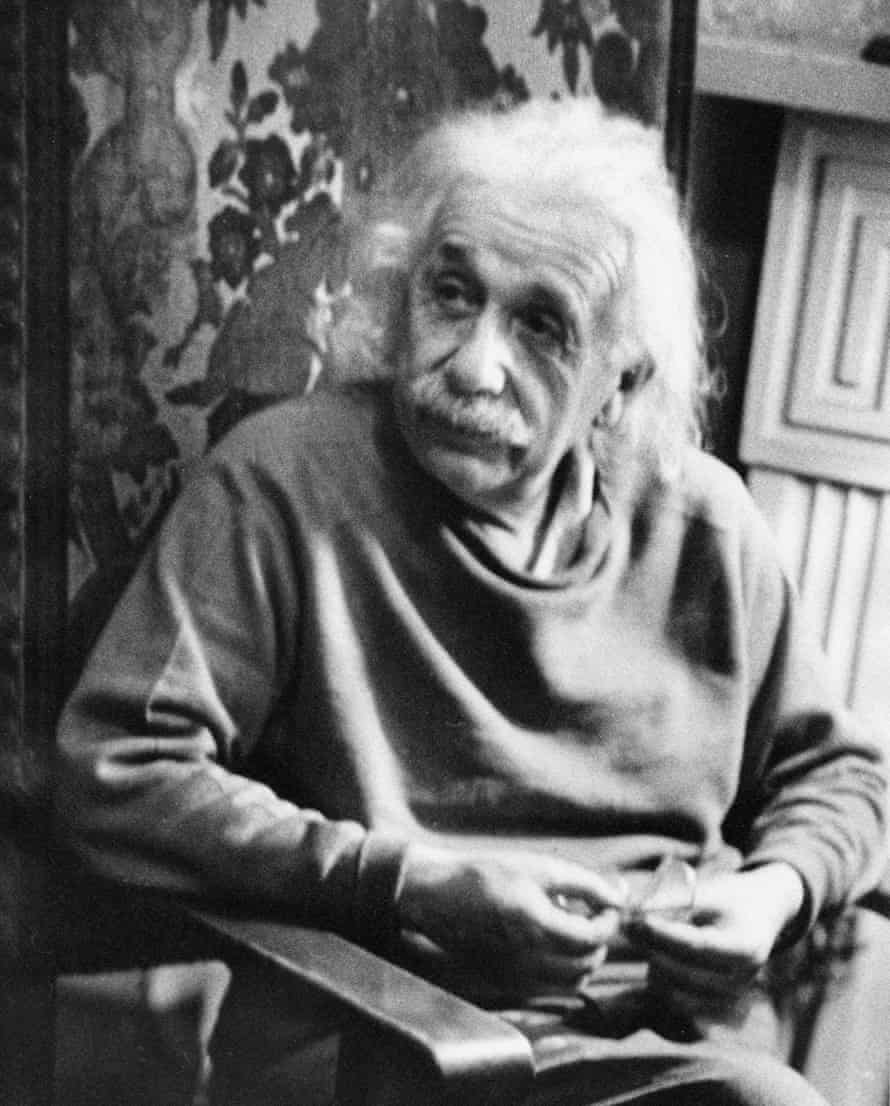

In New York, she played a few cameos in off-Broadway productions but struggled as an actor. Then serendipity took a hand. In 1948, two friends were making a documentary about Albert Einstein at his home in Princeton, New Jersey. They invited Stafford to go along with them and asked if she would take his photo. She had used her parents’ Box Brownie, but nothing more. “That’s when I was given my first 35mm camera. I was just thinking: ‘Oh my God, they’ve given me a camera I’ve never used before!’ I was terrified. Terrified. I go numb at moments like that. All I was aware of was that I had to focus and click the shutter.”

Her photos of the great physicist are wonderful – he’s smiling, crumpled, inquisitive and human. In one photo he looks as if he is listening intently. “Yes, he had asked how many feet per second go through the camera and the director explained to him. He was very serious about it, and he said: ‘Ah yes, now I understand, thank you very much.’” What’s behind the lovely smile in the other picture? “I’d like to think he was smiling at me!” Stafford says.

At 23, she set off for Europe on the back of another strange story. “My friend found out her husband was having an affair. He told her to go home to her mother while he sorted himself out. She said: ‘No way! I’m going to take a trip to Paris and I’m taking Marilyn with me and you’re going to pay for it’ – which he did.”

In Paris, she got a job singing as part of the ensemble at the prestigious dinner club Chez Carrère (apparently the only club the newly married Princess Elizabeth was allowed to visit). She must have had a huge confidence to be taking photos of Einstein one minute, singing in a top club the next? “I don’t know if it’s confidence. It’s what’s called in Yiddish chutzpah. You just do it.”

-

Street sleepers, Boulogne-Billancourt, Paris, circa 1950.

At the club she befriended the singer Eddie Constantine, who was dating Edith Piaf. Stafford found herself part of Piaf’s extended entourage, regularly invited to her home for breakfast along with Constantine and the many waifs, strays and celebs who shared her home. Charles Aznavour occupied an attic room, while the wife and children of Piaf’s former lover Marcel Cerdan (a boxing world champion, who had been killed in an air crash) also lived there. There is a fabulous photograph of Piaf in the book that accompanies the exhibition – dressed in white and laughing, the opposite of how you’d expect to see her. “That’s why I like the photograph,” Stafford says. “Because she’s laughing, and she did laugh.”

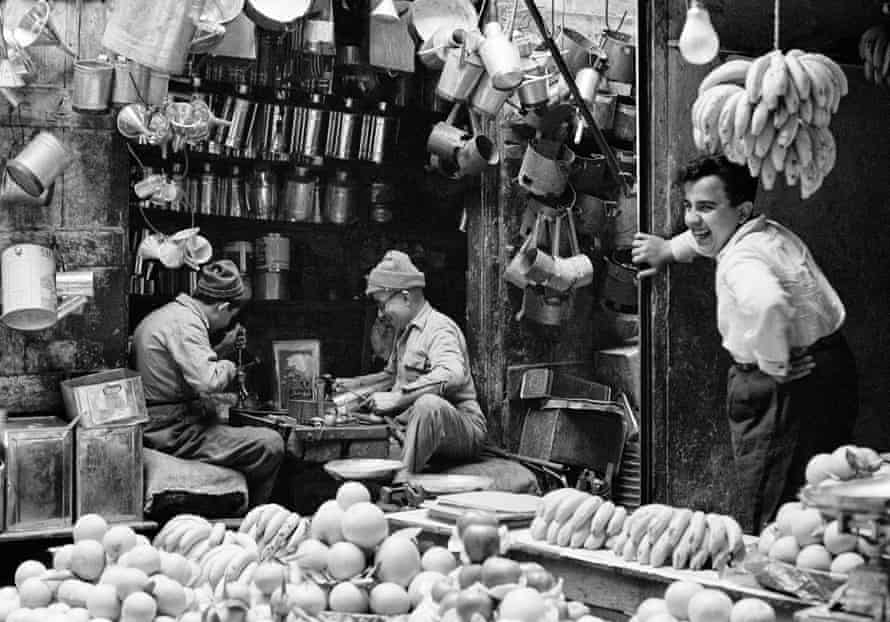

During the day, she would take the bus from the Left Bank to the end of the line where she photographed people in the slums of Boulogne-Billancourt. Some pictures are heartbreaking (a homeless woman asleep in a child’s buggy), others joyous (cheeky kids revelling in the camera’s attention). These photos tell stories in a single frame. Meanwhile, her fashion photography is stylish and funny. Because she was technically inept, she avoided studios and took her models on to the streets. In one picture, a beautiful model stands outside the Louvre in a long white coat, brolly in one hand, high heels in the other, and feet splayed – think Marilyn Monroe meets Charlie Chaplin.

In Paris, she befriended the photographers and Magnum co-founders Robert Capa, David “Chim” Seymour and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Capa asked her why men always cried rather than nibbled on her shoulder. “To this very day the same thing happens. Lots of men cry on my shoulder.” Would she have liked Capa to nibble on her shoulder? “I must say Capa was very attractive and I would have dearly loved to have more than a friendship with him, but he was older than me and I think he wanted more sophisticated women than me.”

Instead, Capa encouraged her to take photographs and suggested she become Seymour’s assistant. “I don’t like carrying heavy things and I was a coward, terrified to go into a war zone, so I turned down that generous offer.” That’s lucky, I say. “Yes. Both Chim and Capa got killed.”

She adored Cartier-Bresson. I ask what she learned from him. “I think I learned quietness – not to be obvious as a photographer. He would shoot without you knowing. I remember sitting at a cafe with him and he had a camera in his lap and he saw a photograph he wanted so he lifted the camera up, not to his face, just off his lap and took a photograph.” Did she use that technique? “No. I was not as clever as him. I just put the camera up and took pictures.”

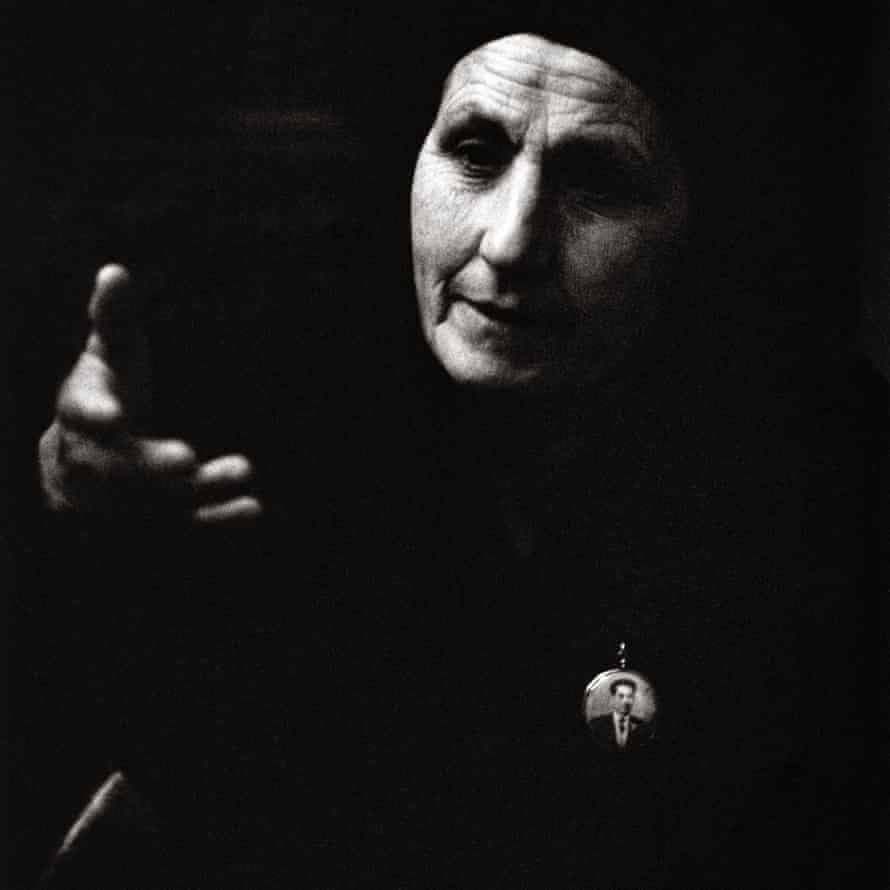

Stafford is being unduly modest. She had a wonderful eye. In 1956, she married a foreign correspondent and moved around the world with his job. In Italy, she took a memorable photograph of Francesca Serio, a labourer and activist who became the first person to sue the Sicilian mafia, after they killed her son. Serio has an astonishing presence – in one photo her face shines beatifically out of the blackest background; in another her gaze is harsh, and a single accusatory finger is raised.

When Stafford was six months pregnant with Lina, she travelled to Tunisia to document people in refugee camps who had fled France’s “scorched-earth” policy in Algeria. Now, she says, she looks at these photographs of refugees and thinks of Ukraine. “I just feel sick and sad all the time. It breaks my heart.” One portrait of a mother and child bears a striking resemblance to Dorothea Lange’s Dust Bowl images. She holds her baby tenderly but her eyes are a thousand miles away. Cartier-Bresson sent this set of photos to the Observer and two were published on the front page. It resulted in the Observer sending a reporter to cover the story of the refugees. Stafford began to feel that her photos could serve a purpose.

She has always had a gift of taking photographs of people, particularly women, that pose questions. Her subjects often seem far away, in reverie or despair – whether it’s the woman with the baby in Tunisia or Joanna Lumley, Sharon Tate and Twiggy back in swinging 60s London.

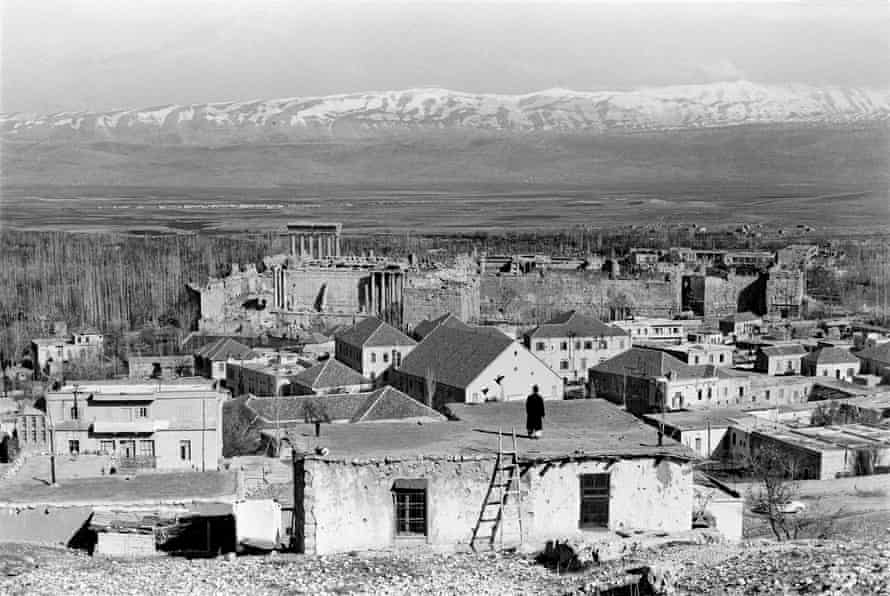

Throughout 1960, she photographed everyday life in Lebanon. The pictures were intended for a book, but the publisher thought there was too much grit and not enough glamour. It took 30 years to get the pictures published. “You don’t earn a living that way, do you?”

Stafford and her husband separated when Lina was young. He went to work in Moscow, she came to London. As a female photographer, she had always been in a tiny minority. Now as a single mother, balancing work with bringing up Lina was even tougher. Five years ago, she established the annual Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage award for female photographers. “It was with the aim of letting women have a little extra money that would help them in the event that they had to care for children and pay for that care or any number of reasons they might have.”

Her commercial work (she ran a fashion agency with the French photographer Michel Arnaud) subsidised more personal foreign trips to India, where she spent a month following the prime minister, Indira Gandhi. In 1972, she travelled to the new country of Bangladesh with the intention of taking portraits of some of the estimated more than 200,000 Bengali women and girls raped by Pakistani soldiers in the liberation war. Stafford returned home defeated.

“The eyes of the people I met had a look of such terror in them. Everybody. And I wanted so much to get the feeling and I never did. I photographed an awful lot of faces and eyes, but I just wasn’t able to capture it.” She had photographed people fleeing war in Algeria, but this was different. “Bangladesh was the first time I had seen the ravages of war first-hand and it marked me terribly because I was a real innocent. It’s one thing to read about war and see somebody else’s photographs, but to actually be there and see it … And I didn’t even go through the war – I just saw the after-effects.”

Did it change her as a photographer? “It did in a way, because when I returned I was offered a full-time job on a fashion publication and I turned it down. I didn’t want to spend my life taking fashion photographs when there was much more going on in the world.”

Stafford retired in her mid-50s. In her 70s, she married a Portuguese man who loved to tango and shared her values (he had been an active antifascist under the Salazar dictatorship). They moved to Sussex, where she organised poetry trails and got involved in a literary festival. Although he died a few years ago, she has kept herself busy, sorting out the shoeboxes under her bed and getting her archive in order.

She has done this with the support of the documentary photographer Nina Emett, who has co-curated the exhibition with Lina and edited the accompanying book. Again serendipity had a part to play. Stafford sought out Emett after seeing a photographic project curated by her on the streets of Brighton, and Emett fell in love with Stafford’s photography. “Nina has organised a group of people in Brighton called the Marilyn Stafford Working Group, whose aim is to promote my photography! It’s unbelievable.” She really does find it hard to believe that anybody could dedicate themselves to championing her work.

Now that her photography is displayed in galleries and museums, does she regard it as art? She hoots at the idea. “No! I was a working photographer. It was a marvellous, delightful way to earn a living,” she says. “I was just lucky.”

The Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage award of £2,000 is for female documentary photographers whose work focuses on solutions to important social and environmental issues. The 2022 award launches on 8 March in celebration of International Women’s Day. The exhibition Marilyn Stafford: A Life in Photography is at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery until 8 May. The book of the same title is published by Bluecoat Press.