Production designer Sarah Greenwood and set decorator Katie Spencer were working from a snow-covered, erupting volcano in Sicily during the production of Joe Wright’s “Cyrano” when the possibility of “Barbie” popped up. Their longtime collaborator, costume designer Jacqueline Durran, had recently wrapped “Little Women” with Greta Gerwig and had recommended that the writer-director consider Greenwood and Spencer to create the whimsical, colorful world of “Barbie.”

“Tom, Margot [Robbie]’s husband, sent me the script and it was completely bonkers,” Greenwood recalls. “There were no scene breaks. It broke the fourth wall constantly. It was 140 pages long. It was laugh out loud. I was like, ‘Wow!’”

“It was an amazing stream of consciousness,” Spencer adds. “And it was a real page turner. It was just so unexpected.”

A pink-hued film about Barbie isn’t necessarily something the pair, six-time Oscar nominees for such films as “Atonement” and “Darkest Hour,” had ever considered. But the unconventional approach to the storytelling and the possibility of collaborating with Robbie and Gerwig was too compelling to pass up. They decided to approach it similarly to Wright’s 2012 adaptation of “Anna Karenina,” where they built a singular world for the specific purpose of the story.

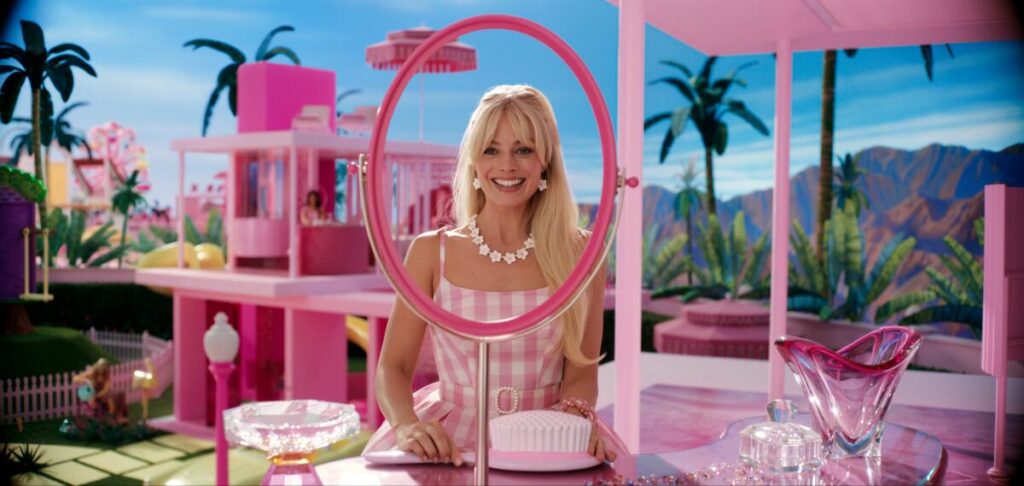

“It’s not an accurate resemblance to the thing you can buy in the shop, but it has the atmosphere and the character of it,” production designer Sarah Greenwood says of the Dreamhouse created for Barbie (Margot Robbie) in the film. “Greta [Gerwig] was clever [with the idea] that if we make a few things that are outsized, like the hairbrush, then the audience will come with us on the journey and then you start to believe it.”

(Warner Bros. Pictures)

“It was incredibly exciting — and then it was completely scary,” Greenwood says. “Now you look at it and you go, ‘Oh, that’s so simple.’ But it was actually the most difficult thing to arrive at visually. What was it? How was it going to work? What on Earth does a world like this look like? … Intellectually and philosophically it was one of the hardest films that we’ve ever done. I know it sounds mad, but it was.”

Greenwood and Spencer had a lot of conversations with Gerwig about the look of the film. They needed to understand what evoked the essence of a toy. Barbie wouldn’t use the stairs in her Dreamhouse because a kid would simply pick up the doll. There would be no walls or running water. The swimming pool, sea and sand would be plastic. Most importantly, the characters needed to feel believable within the world so that once Barbie and Ken (Ryan Gosling) arrived in the more mundane Los Angeles they seemed alien. That meant that Barbie Land had to be a newly imagined place that also felt familiar.

“It’s an interpretation,” Spencer says. “It’s not a pure reproduction of something. It’s not an accurate resemblance to the thing you can buy in the shop, but it has the atmosphere and the character of it. Greta was clever [with the idea] that if we make a few things that are outsized, like the hairbrush, then the audience will come with us on the journey and then you start to believe it. It’s a Brechtian theatrical thing.”

Greenwood and Spencer, who had never owned a Barbie themselves, bought a Dreamhouse for inspiration and looked at a recent book that compiled photographs of the various iterations of the Dreamhouse from the past 70 years. They drew from ‘80s design, but primarily focused on Midcentury style, which led them to Palm Springs, a major influence on the film’s visuals. As the design process progressed, several Barbie Land rules solidified: no black and white, no chrome, no electricity, no external elements like wind or sun. They looked at more than 100 shades of pink and eventually settled on the 12 that were used in the sets, as well as some of the costumes.

Production designer Sarah Greenwood, right, and set decorator Katie Spencer

(Tom Jamieson / For The Times)

“Everybody used the same palette. Our set for Barbie Land had to be very pure colors,” Greenwood says. “The great thing about shooting the real world in Los Angeles was that we then weren’t tied to a palette. The contrast between the real world and Barbie Land is quite extreme. It’s almost like L.A. is monochromatic next to the color of Barbie Land, but it’s not monochromatic at all.”

While the Barbie Land you see on-screen looks seamless, it took a few tricks to give the world scope. Greenwood and Spencer built four Dreamhouses, including the one Robbie’s Barbie lives in, on a London soundstage in front of an 800-foot-long, three-layered painted backdrop with the sky and mountains. The houses were designed in a pole-and-beam style and needed to be structurally sound, so the team constructed them from steel. They were also scaled up at 23%, which is the accurate proportion of a real Barbie doll to a Dreamhouse. The whole process of building the cul-de-sac took nearly five months.

“The thing that Greta wanted was as much in camera as possible,” Greenwood says. “So that it had that tangibility and toy-like quality. You’re creating a world that kids feel like they can go and touch. That became a key thing for us and that it’s not a big CGI fest. We know what that looks like and it could have easily fallen into that, but it was very carefully avoided.”

The establishing shots of Barbie Land and the shots of the row of shops along the boardwalk were created with miniatures. The VFX department then scanned the miniatures and stitched them all together, ensuring that the all-important toy quality was maintained in every scene. For the angular house where Weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon) lives, Greenwood looked to a variety of inspirations, including the hilltop house from “Psycho” and Antoni Gaudí.

“It was really magical because filmmaking takes you back to childhood and what you loved as a child,” Spencer says. “And the appeal of this is it really is like playing in your own toy box. In Barbie Land, it felt so real. The swimming pools were obviously plastic and paint, but people would still walk around them.”

Ryan Gosling, center, and the other Kens take Barbie’s Dreamhouse into over-the-top masculine territory.

(Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures/Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)

Later in the film, the Kens take over Barbie’s cul-de-sac, transforming the Dreamhouses into their own patriarchy-themed Mojo Dojo Casa Houses. Spencer redressed the existing sets to reflect the manly elements Gosling’s Ken has brought back from the Real World, including mini-fridges and leather furniture.

“The key thing was talking with Greta and saying, ‘Do you really mean this ugly?’” Spencer recalls. “And she said, ‘Absolutely.’ We were bringing these big La-Z-Boy black leather couches into a perfectly balanced, harmonious world. We had over 20 televisions playing the same footage of horses cantering. It was so much fun. Ken has seen all these things, like that men’s barbecue. So he brings in all these barbecues, but he doesn’t eat so he puts plastic food on the barbecue. We made all these books, like ‘Noble Steeds for Noble Men.’ What was so funny was that about 50% of the crew wanted the stuff from the Mojo Dojo house after the film, although I’m not going to say which 50%.”

These small details may not be noticeable on first viewing, but the specificity of the world was essential to making it immersive. The vehicles in the film, like Barbie’s car and the pop-up ambulance, were designed by Greenwood and Spencer and built by Picture Vehicles, which is based at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden. The same team also built the Batmobile, and Barbie’s car now sits in an archive alongside Batman’s famous ride. There was an entire department dedicated to decals, which were used on the cars, props and signage. For the Ken fight scene, a crew member handcrafted 24 hobby horses. The backdrop painted for the Mattel headquarters boardroom reveals a tweaked version of the L.A. skyline that you’d have to freeze frame to notice.

“There are nods to ‘The Wizard of Oz’ throughout the film: the pink brick road and ‘The Wizard of Oz’ is playing in the movie theater,” Greenwood says. “So the painted backdrop, right outside the window, has downtown Los Angeles as the Emerald City but in gold. There are all these things that are in there that are like Easter eggs. … What I loved about it was all this amazing talent across the board doing all of these amazing things. That was the beauty of it, so therefore that was the fun of it. And if it’s not fun why would you want to do it?”