Terry Gilliam has been to Cannes with three of his own films since 1983, but one of his favorite memories of the festival takes him back to that very first time, at the 36th edition, as the co-writer and co-star of Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. Along with Graham Chapman and the film’s director Terry Jones, he’d emerged from the Carlton hotel’s iconic entrance, then bedecked with promotion for the upcoming Bond movie Octopussy, to encounter a camera crew. Jones started grabbing people at random, shouting, “WHO EES MONTY PYTHON???” in a ridiculous foreign accent, and got so carried away that, when they reached the hotel’s famous terrace, he accidentally did it to Gilliam too.

The crowd loved it, and the day only grew stranger. Out on the Carlton’s jetty, they gave an interview to British news channel ITN, with Jones hiding behind Graham Chapman’s back while Gilliam ate After Eight mints from the box. Chapman deferred every question to Jones, who finally insisted that the film was made for the benefit of the world’s fish population. Why? “Well, we’re trying to achieve the widest possible audience,” he explained. “There are huge shoals of fish in the ocean, and we thought that if we could break through to that kind of audience, we’d be onto a money spinner, didn’t we?”

Here they were, at the film festival where Bergman, Fellini and Kurosawa were revered as gods, with a film that even fellow Python member Eric Idle described as “gross”, “nasty”, “violent”, and “unnecessarily grotesque”. The experience, the night before, of a black-tie audience watching the Citizen Kane of gross-out comedy had been indelible. But the moment that registered the most strongly with Gilliam was completely left-field.

From left, Liza Minnelli, Jerry Lewis and Sophia Loren at the Cannes Film Festival in 1983.

Micheline Pelletier/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

“In the midst of all this,” said Gilliam, “suddenly I could feel this heat on my back. It was like the sun was burning, it was really hot. I turned around, and [there] was Jerry Lewis, beet-red, staring, just angry because we were in his way. We were in France and the camera was interested in us, and he hated us. It was just a great moment. I could actually feel the heat coming off of this man; this face was ugly, so full of hatred. It was amazing!”

Though a respected comedian in his native America, Jerry Lewis, a man never famed for his magnanimity, was used to nothing less than worship from the French, even claiming, with typical humility shortly before he died in 2017, that, on a recent visit, French newspaper Le Figaro had plastered his face on the front page, with a headline that roared, “THE KING IS HOME!” When the Pythons arrived in Cannes, Lewis had just opened the festival in the world premiere of Martin Scorsese’s film The King of Comedy, in a ceremony attended by Liza Minnelli, Charlotte Rampling and Sophia Loren.

Scorsese’s film showed a new side to Lewis, playing obnoxious chat-show host Jerry Langford alongside Robert De Niro as aspiring stand-up Rupert Pupkin. Despite the title, it was very much not a comedy, more a scathing satire on the dark turn that American TV was taking in a new era of celebrity culture. And, besides, no one was really expecting it to be a comedy anyway, since nothing laugh-out-loud funny had ever won a Palme d’Or since the festival began, with the arguable exception of Richard Lester’s Swinging London caper The Knack… And How to Get It, which took one home in 1965.

Lewis may have thought he was a shoo-in for Best Actor, especially with 1979 Palme d’Or winner Scorsese returning to the event for the first time since Taxi Driver and American author William Styron (Sophie’s Choice) heading the jury. But The King of Comedy — like Martin Ritt’s period romance Cross Creek and Bruce Beresford’s C&W drama Tender Mercies — didn’t win anything; according to Gilles Jacob, then artistic director of the festival, it was the first time U.S. films had been shut out since 1969.

Eric Idle and John Cleese in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Everett Collection

The Palme eventually went to Shōhei Imamura’s The Ballad of Narayama, but there had apparently been surprisingly little consensus amongst the jury. In fact, when it came down to presenting Best Director they opted for a split vote, tying Andrei Tarkovsky (for his minimalist classic Nostalgia) with Robert Bresson (for his minimalist classic L’Argent). “It came down,” said one French critic, “to the pro-Bresson party versus the anti-Bresson party”). Tensions ran so high that when Orson Welles announced the result, Bresson was booed and accepted his award in suitably Bressonian silence.

The jury was united on one thing, however. The winner of the Grand Prix, an award introduced in 1967 and now effectively the second prize, was a hit with a diverse jury that included French journalist Yvonne Baby, Egypt’s Youssef Chahine, Mali’s Souleyman Cissé and the Soviet Union’s Sergei Bondarchuk. And so it was that the Pythons’ Terry Jones returned to the Croisette and ascended the steps of the Bunker to pick up the award from one of the night’s surprise presenters: a very, very bemused James Mason.

In case anyone needs an introduction to theaforementioned Gilliam, Jones, Chapman and Idle, these four — along with John Cleese and Michael Palin — were the brains behind the influential late-night British sketch show Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which debuted on the BBC in 1969. The Pythons, as they came to be known, pioneered surreal, non-sequitur comedy that threw away the rules about set-ups and punchlines. For example, in a 1971 sketch, called “The Pantomime Horse Is a Secret Agent,” a British spy in a horse outfit pursues a Russian spy in a horse outfit (both on bicycles), only to be ambushed by the Royal Family’s Princess Margaret and a goose. Luckily, he is saved: by a regimental sergeant major, the playwright Terence Rattigan, and the Duke of Kent.

The show was a cult hit in the U.K., but, understandably, even the Pythons themselves thought that would be the extent of it. “We never thought it would go to America,” Cleese later recalled. One of the main problems was expense: the BBC shows were filmed in PAL and would have to be transferred to the NTSC format. So, to introduce them to the U.S. market, Victor Lownes, head of Playboy U.K. asked for help from his boss Hugh Hefner to put together a calling-card film, to be distributed by Columbia-Warner Bros.

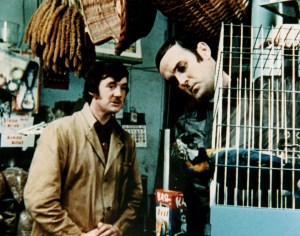

The result was a big-screen compilation of the BBC show’s greatest hits, helmed in a TV way by its director Ian McNaughton, called And Now for Something Completely Different. In an act of recycling unthinkable today, it recreated skits such as “The Dead Parrot”, in which a pet shop owner brazenly denies having sold a customer a deceased Norwegian Blue, even though it is stiff as a board and nailed to its perch. There was also “The Funniest Joke in the World,” in which the British army translates a killer gag into German to win the Second World War. And let’s not forget “Self-Defense Against Fresh Fruit”, in a which a weary group of would-be vigilantes turn against their fruit-obsessed instructor, sighing, “We’ve DONE apples, oranges, grapefruits — whole and segments.”

Michael Palin and John Cleese in And Now For Something Completely Different.

Everett Collection

The film flopped, but the Pythons weren’t surprised. After all, it was simply a rerun of old skits with no linking device, and the members of group felt there hadn’t been enough consultation with them, a key part of their creative process. But it was enough to kick-start the growth of the Pythons’ reputation in the U.S., and in 1974 a soft launch on KERA-TV, a PBS station in Dallas, did what the film couldn’t do; by 1975 Flying Circus was a word-of-mouth hit, airing on other PBS stations in the most populated states.

The time was right for the Pythons to take things up a notch with another, proper movie, but at home, the British film industry was in a moribund state, largely dominated by the conservative Rank Organization, by then a shadow of its former self. In lieu of a studio, a Python associate had the bright idea of tapping the world of rock’n’roll for cash, raising a projected budget of somewhere between £150,000 and £200,000. The likes of Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, record label Charisma Records — the home of Genesis — and some rumors say even Elton John chipped in, with no strings attached. All respected their fellow artists’ need for autonomy, while perhaps also hoping to write their investments off at a time when income tax in the U.K. was running as high as 90%.

The first draft of that script was very much a work in progress, featuring a story that began in the Middle Ages and ended in the 20th Century, with a nerdy man called Arthur King finding the Holy Grail in the grail section of London department store Harrods. Terry Jones, a history buff, persuaded the team to focus on the Middle Ages, so they all went away to research the period. Jones, by this time, was itching to direct, as was Gilliam, so they agreed to co-direct. Both had very different thoughts and looks (Jones went for a hand-held style, Gilliam for something artier, with lots of smoke), but both were inspired by the earthy arthouse films of Italian auteur Pier Paulo Pasolini.

Although it went through 13 edits and a complete change of score, Holy Grail was a game-changer, being a lean, 90-minute narrative film in which the fabled British King Arthur (Chapman) tours the U.K. looking for knights to join him on his Round Table. Along the way, he gets a mission from God to find the religious relic of the title, only to find that rival French nobleman Guy de Lombard has already got one (“It’s verry niiice”).

The film was scrappy but well-received in the U.S., especially by superfan Elvis Presley, who is said to have screened the film over 45 times at his private cinema in Graceland. More significantly, it paved the way for the Pythons’ biggest and most successful film of all: Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), a historical romp in which Chapman played the title character, the next-door neighbor of Jesus Christ, who is mistaken for the Messiah.

Though all concerned were into middle age by then, the film was as scandalous as the wave of punk rock that had shaken up the music industry a few years earlier. The financier this time was a musician with bigger pockets than the ones before: George Harrison of The Beatles, who’d read the script, fell out of bed laughing, and re-mortgaged his house to fund the film after a nervous EMI, who distributed Holy Grail in the U.K., pulled out (“I wanted to see the film,” he reasoned, quite reasonably).

From left, Eric Idle and Terry Jones in Life of Brian.

Orion/Everett Collection

Although the film makes it very clear that Brian is merely a supporting player in the life of Jesus Christ, the religious right refused to see it that way. Said Michael Palin, “We were most surprised by the extent of the backlash, especially in America; people were actually carrying banners outside the theater — there were nuns with banners! It was just the best thing that could possibly have happened in retrospect, but at the time I couldn’t believe that people would react like that.” It soon transpired that most of the film’s most vociferous critics hadn’t actually bothered to watch it. Jones cited the example of a U.K. councilor in Devon, who happily admitted that he’d voted to ban it sight unseen. “You don’t need to go near a pigsty,” he’d said, “to know that it stinks.”

These attempts to stifle it only fanned the flames, and, indeed, nearly half a century later, the film’s longevity speaks for itself. For one thing, the film’s closing song, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” — sung by Eric Idle, hanging alongside Brian on a cross — has only recently dropped out of the top 10 most-requested songs at funerals in the U.K.

Luckily for George Harrison, all this controversy not only made Life of Brian a hit, it bankrolled his production company, Handmade Films, for a decade, producing ’80s films such as The Long Good Friday, Time Bandits, Mona Lisa, and Withnail and I, all future cult classics that didn’t quite find their audiences when they needed them. But for the Pythons, Life of Brian was about to become an albatross; the industry was expecting a follow-up, but the once tight-knit group had already started to dissemble, notably when Cleese quit their TV show to develop his sitcom Fawlty Towers, which debuted in 1975.

Though there were personality clashes within the group, Cleese had stayed on friendly terms with the Pythons, continuing to contribute as a writer and joining them for their four-night stint at LA’s Hollywood Bowl in 1980. But after Fawlty Towers became a hit, it was clear that camaraderie alone would not carry the day. Cleese, already tired of having to submit his ideas for group discussion, now wanted guarantees of financial stability, so his ears pricked up when the Pythons’ then-manager, Dennis O’Brien (Harrison’s partner in Handmade), told them that if they moved fast on a new movie project they would “never have to work again”. “That was a nice prospect,” Cleese said. “But for that reason, and that reason alone, we sat down to start writing the next movie without having a fallow period, which I think would have been much better.”

The Pythons subsequently parted ways with O’Brien, which made another film with Handmade untenable. Luckily, Universal was happy to step in, even though they were told they couldn’t see the script and had to pay $8 million for it. All they saw was a poem, penned by Idle, that began: “There’s everything in this movie / There’s everything that fits / From the meaning of life and the universe / To girls with great big tits…”

But when the group set off to the West Indies to pool their ideas, it soon became clear that there was nothing to hold it all together; Jones had a vague idea about World War III, while Cleese and Chapman had come up with a scenario about a mad ayatollah. On the flight over, Jones was nervous. “I remember thinking, This just isn’t getting anywhere,” he later said, “and I woke up with a tight knot in my stomach like you get at exam time at school. I had a look at what I had and found I’d packed a script which our continuity lady had. I looked through it and realized we had about 70 minutes of material which we [Jones and Palin] thought was fantastic… I said, ‘What are we all worrying about? We’ve got 70 minutes of great material, so we’ve only got to write 20 minutes — surely we can do that? All we’ve got to do is get the structure.’”

Cleese had been all for just giving up and enjoying the sun, but then someone suggested “The Seven Ages of Man” as a framing device, citing the famous quote from Shakespeare’s As You Like It: “All the world’s a stage / And all the men and women merely players / They have their exits and their entrances / And one man in his time plays many parts / His acts being seven ages.” Hearing that, Idle revived The Meaning of Life as the title, and the approval was unanimous. But, deep down, the Pythons knew it was a step backwards, a return to the sketch comedy they’d tried so hard to escape.

Loosely inspired by Spanish-Mexican Surrealist director Luis Buñuel, The Meaning of Life starts in a hospital delivery room and ends with the cast reunited for a Christmas party in the afterlife — an RKO-style song-and-dance number led by Chapman’s flamboyant emcee. In between, the film had some of their most famous moments; notably, two great musical set-pieces — the Catholic singalong anthem “Every Sperm is Sacred”, and the cheerfully nihilistic “Galaxy Song”, which concludes that we should all “Pray that there’s intelligent life somewhere up in space / ’Cause there’s bugger all here on Earth”.

Terry Jones as Mr. Creosote in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life.

Everett Collection

More notoriously, there was the still-nauseating “Mr. Creosote” sketch, in which a rich, rude, and obscenely fat man (Terry Jones) explodes in a swanky restaurant after eating a single “waffer-thin” mint, covering his fellow diners in a graphic rain of vomit and guts. (Quentin Tarantino has since said, “I still can’t think about that scene without retching.”)

But the Pythons knew they could, should, and might have done better. “I felt I’d been forced into doing stuff I didn’t want to do anymore,” Gilliam said. “I didn’t feel we were working that well, although Jamaica was fun. Those were the best parts, just going off to write, because I think we had more fun sitting, eating and talking than doing the film.”

By the time The Meaning of Life was finally finished, the various members of the group had all successfully begun to flex their non-Python identities; Gilliam, Idle and Jones had ambitions in film, Palin in television (both fiction and documentary), and Chapman in literature, after publishing his candid memoir, A Liar’s Autobiography, in 1980. None were at all surprised, therefore, when Cleese chose not to join them on the Croisette. (“I’ve never been to the Cannes Film Festival,” he said later, “and I’m really proud of that. I can’t imagine anything more tedious”).

Nevertheless, they enjoyed themselves in his absence and basked in all the attention, which seemed to surprise them. Gilliam was especially taken aback when American filmmaker Henry Jaglom, whose film Can She Bake a Cherry Pie? was screening in Un Certain Regard, told him it was “the best thing Python had ever done”. Gilliam replied, “There’s great bits in there, but there’s crap as well,” but Jaglom didn’t bat an eyelid. “That’s why it’s great.” he said, “Because the crap is there to balance the greatness.”

Read the digital edition of Deadline’s Disruptors/Cannes magazine here.

Needless to say, winning the Grand Prix was not on anyone’s radar; at the beginning of the festival, Jones even joked at their press conference that they’d slipped payola to the festival, leading to the headline “PYTHON BRIBES JURY”. Returning solo for the closing ceremony to pick up the award, wearing a velvet dinner jacket with the words “EAT MORE PORK” emblazoned on the back, he kept up the joke, saying that the cash was stashed in the bathroom, under the pipes. In retrospect, though, the film’s cynical view of humanity now seems more Cannes-friendly than it might have then, anticipating the works of Yorgos Lanthimos, Ruben Östlund and, at a push, Michael Haneke.

Though much appreciated, the award came too late to be treasured, since, by then, the moment had passed, and it was clear there would nothing more from that well. Monty Python never actually officially disbanded, but when Chapman died in 1989, at the age of just 48, the reality could no longer be ignored.

On reflection, those few days in Cannes can be seen as a wrap party for the Pythons in the most final and literal sense.

“I felt it was over after The Meaning of Life,” said Gilliam, citing the film’s sparkly, joyous and now rather poignant celestial climax. “We all get to heaven, don’t we?”

Acknowledgments: Bob McCabe, The Pythons’ Autobiography by The Pythons (Orion); David Morgan, Monty Python Speaks (HarperCollins).