In December 2021, a band called Panchiko played a gig. Hundreds of fans were there, at Metronome in Nottingham, England, singing along to their songs. All of this might seem like a standard routine for bands, but for the three members of Panchiko, it was a marvel. “Having a show where people have paid their money and they really want to see us is really nice,” says Owain Davies, 40, who plays guitar in the band.

“People knew the words to the songs, which is crazy,” says Andrew Wright, 40, who also plays guitar.

Davies remarked on the joy of making eye contact with people at a gig like that. “When you play to nobody” – which they had done – “if you make eye contact with someone in the bar, they might not want to meet your gaze,” he says with a laugh.

The last time Panchiko played a show was 20 years prior, in 2001, at a festival in a tiny town called Sutton-in-Ashfield, and there wasn’t much meaningful eye contact. Wright said they played “to people milling about, buying a hotdog and staring at you weirdly”.

Panchiko disbanded not long after the 2001 show. The band members spoke occasionally but didn’t see each other often – mostly at friends’ weddings – until an internet mystery unexpectedly brought them back together in 2021. “It felt quite unbelievable then,” says Wright. “And I think the following has kind of grown exponentially even since then, and it feels even more unbelievable now, to be honest.”

In 2016, someone found Panchiko’s 2000 CD, titled D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L, at a thrift store in the UK, but was unable to track down any information about them online. They posted to 4chan asking for help. From there, the songs and the search for their provenance spread online, “on Reddit forums, Discord channels, private chats and YouTube”, according to a Vice article on the global effort to find Panchiko. It took four years before Davies, Wright and Shaun Ferreday, 40, who plays bass in the band, finally learned a dedicated group of internet sleuths were desperately searching for them.

Shocked that they suddenly had fans wanting to hear their old band, the members of Panchiko gradually began to put more songs on Bandcamp, then Spotify, and then later on cassettes, vinyl and, of course, CDs. They started with D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L and then began adding more. Davies had been keeping much of their music on CDs and minidiscs carefully tucked away in wallets for years (despite no longer owning a CD player), but there were some songs they had recorded that none of the band members even had any more – they had to ask around to see if any friends had them. “We had all this stuff and then there was an audience,” Davies says. “And then we weren’t having to make the stuff, we were just sort of finding things and presenting it to them: ‘Here you go, here’s something we did 20 years ago.’”

D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L, despite its name, is not death metal. The Panchiko song that inspired the album title was written in the late 90s, when nu-metal was enjoying mainstream success. The song, which opens the album, is gorgeously mellow with clear trip-hop influences. Warped strings glide by easily, punctuated by chopped-up spoken word samples, a looped melody played by keyboard chimes and electronic beeps. It’s gently moody with earnest vocals, conjuring a calmer version of Broadcast or Tricky. They hoped the mismatched title would be clever. “It seemed a good idea at the time to give it a title that would be the complete opposite of what was going to come out of the speakers,” says Davies.

Some of the earliest versions of Panchiko songs floating around the internet were ripped from the thrift store CD, which had begun to rot. Fans liked the added sound of the distortion. Panchiko have now included those versions on re-releases of the music, under titles like D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L_R>O>T.

Now they’re working on recording a new album and preparing for a US tour beginning in October, which is already partly sold out.

A few years before Panchiko recorded their first music, a band called Visual Purple was also going through a similar process in Canton, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit. Like Panchiko, Visual Purple broke up not long after recording their album, and now have also found a new following decades later. One key difference: the three members of Visual Purple were only 11 years old.

“We just did it because it was fun,” says Kevin McGorey, now 37, the lead singer and guitarist for Visual Purple. “It was just kind of innocent. There was no self-consciousness to it at all.” At the time, he wasn’t thinking that in 26 years, his tapes would be selling out in multiple rounds of releases on Bandcamp. K Records, the label founded by the Beat Happening frontman, Calvin Johnson, and whose logo was tattooed on Kurt Cobain’s arm, also distributed copies of the album, which immediately sold out.

K Records posted on Instagram about the album, “and people were kind of freaking out”, says Shelley Salant, a musician who runs a record label called Ginkgo Records, which released the Visual Purple tape in March of this year. “You know, I see why people are freaking out. It’s really good. And it’s kind of amazing that it was made by an 11-year-old.”

By the time they recorded their self-titled album, McGorey had already been playing guitar for two years. In third or fourth grade, he brought a guitar to school to play Lola for his class (“I was really into the Kinks,” McGorey says). His dad, Chris McGorey, said his teacher enjoyed it so much, he brought McGorey to the teachers’ lounge to do an encore for the faculty.

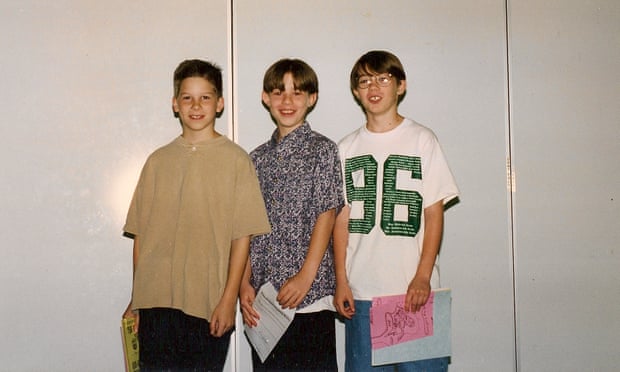

Visual Purple was McGorey’s first band, with his friends Paul Rambo on bass and Matt Carlson on drums, and their biggest gigs were at the sixth-grade talent show and their Dare graduation ceremony (a photo of the Dare show serves as the cover image for the album), where they played nearly all original songs except for Pink Floyd’s Another Brick in the Wall (which one teacher tried to cut off, due to the anti-education lyrics, McGorey’s dad says).

“I thought they were very original,” says Chris McGorey, a musician himself. Chris McGorey, who describes himself as “the George Martin for Visual Purple”, recorded the trio in 1996 with “one decent mic” and the four-track tape recorder he had previously used for his own projects. “I was extremely impressed that they were writing all their own material,” he says. “It was a raucous, joyful sound. Kevin was belting out vocals with no filter, straight from the pre-adolescent heart!”

In 2016, McGorey’s dad dug out the tapes (“I’m one of those people who keeps everything, in the hope that it might be able to be unleashed upon the world, at some point in time,” he says) and gave them to him. Then in 2020, during the pandemic, McGorey decided to put the songs on YouTube. Sallant, a friend of McGorey’s, heard them and had the idea to release them as cassettes. There was no Visual Purple reunion gig tied to the release (McGorey still plays music professionally in Detroit, but Rambo and Carlson have moved away), but internet buzz spread, including a recommendation by Cryptophasia, a music newsletter written by Jenn and Liz Pelly, twin sisters and music journalists in New York City. The Pellys described Visual Purple’s music as “outrageously sick raw noise pop”.

Visual Purple’s name and album title are a reference to Bill Nye the Science Guy, and the song titles are straightforward topics: Ghost, Sneakers, Fur Coat. On Glue, a wistful pop song reminiscent of Guided By Voices (a fact observed on the Bandcamp page description), McGorey describes a predicament: “I was just fooling around, but now I’m stuck with this glue / Glue is all over me / Glue get it off of me.” Noise, a song about the band itself and an irritated neighbor, starts strong with an intriguing melody on slightly warped guitar, before picking up speed with swishy drums and layers of grungy guitars. It sounds like it could fit comfortably on C86, the 1986 NME compilation that represented a pivotal moment in indie music.

Visual Purple’s album is slated for another cassette drop and may eventually see a vinyl release as well. But there’s no additional material coming – this was their one and only recording. “It’s not like they have another secret album,” Sallant says. But McGorey has been playing music continuously in the decades since Visual Purple disbanded, most recently releasing songs under the name Vinny Moonshine, on a label called Metaphysical Powers. And he’s gained inspiration for his current music career from releasing his oldest material. “People’s reactions to it seem to be genuine joy, so I like that,” McGorey says.

For the members of Panchiko, there’s a similar sense of revelation that has come from connecting with fans in a way that would not have been possible when their music was originally released. “I think we’ve got more of a connection with the fans,” says Ferreday. “Before, we had no connection with the fans. We didn’t even know they were there. Because we know they’re there and we talk to them all the time, you care more.”

“It’s a position that loads of people in bands would kill to be in,” says Wright. “And we don’t want to mess it up.”

“We still realize it’s a privilege,” says Davies. “And we owe so much to these people who invest their time in liking what we do.”