Vince Guaraldi’s career, or rather the legacy of his career, is a curious thing. His name is absent from the index of Ted Gioia’s authoritative The History of Jazz. Nor was it mentioned, even in passing, during the 19 hours of Ken Burns’ documentary series Jazz. When the great jazz critic Nat Hentoff belatedly wrote an essay about him in 2010 – 34 years after Guaraldi’s sudden death, aged 47 – it was in the context of rediscovering a lost figure, noting that Guaraldi had never been on the list of nominees for the Jazz Hall of Fame, and comparing him to the largely forgotten swing-era trombonist Jack Jenney.

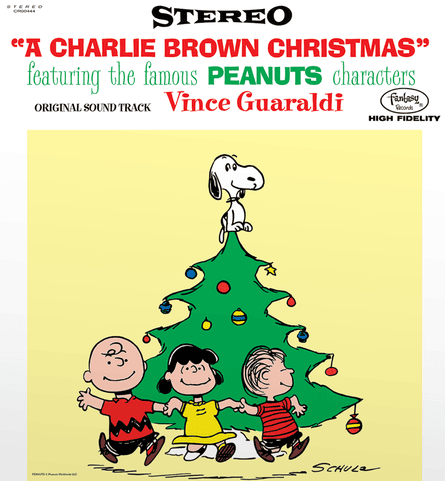

Like Jenney, Guaraldi died young, and, like Jenney, he played with a succession of names more likely to crop up in jazz history books and documentaries than his own: in Guaraldi’s case, Stan Getz, Ben Webster and Woody Herman. But that is where the similarities end. Guaraldi’s early death notwithstanding, his career is hardly a case of what-ifs. He was an expansive, even boundary-breaking artist: around the time Miles Davis was attempting to widen his audience by sharing bills with Neil Young and appearing at the 1970 Isle of Wight festival, Guaraldi was up on stage in San Francisco, jamming with Jerry Garcia; he also had a fair claim to be the artist who did the most to introduce young audiences to jazz during the 60s and 70s. He saw – and continues to see – vast commercial success: 1962’s Cast Your Fate to the Wind was, alongside Dave Brubeck’s Take Five, one of the few jazz hits of the era; 1965’s A Charlie Brown Christmas is one of the bestselling jazz albums of all time, alongside Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue.

You suspect the problem for jazz historians is that said album was the soundtrack to a children’s cartoon, albeit a children’s cartoon of a very particular stripe. A Charlie Brown Christmas was commissioned by the Coca-Cola Company. They presumably weren’t expecting Charles M Schulz to write a script about the money-grubbing commercialisation of Christmas and the depression wreaked by festivities that never quite live up to your expectations, one whose plot turns on a lengthy reading from the Gospel of Luke in the 1611 King James translation. Certainly, executives at the CBS network were horrified: at its pace, its simple animation, Shulz’s refusal to include the then ubiquitous canned laughter, and at Guaraldi’s soundtrack.

There are funny scenes in A Charlie Brown Christmas, but the whole 25 minutes is shot through with a haunting vein of melancholy, which Guaraldi picked up on and amplified in his score. Effectively its theme song, Christmas Time Is Here rests on moody minor chords, undercutting the hopeful lyrical message that’s sung by a slightly off-key children’s choir. One of Guaraldi’s masterstrokes was to insist on recording the choir with imperfections intact, to match the cartoon itself – the characters were voiced not by actors, but ordinary children, a daring move for the time – so that the vocal tracks recall a school nativity play or carol concert. The instrumental version feels like a long, depleted exhalation, compounded by Guaraldi’s piano frequently playing just behind the beat. Something faintly ominous lurks in the background of its adaptation of Little Drummer Boy, My Little Drum. What Child Is This is based around the sweet but sad melody of Greensleeves, while the version of O Tannenbaum opens with Guaraldi playing the melody alone at the piano, his performance filled with pauses. It seems to express more hesitancy about the festive season than a wholehearted embrace.

It’s not all yearning and tristesse. Christmas Is Coming propels itself along, accurately drawing a picture of anticipation; Skating is straightforwardly sublime, its melody descending in flurries. Perhaps that’s the reason for A Charlie Brown Christmas’s longevity, and indeed the reason there’s a market for yet another deluxe edition – seemingly an annual occurrence at this point – which packs out four CDs with enough alternative takes to satisfy even the most obsessive fan. It never touches the sonic cliches of Christmas music, and manages to convey the complete range of emotions you might feel about the season. There’s not a sleighbell to be heard.

There’s no doubt the Charlie Brown soundtracks overshadowed the rest of Guaraldi’s career: the vast majority of his oeuvre isn’t on streaming services, and on the cover of the 2009 compilation The Definitive Vince Guaraldi – which delays breaking out Charlie Brown until CD 2, devoting the first to Guaraldi’s experiments with Latin American music – he’s pictured alongside Charlie Brown’s piano-playing chum Schroeder. Clearly, he didn’t mind: he carried on scoring Charlie Brown cartoons for the rest of his life, shifting towards synthesisers and a vaguely fusion-inspired sound as he went. As a side-effect, he secured prime-time exposure for jazz in an era when most jazz artists would have struggled to get anywhere near prime-time television. Guaraldi probably deserves more shine in jazz histories on that basis alone. Then again, once a year, his star burns brighter than any of his peers: like the cartoon it soundtracks, A Charlie Brown Christmas is a low-key masterpiece.

This week Alexis listened to

Sam Gendel: I Swear

From Gendel’s forthcoming album reinterpreting 90s and early-00s R&B, this is All-4-One’s Mellow Magic classic turned into a ghostly reverie, the melody played on … a theremin? A bowed saw? A synth? Impossible to say, but the results are shiver-inducing.