Book Review

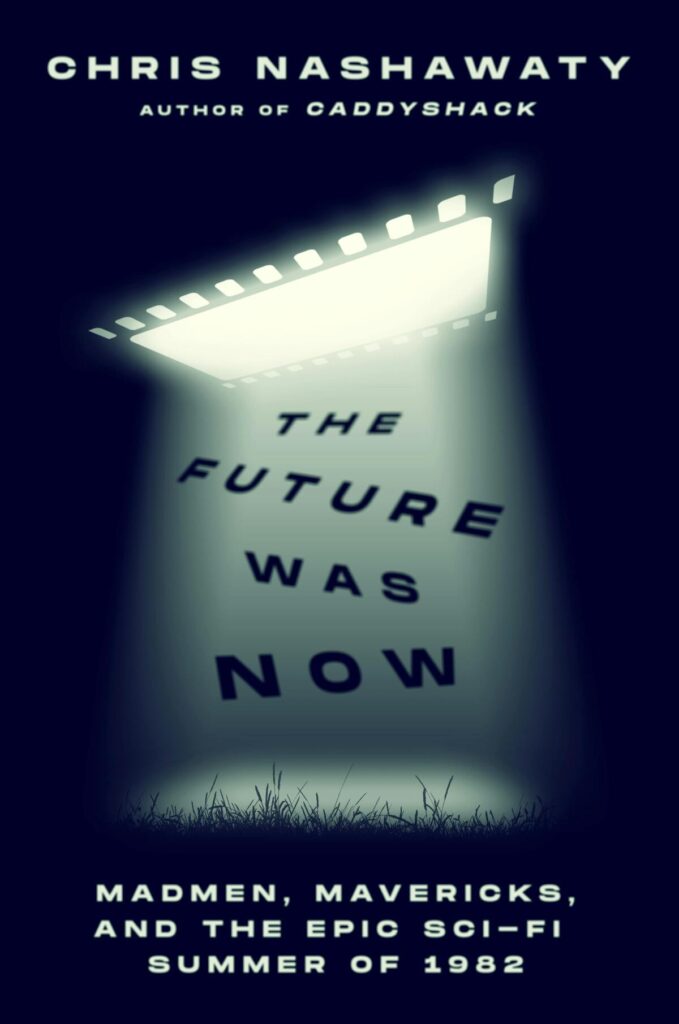

The Future Was Now: Madmen, Mavericks, and the Epic Sci-Fi Summer of 1982

By Chris Nashawaty

Flatiron Books: 304 pages, $29.99

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There was a time, not a long time ago or in a galaxy far, far away, when the summer movie landscape wasn’t overcrowded with disposable fantasy and sci-fi tentpoles. When studios and distributors hadn’t yet been trained to put all of their eggs in a shrinking collection of threadbare baskets. “Four-plus decades ago,” as Chris Nashawaty writes in his new book “The Future Was Now,” “we were entertained, enthralled, and delighted. Today, we’re merely cudgeled into numb submission over and over again and treated like children being spoon-fed the same sound-and-fury pap.”

Nashawaty’s book zooms in on a specific period — the summer of 1982 — that he posits as both a peak flowering and a last hurrah of the sci-fi genre as serious, ambitious and original popular art. Taking an envious look at the unexpected, unparalleled and lucrative frenzy over “Star Wars” (1977), movie executives asked themselves the question that movie executives are so good at asking, if not necessarily answering: How can we make something just like that (or, at least, something that rakes in similarly obscene gobs of cash)?

Much as the previous decade’s execs drooled over the returns on “Easy Rider,” “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Graduate,” this bunch sought to put their energies and resources into movies the kids would like, even if this generation was more enthralled with escape than revolution.

As Nashawaty writes, “The only problem was that all the studios seemed to learn the exact same lesson at the exact same time.” “The Future Was Now” sprints through the making and reception of eight movies that Nashawaty files under the sci-fi rubric, all of which somehow invaded theaters within the same two-month span. “Blade Runner,” “Conan the Barbarian,” “E.T. the Extraterrestrial,” “Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior,” “Poltergeist,” “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan,” “The Thing” and “Tron”: They vied for moviegoers’ attention and disposable income. This was a glut that couldn’t be sustained. What would studios learn from this?

It’s a promising premise, and “The Future Was Now” has no shortage of juicy storylines. There’s the case of Steven Spielberg, who had already made a classic sci-fi film, “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” and who had two projects ready to start filming at the same time: the optimistic “E.T.” and the terrifying “Poltergeist.”

Because the Directors Guild of America had explicit rules against directing two movies at once, Spielberg had to find someone else to helm “Poltergeist.” He chose Tobe Hooper, who had made his scary bones with “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.” Then, by many accounts, Spielberg ended up all but directing “Poltergeist” over Hooper’s shoulder.

Like the rest of the book, this episode is thoroughly reported; Nashawaty was able to speak with many of the people he writes about here, including Spielberg.

Not all of these 1982 summer movies were hits, and some of their directors paid a steep price for their part in the eight-movie pileup.

Ridley Scott, coming off the success of his outer space horror movie “Alien” (the making of which is lovingly detailed here), clashed with his “Blade Runner” star, Harrison Ford; his crew, much of which deemed him a dictator; and executive producers who took over the movie in postproduction. Chastened, Scott beat a temporary retreat back to his advertising career.

Meanwhile, John Carpenter fared even worse when “The Thing” was met with indifference by audiences and outright hostility by critics. His multi-picture deal with Universal was torn up, and his career never fully recovered. “I was treated like slime,” he tells Nashawaty.

There’s a whole lot going on in “The Future Was Now” — at times, too much. A study of eight movies will almost by definition be diffuse, and it sometimes feels like Nashawaty is just starting to get to the heart of one subject when he feels compelled to move on to the next. Nashawaty’s passion for this story is clear, but it also gets diluted by the necessity to serve so many masters.

The author is not just a good reporter, but also an excellent and thoughtful critic, and the book’s breakneck pace underserves this skill set. I wanted more on what this fine cinematic thinker feels when he watches these movies; though this isn’t intended to be the book’s focus, a little more of Nashawaty’s voice would have gone a long way.

That said, major books that deal with movies thematically are now few and far between, and “The Future Was Now” is a welcome addition to the catalog. Beneath the blow-by-blow is a story about the turbocharging and selling of fan culture, both its charms and its discontents (which, come to think of it, could make a great book in itself).

For Nashawaty, the summer of ’82 was a hinge moment, after the “Star Wars” big bang and before the studios turned blockbusters into widgets. He writes: “By the dawn of the ’90s … what should have been a new golden age of sci-fi and fantasy cinema became a pop-culture beast that would devour itself to death and infantilize its audience in the process.” And the results are still coming to a theater near you.

Chris Vognar is a freelance culture writer.