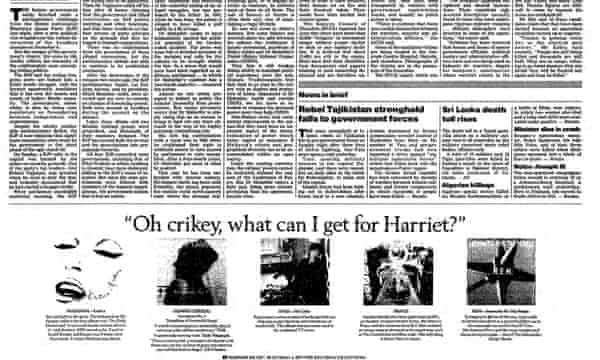

“Oh crikey, what can I get for Harriet?” asked an ad in this newspaper three days before Christmas 1992. Alongside images of albums by Enya, Prince, Madonna and REM was one featuring the silhouette of a praying woman and a little-known name not usually featured alongside these multimillion selling artists: Henryk Górecki.

The album in question featured a recording of Górecki’s Symphony No 3, Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, a 55-minute work for orchestra and soprano written in 1976. Its three movements, all slow, set Polish texts that reflect on motherhood, religion and death, including a prayer that was inscribed on a wall in the Gestapo’s headquarters in Zakopane by an 18-year-old female prisoner.

Unsurprisingly, the recording did not start life intending to keep the company of Madonna and Prince – but in late 1992 the symphony was soaring high. For 11 weeks it was among the 40 bestselling albums in the UK, peaking at No 6 in early February 1993, in between Paul McCartney’s Off the Ground and REM’s Automatic for the People. It topped the classical charts on both sides of the Atlantic, and total sales today have surpassed 1m – an unthinkable and still unique figure in contemporary classical music. Thirty years on from its April 1992 release, the album’s ascent is the stuff of legend.

Górecki, born in 1933, started out writing dissonant, complex and uncommercial music, as was expected of avant-garde composers at the time. His change of heart in the mid-70s – towards a simpler, more spiritually inclined style – was not a ploy to hit the mainstream. In fact, this shift simply alienated him from his peers: the Third Symphony was a flop on its 1977 premiere. But in 1985, David Drew of the music publishers Boosey & Hawkes chanced upon Górecki at a Warsaw music festival. Back home, he listened, rapt, to an early Polish recording of the Third Symphony.

Thanks to Drew’s enthusiasm, in 1989 the London Sinfonietta organised a weekend-long concert series featuring music by both Górecki and the Soviet composer Alfred Schnittke. Robert Hurwitz, then president of the US label Nonesuch (part of the Warner stable), flew over for the weekend. He too had already heard and enjoyed a recording of the Third Symphony – and, considering that version “perfectly fine”, had no plans to record it again. He was more interested in other works on the bill: “The Third Symphony was kind of a bonus for the weekend,” he says.

An overwhelmingly powerful live performance – the work’s London premiere – with the soprano Margaret Field and conducted by David Atherton, changed his mind. The critics agreed.

“The most imposing work [of the programmes] was Górecki’s Symphony No 3, which drew together many strands in his musical personality. An impressive individual musical statement,” wrote the Guardian’s Meirion Bowen. “The astonishing Third Symphony … at almost an hour of very slow music, could have become a trial, and for some it evidently did. I can only say that I found it made an intensely physical impact, with its relentless tread and its piercingly simple melodic lines,” wrote Nicholas Kenyon in the Observer.

“It really did feel like a major event,” says Janis Susskind, who has worked at Boosey for 40 years and is now managing director. “You could just see the planets coming into alignment, that there was potential for getting this remarkable symphony to a bigger audience.”

Nonesuch’s subsequent recording featured the Sinfonietta (which, as was the norm for such projects, was paid a one-off fee rather than receiving royalties), with the conductor David Zinman and the emerging US soprano Dawn Upshaw, whose piercingly pure vocal tone contrasted with earlier renditions.

“After the sessions, I thought: ‘This is better than I anticipated,’” Hurwitz recalls. “‘I think it could be a success; we might even sell 25,000 copies.’”

That the album went on to sell 40 times that number was way beyond the dreams of anyone involved. The then new commercial radio station Classic FM helped play a part. It had launched in September 1992 and immediately put the symphony’s shortest movement, the second, on heavy rotation. The recording touched a nerve.

“Suddenly it was reaching music lovers and listeners, jumping over the heads of the gatekeepers,” says Susskind. “It was thrilling, actually. In classical music publishing you don’t get supernovas – and this was a supernova.”

The work has retained its place in popular culture. A recent recording featured Beth Gibbons from the band Portishead, and its strains have graced film soundtracks from The Tree of Life to Suicide Squad. Now it’s about to become an opera of sorts – English National Opera has just announced a staging of the symphony, directed and designed by Isabella Bywater, will be at the Coliseum in London in April 2023.

Górecki’s symphony was not completely alone aesthetically. Several other contemporary composers, including Arvo Pärt and John Tavener, displayed a similarly spiritual bent (their music was sometimes known as “holy minimalism”), and minimalists such as Steve Reich had already disrupted the status quo. But only Górecki’s album sold in such numbers: a new classical mainstream did not emerge.

“For me the success of the Third Symphony was an isolated phenomenon,” says the Guardian’s chief classical critic, Andrew Clements. “It just caught on, almost like a novelty record.”

Kenyon puts it thus: “What first minimalism and then these pieces” – such as Pärt’s Passio and Tavener’s The Protecting Veil – “did was to show that there were other directions in classical music: there wasn’t going to be a mainstream any more.”

Although appreciative of his success, Górecki had the mixed feelings typical of a one-hit wonder – yet he understood the impact of his hit. In a 1993 Time magazine interview, he reflected: “Perhaps people, especially young people, find something they need in this piece of music, something they are seeking.”

Appearing on National Public Radio in the US in 1995, he read from a letter from a 14-year-old Swedish girl who suffered serious burns and lost her mother in a fire. She cherished her Górecki tapes. “I live only because you write such music,” she wrote.

As for Hurwitz, his passion still evident after 30 years. “In terms of its text and its hyper-emotional language, it could have been written today, about what is happening to the nextdoor neighbour of Górecki’s Poland,” he says. “What moment is there more need for sorrowful songs than right now?’