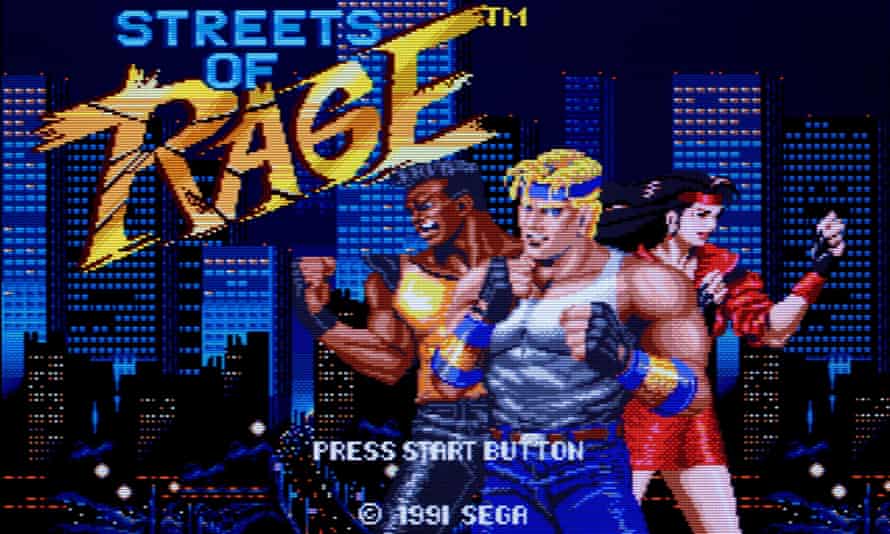

Sega, it seems, is having a moment. The veteran publisher’s movie sequel Sonic the Hedgehog 2 has become a huge box office success, hitting $300m in revenue, despite lukewarm reviews. It was also revealed that a film version of classic brawler Streets of Rage is in development, scripted by John Wick creator Derek Kolstad; some are postulating that this could be the beginning of a Sega Cinematic Universe. And last week, sources within the company revealed to Bloomberg that reboots of classic early 2000s titles Crazy Taxi and Jet Set Radio are in development, part of a new Super Games initiative to build Fortnite-like communities around its titles.

Why so much Sega? Why now? Sonic the Hedgehog 2 has perhaps arrived at a good time with families venturing out to cinemas once again, desperate for something lighthearted that everyone can enjoy – and not having much choice when they reach the multiplex. And whatever you think about the finer points of the movie, it’s fast and fun, with an amusing performance from Idris Elba as Knuckles and Jim Carrey back to his hammy, gurning best. It captures the feel of those original Mega Drive games, with their madcap, screwball energy and bright, blue-sky optimism.

More importantly, unlike Nintendo games, which have mostly been aimed at insulated family groups, Sega titles are for communities. Most of the company’s greatest games were developed for the arcades of the 80s and 90s, when they were jammed with teenagers, playing, watching and socialising, with the arcade cabinets as the central focus. When veteran designer Yu Suzuki began to build the classic “taiken” or “body sensation” games of the late 80s – such as OutRun, Space Harrier and Afterburner – his aim was to attract non-players into the arcades. He wanted people to come and watch, to enjoy the games as a performance, something cool to do on a Friday night with friends, or with a date.

Later, in the 90s, younger Sega producers such as Tetsuya Mizuguchi, Kenji Kanno and Kazuki Hosokawa brought in a wealth of modern pop, art and music influences, so that their games felt like extensions of the Tokyo street cultures they understood. The graffiti-and-rollerskates action game Jet Set Radio combined fashion,hip-hop and skating into an experience that felt like being part of a gang. At a time in which we’re all trying to reconstruct friendship groups and social activities, a reboot seems like a really obvious idea.

Meanwhile, Crazy Taxi harked back to Suzuki’s philosophy of intuitive and immersive entertainment for all. Players drive around a sunny city collecting and delivering passengers in their cab, and while the mechanics of the game are deep, Kanno ensured the game was entertaining, even if you were terrible at it. The music, zany characters and bustling streets all created a place that was fun to explore – and the timer was more generous than most coin-ops of the era, giving players longer than the standard three minutes for their 100 yen. This idea of games as something accessible, chaotic and performative is a Sega trait.

True, Sega is now more of a publisher than a developer, and apart from the brilliant Yakuza series it hasn’t really created many era-defining hits since the early 2000s. But nostalgia is a big part of the appeal of the movie, and fuels the excitement around Crazy Taxi, Jet Set Radio and the forthcoming Sonic Origins, which packages up the hedgehog’s early adventures.

These Sega games tap into our seemingly endless reverence for a sort of glamorised simulacrum of the 80s and 90s, all blue skies and blazing sun and euphoric electronic music; they call to mind the era of mindless action movies, Saturday morning cartoons, LA rock bands in lipstick and big hair, Ferrari Testarossas, the beaches of Malibu and alleyways of New York. Sega is having a moment because we are desperate once again for the joy it provided, those beautifully pixellated skylines, shared in packed arcades, surrounded by other players, no cares in the world.