Even by the HFPA’s eccentric standards, Todd Haynes’ May December is a wild card in the Best Musical or Comedy category. But it does feature elements of both, in a deceptively dark story that harks back to the days of Hollywood’s self-imposed censorship code, when ingenious directors found sensitive and intelligent ways to address taboo subjects in mainstream movies. Here, the inspiration is the real-life case of Mary Kay Letourneau, a 35-year-old married teacher who, in 1997, seduced a pupil and was sentenced to prison for it, twice. A year after her release in 2004, claiming their love was “eternal and endless”, Letourneau married the boy, then 21. That wedding, and their subsequent life together, was covered, flatteringly, by the media. May December is not their story, but it does address two key points. What was she thinking. And how did the media become so complicit?

In May December, Natalie Portman plays Elizabeth Berry, a classy, well-known TV actress who has come to Savannah, Georgia, as research for her starring role in a biopic of Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore). At first glance, Gracie is just another middle-aged mom, sending her kids off to college, and the fact that her husband Joe (Charles Melton) is quite a bit younger doesn’t really seem so strange at first, given that he’s a handsome, solid and unassumingly capable presence. But after they meet at Gracie’s barbecue, the film that follows is an unravelling of all our preconceptions, in a story that seems — as the main players would want us (and themselves) to believe — to have turned out fine in the end.

We asked both actresses about their roles. Here’s what Julianne Moore had to say…

DEADLINE: How did you get involved with May December?

JULIANNE MOORE: Well, this is my fifth collaboration with Todd. We’ve been working together for 30 years, which is kind of crazy. Jessica Elbaum, who is one of our producers from Gloria Sanchez Productions, sent the script to Natalie, and Natalie sent it to Todd to direct. And Todd, because we had this very long, really wonderful artistic collaboration, slipped it to me. He emailed it to me and said, “Hey, I want you to look at this: Natalie Portman sent me this script, and there’s a really great part for you.” And I was like, “Wait, are you going to be directing this?” He was like, “Yeah, I think so.”

I read it, and I flipped out. It was astonishing, and so complicated, and emotional, and strange, and demanding, and also incredibly unusual in that it had these two female characters in this, like a Face/Off sort of relationship. So often when you find two female characters opposite each other, either it’s a love story or it’s a familial relationship. And this was unusual, because here are these two very strong women who are in a struggle for narrative dominance. It was so, so unusual. Anyway, I said, “Yes, absolutely,” right away.

From left: Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman.

Francois Duhamel/Netflix

DEADLINE: It’s inspired by the real-life story of Mary Kay Letourneau. How much did you know about that?

MOORE: Samy Burch, who was our screenwriter, grew up in the ’90s, which was kind of the height of tabloid culture. Those were the days when we still had magazines on stands, and all these images were splashed across them. There was Mary Kay Letourneau, Monica Lewinsky, O.J. Simpson, and all of these kinds of tragic and somewhat lascivious stories were everywhere. So, yes, I was aware of it. In the United States, it was impossible, if you were around at that time, to not hear these stories. But I wasn’t highly educated.

DEADLINE: Did you do any research into the story at all?

MOORE: I did a little bit, but Todd was very clear, and Samy as well, that the screenplay was our document. That was where we based most of our work. It was interesting. There’s certainly a lot of documentation. There are television interviews, and there were magazine articles, and books, and I think we used some of them as references, but we were always very, very aware that we were telling the story that Samy had written.

It was challenging. I mean, for me, I think one of the things that was so compelling is her insistence on her personal narrative. I think that, psychologically, when someone has transgressed, but insists on presenting their narrative as not a transgression, as something utterly ordinary, I think people have a feeling of danger around them. Something feels uncomfortable, like being gaslit. I was so interested in it, and so compelled by it, and even frightened by it. It’s really scary when somebody demands — when somebody insists on — a narrative that’s patently untrue.

DEADLINE: You chose to play her in an eternal present: Gracie always seems to be in the moment…

MOORE: Oh God, absolutely. I think it’s too painful for her to examine [her past]. These are two women who are incredibly self-regarding, but they don’t really look at themselves and their actions. But I do think that, with Gracie, there’s such a huge, huge difference between the narrative that she’s promoting, and the reality of what happened. There’s this vast space in between those two things. Because you see, in her private moments, her incredible emotional volatility. She falls apart all the time, and she’s sobbing all the time. There’s a tremendous amount of shame, remorse, and regret in there, but she can’t face it. She can’t look at it. So, she goes forward by staying in the present and staying, I think, in her fantasy.

DEADLINE: Seeing the film a second time reveals more about Gracie. Like the fact that she falls apart when a cake order is canceled. Even though the customer is clearly in the middle of a family crisis, Gracie makes it all about herself.

MOORE: She’s tremendously selfish. She’s tremendously self-centered. She’s not crying because the cake has been canceled, she’s crying because she’s so ashamed. She has a lack of awareness about herself, or lack of self-examination. I do think she’s incredibly, incredibly self-centered. Also, she ropes Joe into that, and she always has. You realize this is somebody who’s elevated a child to the status of a man, in order to have this romance that’s going to rescue her from her life. So, like I said, that’s something that’s kind of shocking.

DEADLINE: You didn’t have any rehearsal time, did you?

MOORE: None, yeah.

DEADLINE: So how did you prepare to play a character that’s being studied — and copied, basically — by Natalie’s character?

MOORE: Well, that was something that Todd and I spoke about explicitly, because we had very limited time, and Natalie was going to have to become me, or learn my mannerisms immediately. Therefore, I needed to really think about who Gracie was, be prepared with who she was, and then offer up things that were absolutely concrete for her to imitate. So, as I was doing my research on her, I realized that Gracie was someone who was so incredibly inculcated in gender, it’s as if she’s swallowed gender whole. I thought about her having this kind of hyper-femininity, so, physically, I came up with the way that she moved, and held herself, and her presentation was super, super feminine.

And then there’s her insistence on her naivety. I started thinking: what would be an outward manifestation of that? I hit on this idea of a lisp, which is a childlike characteristic, and often happens when kids don’t have enough musculature in their mouth. I called Todd, and I said, “I’m thinking about this. I think it’s something very concrete then that I could have, that Natalie could imitate.” That’s how it came about. It was really an interesting process, because I’ve never done that before. It was exciting to work on it with Todd, and then offer it to Natalie. She didn’t hear the lisp until we did the first scene.

DEADLINE: Seriously?

MOORE: Yeah. Because we didn’t discuss it. So, we did the first scene together, when she comes into the barbecue, that was the first time she heard it. And then when we were doing the dress shop scene, I have my arms crossed, I’m making these hyper-feminine gestures, and I can see, out of the corner of my eye, that Natalie’s doing the same. Of course, Gracie, who is so desperate for approbation from Elizabeth, is seeing herself reflected back in a way that she wants to be seen, and she feels pleased by it too. So, it’s this wonderful kind of symbiotic relationship that Natalie and I started having right away.

DEADLINE: Gracie and Joe live very well, but they don’t seem to have any income. Why is that?

MOORE: Well, there’s a line that you might’ve missed, because it’s only mentioned once. When we’re in the dress shop, and I’m showing Natalie the photos of the wedding, I talk about selling our story — selling our wedding story — and that’s how we got the house. If you hear it, it’s, like, one little line. But it’s funny, because my father asked the same question. He saw the movie, and he was like, “I don’t understand where she got that house.” I said, “She sold her story to the tabloids.” So, you realize that this is something that Gracie’s been doing for a while. I think you’re the first journalist to ask this question, actually, so I’m pleased, because it’s something that I think is implicit in the story, but it’s only mentioned once. Not a lot of people have picked up on it. They don’t have significant income. She’s a home baker, and he’s working as X-ray tech, but they have this big house, and they have these children. So, it’s like, how do they do it? And you realize they’ve sold these stories to the tabloids.

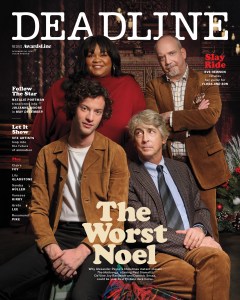

From left: Charles Melton, Julianne Moore, Natalie Portman and Todd Haynes.

Getty Images

DEADLINE: The camera is literally a mirror throughout the movie. Could you talk about how that idea came up, and how it worked for you?

MOORE: Well, Todd is a master of construction, he really is. He has a formidable intellect, and a real knowledge of cinema; how you shape a scene, how you tell a story. And he created this wonderful distance in the way that he framed us, in these wide masters, where we kind of step in and out of the shot. And then all of these images were reflected back to one another. As I said before, Natalie and I played these characters who are incredibly self-regarding, so the idea is that we can look into a mirror and see ourselves but not examine ourselves. And so, what does it mean to see yourself and not look? How does it change your own performative identity when somebody else is looking at you, as you’re looking at yourself? Is this really who you are? Are you performing identity because you’re being seen? And I think both of these characters are characters that are performing all the time.

DEADLINE: The makeup scene is especially important in that regard.

MOORE: That’s my favorite scene. That’s absolutely my favorite scene. It’s remarkable because it’s a moment of their truest intimacy. They’re in this one shot together, and it’s in one take, doing something that is performatively female: putting on makeup. I think that Gracie is really saying to Elizabeth, at this point, “I want to put my face on you. I want you to feel what it is to be me.” And so, the two of them face each other, and then have this incredibly intimate conversation about their mothers. It’s so revealing of who they are, what their background was. Particularly Gracie. When Elizabeth says, “What was your mother like?” Gracie says, “She was beautiful.” And that’s it.

Technically, there was a lot of concern about getting Natalie’s hair out of her face, and they couldn’t tie the wig back, because it didn’t look great. I said, “I’ll do it. Let me just push her hair away from her face.” I love Natalie, and we got very close, very quickly, and really enjoyed being with each other. I think our closeness was helpful, because it just makes you want to do more. And, really, that moment of touching her, is incredibly intimate, and very seductive. Like I said, these are women who are in a battle for narrative control, and one of their methods of dominance is seduction. So, there is this seductive quality to what Gracie is doing to Elizabeth at that moment as well.

It was challenging, because I needed to get my makeup on Natalie in real time, so that when we turned into the mirror to look at each other, the level of saturation of makeup, color-wise, would be the same as mine. Honestly, that was my biggest challenge.

DEADLINE: When they all go for dinner before the graduation, is that the first time Natalie’s character starts to lisp and speak with Gracie’s voice?

MOORE: You’re probably right. I think that’s when she’s fully inhabiting Gracie. It was wonderful for me, certainly as Natalie’s acting partner and even as Gracie. Natalie’s sitting right next to me, and we’re kind of twinning in our outfits, in our attitudes, and even vocally. And it feels oddly pleasant to Gracie, because she’s feeling seen. She’s feeling corroborated.

DEADLINE: Gracie is always giving her children a hard time about their weight and their body shapes. Would you consider her to be a bad mother?

MOORE: I don’t think I would categorize it that way. I think she’s somebody who’s really very, very self-involved. Incredibly self-involved. And I think she has expectations for her children that are highly genderized. She talks to her young son about getting big and strong before he goes to college. Putting on muscles and being a man. She talks to her daughters about weight, saying. “This is something that you have to be concerned about.” Or she veils it, I think, with one of the comments about being a modern woman, “I was never that,” she says. “You’re so lucky that you are.”

And that wonderful line, “You try going through life without a scale, see how that goes.” [Laughs] I mean, it’s a very funny line, but it’s also horrific. But I think what Samy’s done so beautifully with that line is that it’s also a condemnation of gender culture. At the same time that Gracie is being maybe not the most helpful parent, she’s also saying, “This is the world that I grew up in. This is the world that has shaped me, and this is kind of oppression that I’m living with.” Not to let her off the hook at all, I just think it’s compelling.

Todd has always been interested in identity, and culture, and how we’re shaped by it, and who we are, in terms of how we live, and when we live. Our identity is not shaped out of nowhere. It’s shaped by the world, the culture, and the time that we live in.

DEADLINE: There’s also lot of that going on in Charles Melton’s performance as Joe.

MOORE: Oh, he’s wonderful. I mean, he’s really, really terrific. I was there with him when he auditioned, and I was like, “This is the guy. I can’t see anybody else doing this.” He has this amazing availability as an actor, someone who can just really sit there and receive. And so receptive to all of Gracie’s incredible volatility. He’s just like, “OK.” And you felt kind of the weight of that history, that this is somebody who’s been on the receiving end of this kind of barrage of emotions for a very long time. But he was also able to communicate, as someone in a state of arrested development, a kind of an opacity, like, not quite understanding what had happened to him. And I think his gradual realization that maybe he has been gaslit, that maybe this wasn’t the big romance that Gracie claims that it was, is really beautiful to watch. And also, he’s the loveliest person. My God, he’s a great person. He works so hard. He’s a real team player. I loved being with him. It’s wonderful to see a talent like him.

From left: Portman, Moore and director Todd Haynes on set.

Francois Duhamel/Netflix

DEADLINE: Todd used a lot of music on set, notably Michel Legrand’s music for Joseph’s Losey’s 1971 film The Go-Between. How was that for you?

MOORE: He actually emailed me about it really early on, long before we started working on May December. He just said, “Julie, I want you to listen to this score from The Go-Between, because this is an idea that I have for the film.” What happened so wonderfully in this Joseph Losey film is that you see all these relationships, these people behaving the way they do, and then this striking score pops in as a book end. It indicates to the audience, like, “Oh, you think you’ve been watching something that’s fairly normal, but I’m going to tell you, as a director: ‘No, there’s something else happening here.’” He was like, “I’m really interested in using music in this way.” And so, when we were on set, doing these scenes, he played it for us, so we would have an indication of how he was going to shape the film.

It was just wonderful. I mean, he’s a director who shares his inspirations and his process with his actors all the time. It’s a collective, a film experience, so we’re all in that process with him. And then, of course, later on, when he was thinking about scoring, he’d become very, very attached to the Michel Legrand score. So much had been created with that in mind, he and his composer ended up reinterpreting that score and using it in the film.

DEADLINE: Did he give you visual references as well?

MOORE: Yes. He always does that. Like I said, this is my fifth collaboration with Todd. He’s amazingly generous with his resources, and he’s incredible at communicating tone. Certainly, on the movies that he’s written himself, there’s so much that’s evident in his screenplays. And then when he offers you these cinematic references and influences you with the music. It’s a wonderful way to enter into a creative process with a director.

DEADLINE: Was there anything that was particularly useful for you?

MOORE: I’d say Persona by Ingmar Bergman. I think that’s the most definitive. This idea that we were going to watch these people relating in these loose frames, and then also the intensity — the idea of two women bearing down on each other’s identity and absorbing it.

Read the digital edition of Deadline’s Oscar Preview issue here.

DEADLINE: To go back to Joe, the film reflects his awakening from a very disturbing situation, and, because the film doesn’t judge these characters, the enormity of that creeps up on us. How do you feel about that, and what reactions have you had from audiences?

MOORE: You’re right, it doesn’t judge the characters, it sort of presents them. We enter into this movie with Elizabeth, and we believe that she’s going to be a reliable narrator, and then, of course, she turns out not to be. So, it makes you question the nature of storytelling and how we present our stories to the world. What do we believe? What actually is the truth? Are we ever going to get to the truth of anything, or of any human being? This idea of a shared truth — does it even exist if people are always telling their own stories?

I love the ending of the movie, where you see Natalie’s character attempting to recreate this story in the most banal way. After all of this intimate, emotional exploration, you see her on a set with a boy and snake, saying, “I want to do it again. I want to do it again. It’s getting more real.” Again, what is real? What do we know? What is truth? Is everything performed?

People keep asking me, “What happens next?” [Laughs] We’re all so soothed, sometimes, by films, books, and storytelling, where everything is sewn up. But, in fact, there very rarely is that feeling in life. We don’t know. We live in a state of suspension. And this movie sort of ends on an inhale, rather than an exhale. And, in that way, I think it promotes discussion about behavior, and identity, and culture, and narrative, and our desire to tell stories.

DEADLINE: Are you relieved that people see the humor in it?

MOORE: Oh God, yeah, of course. Life without humor is deadly, right?