These artists got a flaming hot deal when they paid just $175,000 for a rundown firehouse located in one of Brooklyn’s trendiest neighborhoods. Better still, their unusual digs — worth millions today — became a crashpad for some of the world’s biggest recording artists and their crews — from Blondie and Pink Floyd to Johnny Rotten.

But it wasn’t such an obvious buy back in 1985.

The owners, married-couple Walter Kenul, a musician, and Janet Rutkowski, a sculptor, were reluctantly flung into the housing market after flooding issues forced them to leave their Long Island City loft.

They hoped their next home would serve as a nexus for their creative comrades and maybe that’s why they were drawn to a diamond in rough: The former headquarters of Fire Department Engine Company 38 at 176 Norman Ave. in Greenpoint.

The 6,000-square-foot, 1880s-era station was shut down in 1976, as NYC teetered on bankruptcy. In the years since, the once stately structure had fallen into disrepair.

Now, Kenul and Rutkowski — who are in their 60s — have given The Post an exclusive look inside their renovated abode.

While Kenul tells The Post he did his best to “maintain the character of the building,” the space today has a modern, minimalist look. The four-bedroom, two-bathroom spread opens into a spacious but homey dining room, where wooden steps lead up to an airy kitchen and landscaped lower roof deck. Those cozy quarters give way to white-walled opulence on the upper level, where the ceilings over the sprawling living room and its fireplace soar to 12 feet. The room is decorated with original abstract art, traditional totems and steel sculptures, much of it Rutkowski’s own works.

The primary bedroom for years was the now-empty, skylit loft over a guest room on the floor’s southern side, but the intense summer heat eventually pushed Kenul to wall off a northern corner for a more temperate sleeping area. A bathroom adjacent to the loft features a dark-tiled Jacuzzi tub beneath a stained glass window and chandelier, and a tight, spiral staircase leads up to a quaint roof-level room where firemen once hung their hoses to dry.

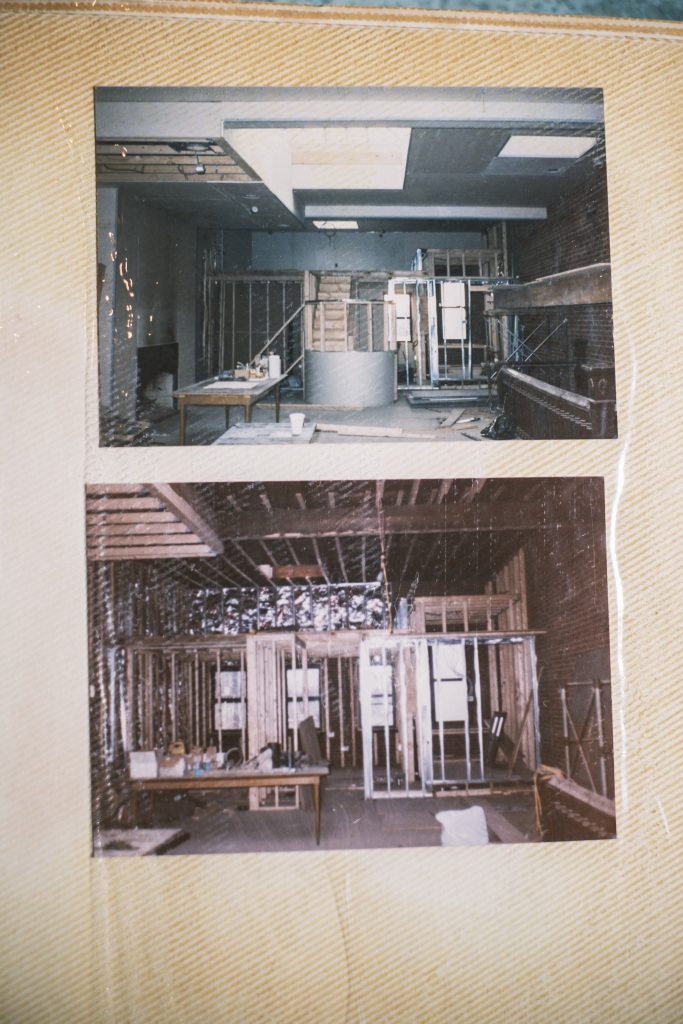

But DIYing one of NYC’s coolest apartments — legally, with city permits — was hard earned.

“The local kids had broken in and done all kinds of damage,” Kenul recalled of the building’s state when he bought it. The firemen’s pole had been stolen — “probably for the value of the brass, and went for heroin or crack” — and the brick facade was hidden behind plywood, the walls covered in cement.

The water and electricity were shut down. Worse still, there wasn’t a certificate of occupancy, meaning the pair couldn’t get a mortgage (that $175,000 1985 asking price translates to some $467,500 today, adjusting for inflation), forcing them to borrow cash from family and friends.

“[Robbers] broke the skylight, so water was coming in for five years and had deteriorated the beams,” said Kenul, who immigrated to NYC from the former Yugoslavia when he was 8. “I had no idea what I was getting into.”

But help began pouring in from handy relatives, fellow artists and even a stranger, named Richard Humann, who lived a few blocks away. Together, the scrappy crew heaved 30 dump truck-sized containers’-worth of rubble down the holes where the old fire pole once stood. And even while construction was ongoing, they began throwing parties.

“We invited some neighborhood artists and had an open studio art show on the ground floor — a guerilla art show in the middle of this construction site,” said Rutkowski, whose primarily metal welding work is displayed throughout the house in the form of steel sculptures, a coffee table, parapet and “Oracle Chair.”

Finally, after two years, Kenul and Rutkowski moved into the third story and Humann — a neo-conceptual artist whose heady creations include an ongoing augmented reality series that was most recently displayed over the High Line — started working and living out of the second. They had rebuilt the structure from head to toe, save a brick wall and the stairs’ oak handrails. Outside, they’d preserved the facade, including the Brooklyn Fire Department “BFD” engraving, and had a set of custom iron gates installed in front of the building’s entrance.

“I tried to salvage whatever I could, but there wasn’t much I could save,” said Kenul, adding that he did manage to repurpose some of the “huge slabs of slate” from the old shower stalls into a dining room table.

On the ground floor, they lofted the 2,500-square-foot space previously home to the firehouse’s horse stalls, and rented it to a music business.

“Our first tenants downstairs, they were our neighbors in Long Island City and had just started a sound company,” said Kenul. “I was flat broke thinking, ‘Who am I gonna borrow from?’ when the road manager of Dire Straits came here and asked if we’d mind if they stored their equipment for a few months.”

He offered $3,000 for the favor. “It was a great beginning,” said Kenul.

The company — originally called Shadow Fax, then Firehouse Productions — became wildly successful, and soon members and representatives of Tears for Fears, Blondie, Pink Floyd, the Talking Heads and other groups began hanging out at the building.

“Any given day, I could leave my loft, walk downstairs and have a drink with Johnny Rotten or Robert Smith from the Cure,” said Humann, who is also in his 60s.

They put a single bed and fixtures in the building’s former hose tower and it quickly became a drunk tank and crash pad for visiting artists, musicians and any friends who “needed a place to stay for a week or two,” which once included Peter Gabriel’s daughter, said Kenul. The little room, with its spare furnishings and two windows, is “like a treehouse” he described.

Then, in 1990, Humann became enamored with the singer in Kenul’s band. The next year, she moved in, too.

“When I first walked in, I was completely awestruck. I had never seen anything like it,” said Susan Darmiento of moving into the firehouse at age 29.

She worked for the music company downstairs until they moved out in the mid-90s, (today they work with the Rolling Stones and the Lumineers, among other groups, and there’s a video production business in their old space) but the address has quietly remained an artist mecca.

“The whole building is full of art and creativity, which makes it this amazing oasis,” said Humann. “I don’t think there’s ever been a time this place didn’t have a crowd somewhere in the building. It’s like an extension of what my college life was like — I’ve been living my college dorm life for the past 40 years.”

Today, the residents are in a roots rock band called American Nomads, which has weekly practices in the building.

“It’s always been a gathering place for us, friends, artists, musicians — I think building this is the biggest art piece me and Walter ever did,” said Rutkowski who, with Kenul, raised their now 33-year-old son in the building.

Once, the grandson of a firefighter who had worked in the building stopped by to take photos. Kenul brought him inside and gave him five of the company’s old daily logs that he found on the property.

“He was so thankful,” said Kenul. “I have a million stories — the building has such great energy.”