By the early 2000s, Sega was in free fall. Once the king of the arcade and home console industry, the company that brought us Sonic the Hedgehog, Virtua Fighter, and Golden Axe was losing millions. The Dreamcast — Sega’s final attempt at console glory — had launched with a bang but died with a whisper. Sony’s PlayStation 2 had steamrolled the market. Sega was bleeding out.

Bankruptcy seemed inevitable. Analysts predicted a corporate collapse. Employees feared for their futures. But then, something happened that no one could’ve imagined. Actually two things.

Sega’s chairman, Isao Okawa, reached into his own fortune and did something truly unbelievable. And then he dropped dead…

The Origins: From Hawaii to Tokyo

Sega’s roots are surprisingly American. The company began in 1940 as Service Games, founded in Honolulu by Raymond Lemaire and Richard Stewart. It focused on supplying jukeboxes and slot machines to U.S. military bases in Japan.

In the late 1950s, a former U.S. Air Force officer named David Rosen founded his own coin-op game company in Japan, Rosen Enterprises. In 1965, Rosen orchestrated a merger between his company and Service Games, forming SEGA — short for “Service Games.”

With Rosen at the helm, Sega expanded rapidly. Paramount Pictures bought the company, took it public, and by the late ’70s, Sega was riding high on the arcade boom. By 1982, it was generating over $214 million in annual revenue.

But then came the crash.

The Console Wars: Sega vs. Nintendo

After a few ownership reshuffles, including a major acquisition by Japanese tech firm CSK, Sega emerged as a global player. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, Sega of America went head-to-head with Nintendo in what would become gaming’s first true console war.

Sega’s Genesis (aka the Mega Drive) was a smash hit. Backed by edgy marketing — “Genesis does what Nintendon’t” — and a new mascot named Sonic, Sega grabbed 65% of the U.S. market at its peak. But that success wouldn’t last.

Glitches, Lawsuits, and the Sega Saturn

In the mid-1990s, Sega’s momentum started to slip. The Sega CD and 32X were commercial disappointments. Then came the Sega Saturn — powerful, but expensive, difficult to develop for, and lacking a killer game at launch. It couldn’t compete with Sony’s PlayStation or Nintendo’s upcoming N64.

To make things worse, Sega lost a landmark lawsuit. In Sega v. Accolade, the court ruled that companies could reverse-engineer software to make their games compatible with Sega consoles — weakening Sega’s monopoly on its hardware.

By the late ’90s, Sega was losing millions and running out of lifelines.

Dreamcast: A Last Shot at Greatness

Sega’s final gamble in the console wars was the Dreamcast — a sleek, forward-thinking machine that launched in Japan in 1998 and hit North American shelves on the now-iconic date September 9, 1999 (9/9/99). It was a revolutionary system, boasting built-in modem support for online play, a custom operating system, and a lineup of genre-defining titles like Jet Set Radio, Crazy Taxi, Shenmue, and Phantasy Star Online.

At first, the gamble paid off. The Dreamcast’s North American debut was the most successful console launch in history at the time, with over 500,000 units sold in just two weeks, generating $98 million in sales. Gamers were dazzled. Reviewers raved.

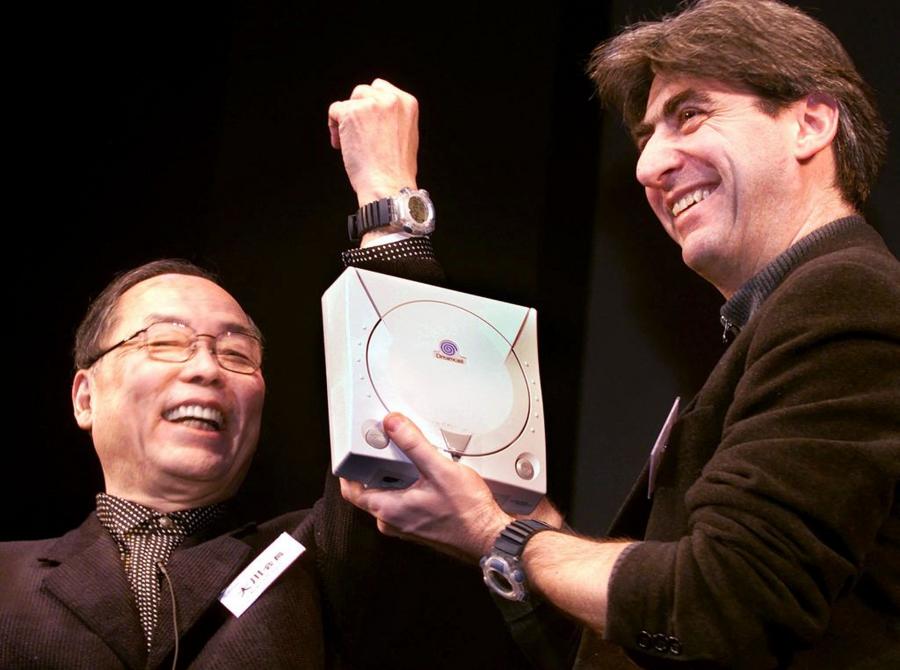

Below is a photo from February 4, 2000. On the left is Sega chairman Isao Okawa (who will become very important to our story in a moment. On the right is the President of the Swatch watch company. At the conference, they announced a new partnership, “Internet and Wearable,” a revolutionary new function that allowed the watch to synchronize with the Dreamcast… for some long-forgotten, probably pointless purpose. The idea was probably 15 years too early (the Apple Watch was announced in 2014):

(Photo by KAZUHIRO NOGI/AFP via Getty Images)

But the celebration didn’t last.

Just months later, Sony unveiled the PlayStation 2, complete with a DVD player, cutting-edge graphics, and an avalanche of third-party support. It crushed the Dreamcast in sales. Retailers began pulling shelf space. Developers shifted focus. Within a year, the Dreamcast’s fate was sealed.

In early 2001, Sega officially announced it was exiting the console business. The Dreamcast would be the company’s last home console.

Isao Okawa To The Rescue

As Sega’s financial losses mounted and the Dreamcast faded from the market, the company prepared for a radical shift — exiting the hardware business entirely to focus solely on software development. But the transition wasn’t smooth. Internal morale was crumbling. Investors were wary. Bankruptcy was very much on the table.

Then came a miracle — one that had been decades in the making.

Isao Okawa wasn’t just Sega’s chairman. He had been the quiet force behind the company’s survival for more than 15 years. Back in 1984, as Sega teetered on the edge after the North American video game crash, Okawa’s Tokyo-based tech firm CSK Corporation stepped in and acquired a controlling interest in the company. The exact purchase price was never publicly disclosed, but the deal was widely seen as a rescue acquisition. Sega’s U.S. division had just been sold off, and its Japanese operations were hanging by a thread. CSK’s backing brought stability — and with it, new leadership. Okawa became chairman of the newly restructured Sega Enterprises, Ltd., and the company was listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Over the next decade and a half, Okawa steered Sega through the highs of the Genesis era and the lows of the Saturn and Dreamcast. He wasn’t a typical executive — he was a philanthropist, a philosopher, and a believer in Sega’s creative spirit.

So in 2001, with the company once again on the brink of collapse, Okawa made an almost unfathomable decision: he gave Sega everything he had. He donated his entire personal stake in the company — including shares in Sega, CSK, Ascii, and NextCom. In total, his gift amounted to ¥85 billion, or $695.7 million at the time. Adjusted for inflation, that’s nearly $1.2 billion in 2025 dollars.

It wasn’t a loan. It wasn’t a bailout. It was a farewell gift.

Okawa asked for nothing in return.

Death and Rebirth

Shockingly, just days after his donation was announced, Isao Okawa dropped dead from heart failure at the age of 74.

Okawa’s sacrifice gave Sega a second life. The company fully exited the console business and leaned into software, mobile, and arcade systems. It released new hits like the Yakuza series (Ryu ga Gotoku), rebooted classics like Sonic, and developed popular franchises like Total War and Football Manager.

Sega also found huge success in Japan’s arcade and amusement space, creating satellite-based trading card games and massive multiplayer arcade systems.

In 2004, Sega merged with Sammy Corporation to form Sega Sammy Holdings, strengthening its financial base. Today, the company has a market cap of roughly $4 billion. All because one man believed Sega was worth saving — and gave everything to prove it.

Content shared from www.celebritynetworth.com.