“Ugh, P. Diddy is such a creep,” my 11-year-old daughter said one evening as we sat down to dinner as a family.

My heart sank. Federal authorities had just raided his house, and the items they found suggested activities I hoped went over my daughter’s head.

“Oh, what have you heard about that?” I asked, trying not to reveal more than she already knew — likely from social media or her friends.

Over the past five years of global crises, I’ve learned to approach her exposure to mature topics with curiosity, followed by an age-appropriate explanation and invitation to ask questions.

Today, her access to the news through a range of voices, credible or not, researched or hot takes, abounds across social media. In 2022, “Nearly half of U.S. teens say they are online ‘almost constantly,’ a significant jump from 24% in 2015,” the Pew Research Center reported. And yet, social media companies are reversing content moderation practices aimed at protecting teens and young adults, making it even more difficult to know what she is seeing.

Even if I institute social media limitations, I can’t control what her friends and classmates have access to, and shocking or salacious news gets around, particularly when celebrities are involved.

I’m grateful that whatever her father and I have done as parents, she’s still telling us the things she hears and asking questions.

When I was her age, I was infinitely more naive and had far less exposure to adult topics for my parents to explain — partly because my parents were reserved immigrants, but also because the what I consumed across TV, radio and print came from media organizations with guidelines around editorial integrity and content warnings.

In 1999, 64% of children said “they’d rather watch TV than engage in any other activity.” But, also in 1999, television, radio, music and print media all had practices related to editorial integrity and independence, and they used content warnings to support parents and kids.

In the ’90s, my knowledge of cases with adult content like O.J. Simpson or Monica Lewinsky was limited to broad strokes of scandal, guilt and ethics. Today, my daughter — younger than I was when those cases hit the news — is hearing explicit details about the trial of Sean “Diddy” Combs.

“I don’t know,” my daughter responded to my question at dinner, “just people at school talking about what they saw on TikTok, that he’s into kids, built tunnels in his mansion, which is giving creep. And people saying Beyoncé and Jay-Z were involved.”

“It’s awful,” I said to the dinner table.

“Are you really surprised?” my husband asked.

I guess I wasn’t. But a long forgotten memory resurfaced as I considered why this news was hitting me differently.

In the summer of 1999, I was 17 and studying abroad in Paris. I was a teen who did not experience “the teen years” of rebellion (my mother would corroborate this). I wanted to spare my parents from a third round of it, having watched them go through it with my two older brothers.

But that summer, I was away from home. And although I was dorming in a French convent with no boys allowed (not even a family member) and a 10 p.m. curfew, I found ways to push boundaries.

After a day of art studio time or sitting on banks of the Seine sketching Notre Dame’s flying buttresses, my classmates and I drank wine and smoked cigarettes in the convent’s courtyard. The nuns turned a blind eye to this transgression, maybe because they were French or maybe because if they allowed this, we were less likely to get in trouble outside their walls. We hadn’t broken curfew all summer, so maybe it worked.

Until Tuesday, July 20, 1999. One of the girls ran into the courtyard.

“Let’s go out to a fancy dinner tonight!” she cajoled. I did a mental calculation of how many francs I had left for the summer and tried to quickly work out if I’d have to skip any meals to afford this one.

“It will be our celebration dinner, to cap off the summer,” another girl said.

We found our way to Buddha Bar, a hot Asian-fusion restaurant that had opened a few years earlier and was known as a celebrity spot. We begged the hostess to seat us, a group of six.

“OK,” she acquiesced, “but you have to be out by 10:30.” This fact was repeated by our waitress again once we were seated.

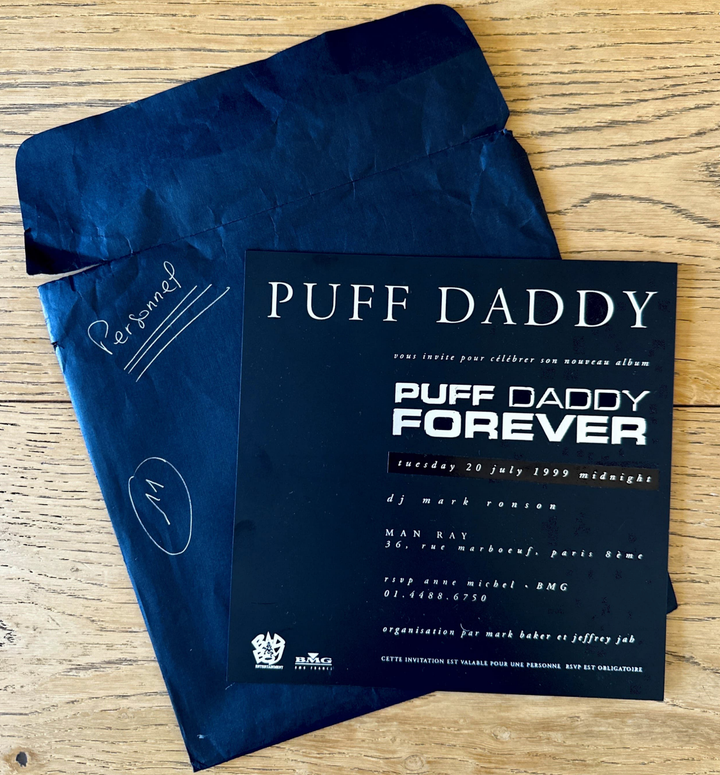

“It’s Puff Daddy,” one friend exclaimed on her way back from the bathroom. “There are posters everywhere.”

Photo Courtesy Of Ella Mei Yon Harris

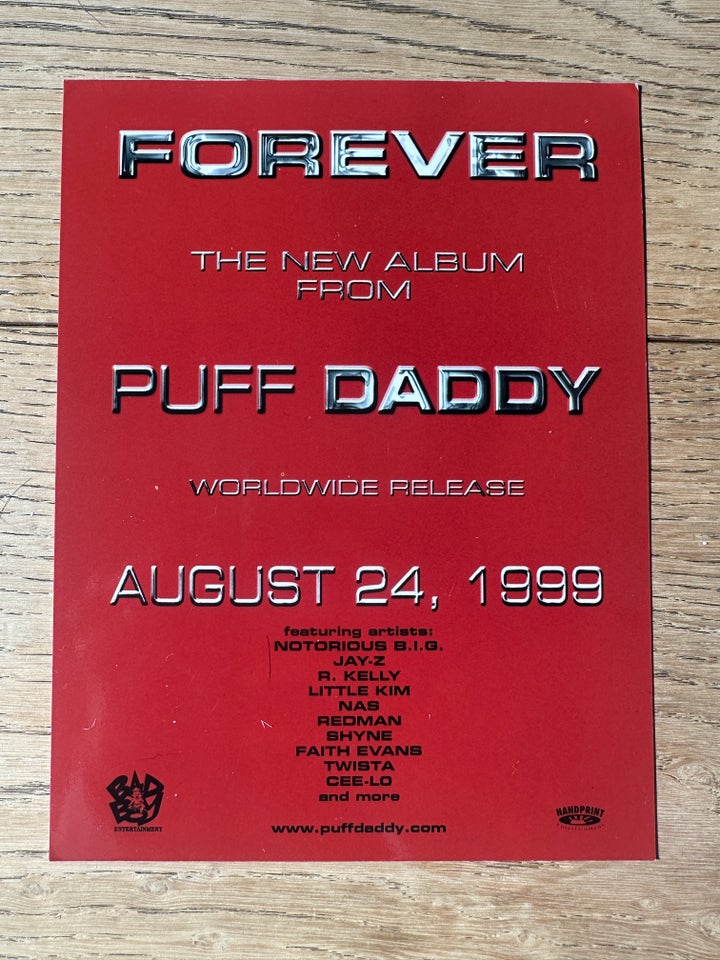

Puff Daddy, as he was called then, was fresh off the success of “No Way Out,” an album that mourned Biggie’s death, went multiplatinum and won a Grammy. He had launched Sean John, winning a CFDA award and was largely hailed a mogul on the rise. This was the European launch of his next album, “Forever,” during Paris Fashion Week.

“Let’s hide in the bathroom until the party starts,” one of the girls said.

I argued with the pit in my stomach, weighing this idea all dinner long. The pit in my stomach said, “What if they find us hiding? What if they kick us out? What if there’s serious security? What if we get arrested?”

“But what if none of that happens?” I reasoned back to myself.

So there I was, toes on one side of a toilet seat, heels hanging off, my friends on the other side. We held onto each other and to the sides of the stall until we heard the beats of a DJ we later learned was Mark Ronson.

We stepped out of the bathroom and into the elegant restaurant transformed into a dance club full of people. Lime-green cocktails. To sip or not to sip? I consulted the pit in my stomach.

We sipped. We danced with supermodels — Alek Wek, whom I’d admired as the first Black cover girl on Elle magazine, sauntered past me.

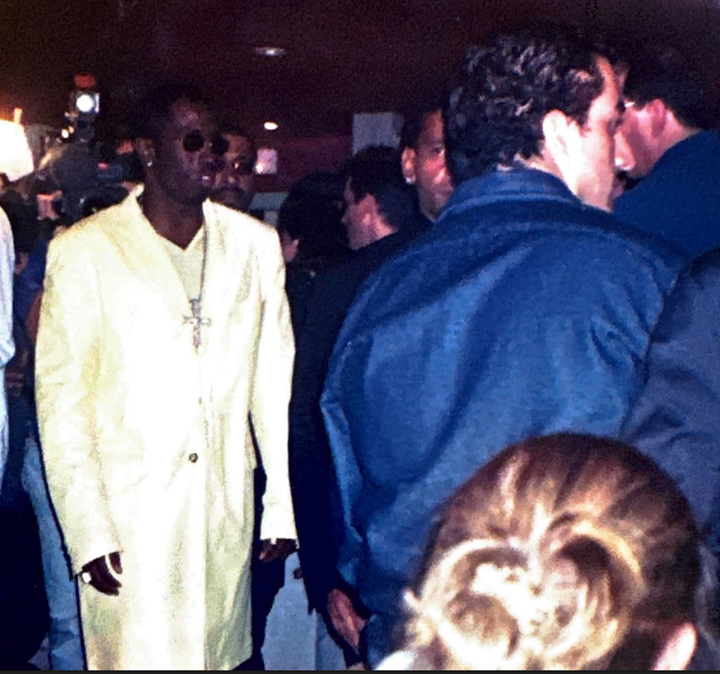

And then, Puff Daddy arrived somewhat quietly from a back corner. We watched from afar as he worked his way toward us. The spotlights reflected off his all-white, knee-length suit jacket and the diamond-encrusted white gold cross dangling in front of his chest. A man with a video camera on his shoulder and a fluffy mic on top trailed him.

My friend silently squealed at me with only her eyes as Puff Daddy brushed my shoulder. I laughed and rolled my eyes a little. It was cool, I thought, but he was just a guy. I knew nothing then of the unspoken societal power of celebrity and what it could condone, let alone enable.

The night devolved, but nothing like what has been described in the U.S. vs. Combs trial. At least not while I was there.

Photo Courtesy Of Ella Mei Yon Harris

“How have I known you for over 20 years and never heard this story?!” my husband said.

“You know me, I don’t really care about celebrities,” I said. “I haven’t thought about it in at least a decade.”

“I don’t believe you,” my husband joked.

“I probably have pictures and the invitations we stole on our way out,” I shot back, smirking.

“I want to see,” my other kids chimed in.

Weeks later, I did find them while clearing out my mother’s garage. At the bottom of a box full of pictures and travel mementos was a crumpled black square envelope containing two of the party invitations we swiped from the hostess desk, a flyer and a pile of photographs, including ones of Puff Daddy himself.

In the photograph of my friends and I around the dinner table, I look young and overly smiley. I can’t believe we lasted the whole night at that party without getting kicked out.

Photo Courtesy Of Ella Mei Yon Harris

I showed my daughter the evidence.

“Woah,” she said. “Mama, wait, did you do anything crazy?” I cringed.

“What? No. Definitely not.” I laughed nervously, praying she didn’t fully understand what had been reported. Who knows what happened at the “Forever” release party after I left, but 1999 was long before the 2007-2008 “freak-offs” that Cassie Ventura recently testified about.

“OK, good,” she said, relieved “But, wow, you went to a Diddy party.”

“I did,” I admitted, knowing that because this was highly uncharacteristic of me, it said something to her about the unspoken power of friends, celebrity, authority and hype.

“But,” I told her, “I’m really lucky nothing bad happened.”

“Ugh, yeah,” she said with a tinge of judgment. “Honestly, Mom, I would never.”

And although I know there’s a lot of time for her to make different decisions between now and when she’s 17, I’ve never been so happy to be judged by anyone.

Her careful judgment of me and my decision to ignore my gut.

Her ability to filter out all she’s hearing from social media and her friends.

Her verdict in the Combs trial, which has evolved from “creep” to “ew.”

It adds up to her learning to be her own editor of the content she consumes.

Photo Courtesy Of Ella Mei Yon Harris

More recently, driving to an after-school activity, she saw that I was listening to news from the trial when my phone connected to the car.

“Oh, the Diddy trial?” she said.

“Have you heard anything else about it?” I asked tentatively, because more graphic details had emerged.

“Nah,” she said. “I don’t pay attention to that.”

My innocence, like that of many girls my age, was defined by a lack of access — what we weren’t told, what we couldn’t Google, what no one dared explain.

My daughter’s innocence looks different. It’s not about ignorance; it’s about discernment. She consumes more than I ever did, but she also questions more. She sets boundaries I didn’t know I was allowed to have. In a media ecosystem without editors or gatekeepers, she is learning to be her own.

I used to think innocence was something we all lose. Now, I see it as something I can teach her to protect.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.

Content shared from www.huffpost.com.