Every so often, the estate of Nick Drake receives a rather unusual request: would the reclusive musician, who died in 1974, be available to play some festival dates? The requests are usually from abroad, says Cally Callomon, who manages the estate along with Drake’s sister Gabrielle, although he does recall a British culture show making a similar ask in the early 00s. Gabrielle once jokingly suggested sending one of her actor friends along to perform as Nick, although “I explained that this might get the booker fired,” laughs Callomon.

This anecdote tells you a lot about the enduring appeal of the British folk musician, who has been repeatedly discovered by new generations of music fans ever since his death from an overdose of antidepressant tablets almost 50 years ago. His music sounds so fresh that people assume he’s still alive.

This month saw the release of the first official biography, Nick Drake: The Life, to be followed in July by compilation album The Endless Coloured Ways, on which current artists reinterpret – sometimes quite radically – Drake’s back catalogue. Jenny Hollingworth from Let’s Eat Grandma is one of them, and the way she talks about connecting with Drake’s music for the first time will be familiar to many fans. “He writes in such an incredibly personal way, it’s hard not to feel like he’s directing it to an audience of one,” she says. Hollingworth first heard Pink Moon during lockdown, at an especially difficult time in her life – her boyfriend, the musician Billy Clayton, had died in 2019 of a rare form of bone cancer, aged 22. The final Drake album is a stark, stripped-back masterpiece, written and recorded on the precipice of mental deterioration. But rather than homing in on the record’s bleaker themes, Hollingworth instead saw it as a hopeful record. “Particularly because there’s so much about nature and the cycles of life, and about what nature can teach us about life and death,” she says. “I found it actually quite comforting.”

These are certainly timeless subjects – but how does Drake keep making a deep connection with each new generation when he was so commercially unsuccessful in his short lifetime? I vividly remember my own first encounter with his music: buying his second album Bryter Layter around the time I turned 16 and being almost physically overwhelmed by how deeply the songs connected with my then extremely sensitive self – it felt as if he was the only person who truly understood me back then; it also felt as if I was one of the only people who knew about him. It’s only now, after speaking to Callomon, that I realise that this wasn’t unintentional.

Rather than splash adverts around or force Drake’s back catalogue down the throats of the public, Cally and Gabrielle take a more subtle approach to managing Drake’s estate. The key, says Callomon, is to “say no to most things”. Advert soundtracks get turned down frequently. A biopic is out of the question (“everyone has their own idea of Nick and that would ruin it for them”), as are soundtrack opportunities for films that focus too explicitly on suicide or mental illness. They have released rarities but don’t want every last scrappy recording put out there. “As much as I love Jeff Buckley, post-death I’ve since counted 19 different variants on his one studio album. And I think every time that happens, you don’t double anything, you halve it,” reasons Callomon.

It would be easy to assume that there was no marketing behind Nick Drake at all, but as Callomon admits: “There is always a tactic.” In the 90s this was carefully placed reissues. In the 00s there was a Radio 2 documentary fronted by Brad Pitt and a carefully considered advert in the US for Volkswagen that used the song Pink Moon as its soundtrack. More recently there has been a coffee table book edited by his sister (Nick Drake: Remembered for a While) and cautious dabbles with social media. “We set up a Facebook page because that’s like a youth club,” says Callomon. “But just because some technology has been invented doesn’t necessarily mean it’s right for our audience.”

Eamonn Forde’s book Leaving the Building: The Lucrative Afterlife of Music Estates describes the myriad ways the Drake estate goes against conventional thinking. “If you look at the current drive to buy off huge catalogues [of songs] for tens of millions – people like Hipgnosis – they’re going to want to put all of those catalogues to work immediately and try to generate huge sums of money from the off,” Forde tells me. “But the Drake estate almost represents [Nick’s] own nature. He wanted to be famous, but he didn’t like the mechanisms of it. And I think they want him to be remembered, but for the promotion around him not to feel like promotion. They want it to feel as classy and as subtle as his own music.”

Until recently, the estate had long resisted an official biography – preferring to leave people to form their own personal image of Nick. Part of Drake’s appeal is the scarcity of information around him – a handful of photos, three albums with minimal outtakes, no known video footage. But this can lead to outlandish myths building around him that don’t get corrected without an official story. “We are never consciously trying to build up this tragic, romantic story as a way to sell the music,” says Callomon firmly. “One reason for doing the book has been to get away from the mystery of Nick Drake, the person.”

Nick Drake: The Life instead consists of an astonishing amount of what its author Richard Morton Jack calls “amateur detective work”. The result is the most factual and detailed picture of the singer’s 26 years on Earth we are ever likely to read, debunking many of the myths – that he was an addict, that he was gay or struggled to come to terms with his sexuality – on the grounds that, as Morton Jack puts it, “there was simply no evidence to suggest they were true”. Instead, the book details the journey of a happy child who grew up into a popular but increasingly distant adult, slowly losing touch with other people and then, tragically, his own talent. The final sections, which document Drake’s mental health problems without any romanticised garnish, are particularly harrowing.

“It’s just trying to describe the life rather than trying to plumb the depths of his soul,” says Morton Jack, “which I always think is a bit of a fool’s errand. I was never hoping to solve that or to approach him like a cryptic crossword clue. It was more about just trying to fill in all the extraneous stuff.”

Initially I was worried that such an abundance of factual information – along the way we learn Drake’s London landline number and the name of the bloke who circumcised him – might ruin my own version of Nick. But the detailed picture of Drake’s life actually allows you to understand and appreciate the music more – especially Pink Moon, which was written and recorded without his label Island even knowing, at the precise point Drake was losing touch with reality yet still retained his songwriting talent.

A year later and Drake’s mental health was so bad that he would be heard in his parents’ music room playing the same riff repeatedly for hours on end. Drake’s complex disorder may have been a type of schizophrenia – certainly it led to extremely unusual patterns of behaviour, such as his repeated attempts to drive to London in his final days, sometimes needing to be rescued by his father, sometimes not even getting out of the driveway. Those final passages are a grim read, but Morton Jack says he was determined to paint the reality of what life was like for the Drake family: “Nick fans, for all the right reasons, want him to have been happier and more likely to recover than he was. People want to believe that mistakes were made which could have made him survive and give us more music and bring him round again. But I wanted to show a sense of the complete hopelessness which his family felt. They tried everything.”

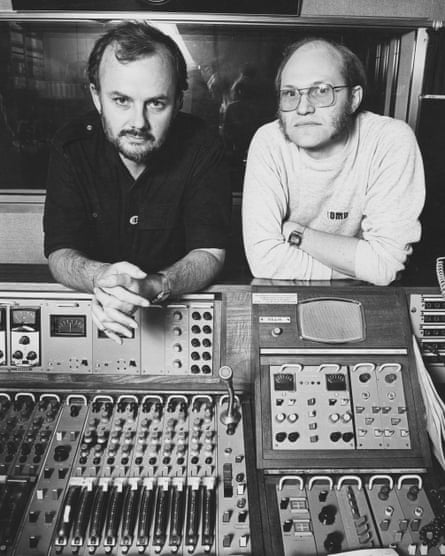

Like his fans, real life friends of Drake were often unswervingly loyal to him. As was Island (who never let his back catalogue go out of print) and his manager and producer Joe Boyd. Boyd had a grand vision for Drake’s music, and considered his songs to be future standards that would be constantly reinterpreted. This hasn’t come to pass – people can be overly reverent towards Drake’s music, or want to conquer his complex tunings as if they were simply a challenge to be mastered.

But that seems to be changing. Let’s Eat Grandma’s Hollingworth transforms From the Morning, the final song on Pink Moon, from a gentle finger-picked folk song into a cinematic, 80s-sounding synth anthem that somehow stays true to the heartfelt mood of the original, while coaxing out the song’s big-picture optimism. “I wanted to pull out that hopeful element,” she says. Elsewhere on the forthcoming compilation, Fontaines DC heartily amplify the rhythm of Cello Song and Self Esteem locates an uplifting mantra within Black Eyed Dog, formerly the starkest of howls into the abyss.

Similarly, in 2021 Demian Dorelli, a pianist from London, was bold enough to reimagine the entire Pink Moon album for piano. “I wasn’t singing and the challenge was to see if we could do that on piano alone, and not have the voice, which was a huge shock for a lot of Nick Drake fans,” he says. “But the feedback has been really good.”

Dorelli has a theory regarding why people are increasingly drawn to Drake’s music. “I see my daughters talking about mental health a lot, and there’s a lot of discussion around that on social media,” he says. “I think he taps into that and does it in a way that’s strangely uplifting … it gives you a bit of relief to know that somebody else is going through the same thing.”

Dorelli now lives in Cambridge just like Drake did for a while, and has occasionally performed his songs alongside Trevor Dann who wrote an earlier biography of Nick Drake in 2006 called Darker Than the Deepest Sea. Dann was an especially early Drake fan, buying the debut album Five Leaves Left when it was released and attending not just the same Cambridge college as Drake (Fitzwilliam) but requesting to lodge in his room, too.

“What people like about Nick is the fact that he is a troubled young man,” says Dann. “And there will always be troubled young men from Keats onwards. It’s a tradition of being kind of upset with the world. And he expresses a lot of that, I think, in his music. He’s not like Morrissey but they have something in common which is that they find some kind of satisfaction in expressing their misery, which speaks to younger people.”

Dann knows about the enduring appeal of Drake better than most: “Every quarter I get a little royalty statement for my book. It’s a matter of pennies now, but the fact is that it still sells all over the world. And that must be because in every town, all over the world, there’s always one or two Nick Drake fans, needing that kind of sustenance. And what he brings to them is that feeling of ‘it’s all right to be miserable.’”

There is no love lost between Dann and the estate: Callomon says Dann’s book is “more about Trevor than anything else” while Dann believes that the new biography is likely to be “Gabrielle’s version of the truth” rather than a truly independent piece of work. I’m not sure that’s the case. Morton Jack’s book never shies away from the grim realities of Drake’s descent, nor does it avoid criticisms of the singer’s somewhat privileged attitude. But it certainly paints a rosier picture than Dann’s book.

“The more I researched, the more I realised that he wasn’t very popular,” says Dann. “Many people who met him didn’t like him. They thought he was overconfident. And the word I think we’d use now is entitled. And you get a real sense of his disappointment at not being an instant pop star, being to do with, well, what have I done wrong? Come along, I’m an upper class boy. Everything’s meant to go well with me. My sister’s doing very well, acting, and I’ve got no money at all, and somebody must be to blame, and it obviously isn’t me.”

It’s clear how difficult it is for people to alight on any one impression of this elusive man. Even Drake’s closest friends all seem to have distinctly different images of him. And however much you might learn you’re still always left hankering for more pieces of the puzzle. I was astonished to find that, after absorbing all the fine details of Morton Jack’s book, I still viewed Drake largely as an enigma.

Is this what keeps subsequent generations enthralled? Quite possibly, but only because this enigmatic nature is so deeply intertwined with the music itself.

“It comes through in his lyrics, and it comes through in the music,” says Dorelli. “Even with the guitar, you can never quite work out what he’s doing. It becomes a story itself – one that you can’t get enough of.”