David Salle, photographed by Frenel Morris. All artwork images courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London.

David Salle’s assistant greets me at the door of his studio in the East Hamptons on a very late August afternoon. David will just be a moment. It’s about to rain. Light falls through the skylight and cools on the concrete floor, where steps strangely don’t echo.

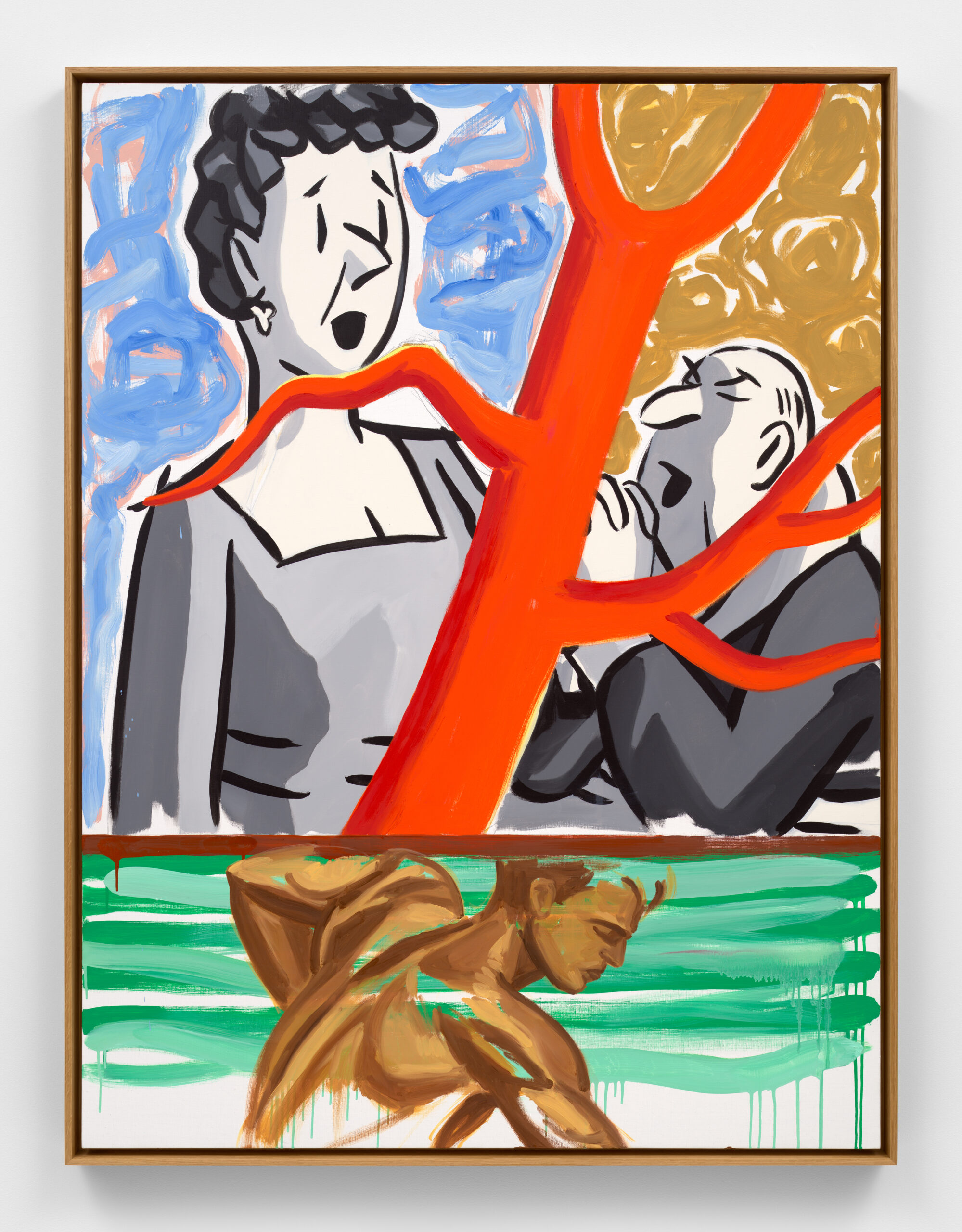

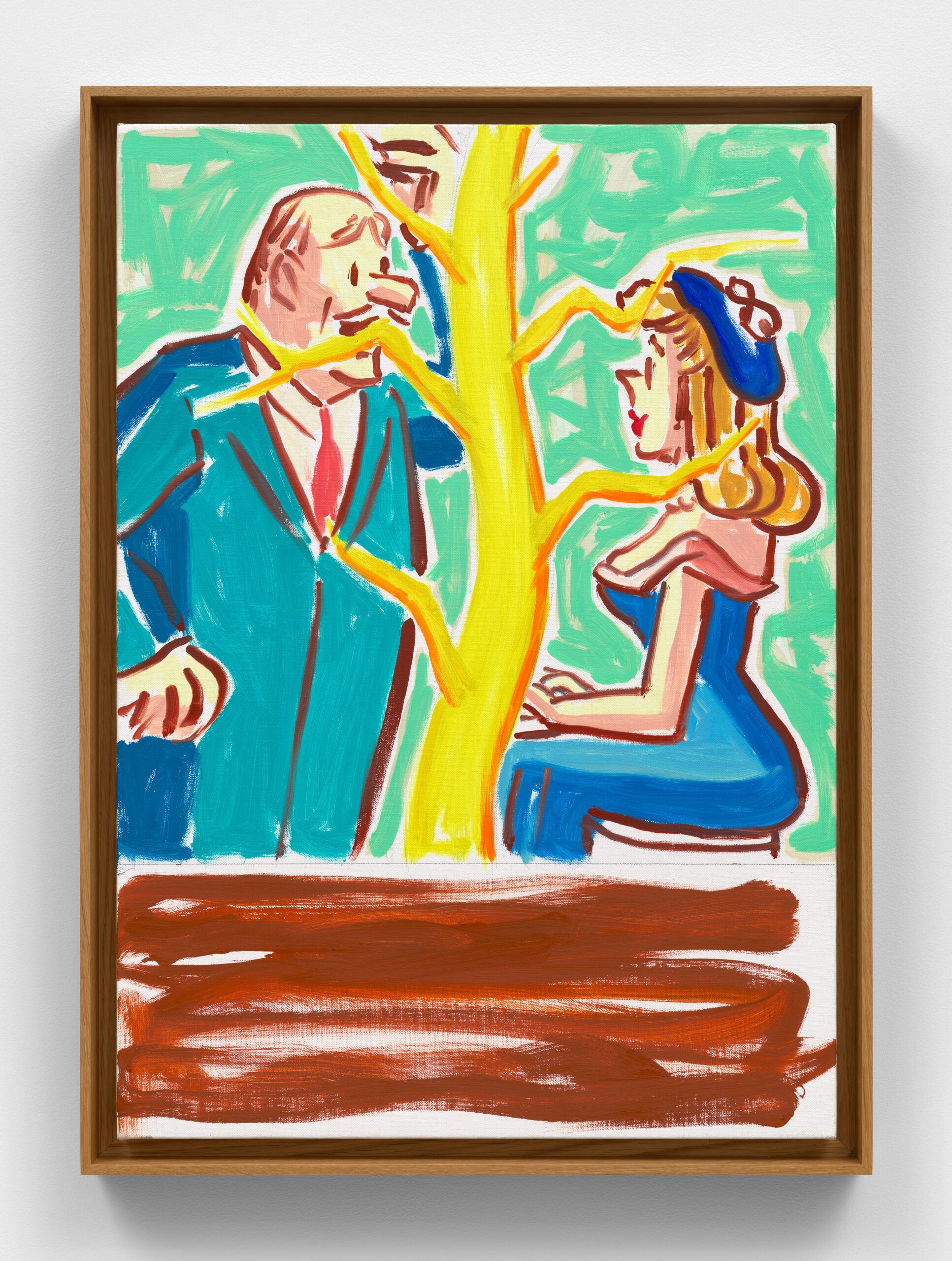

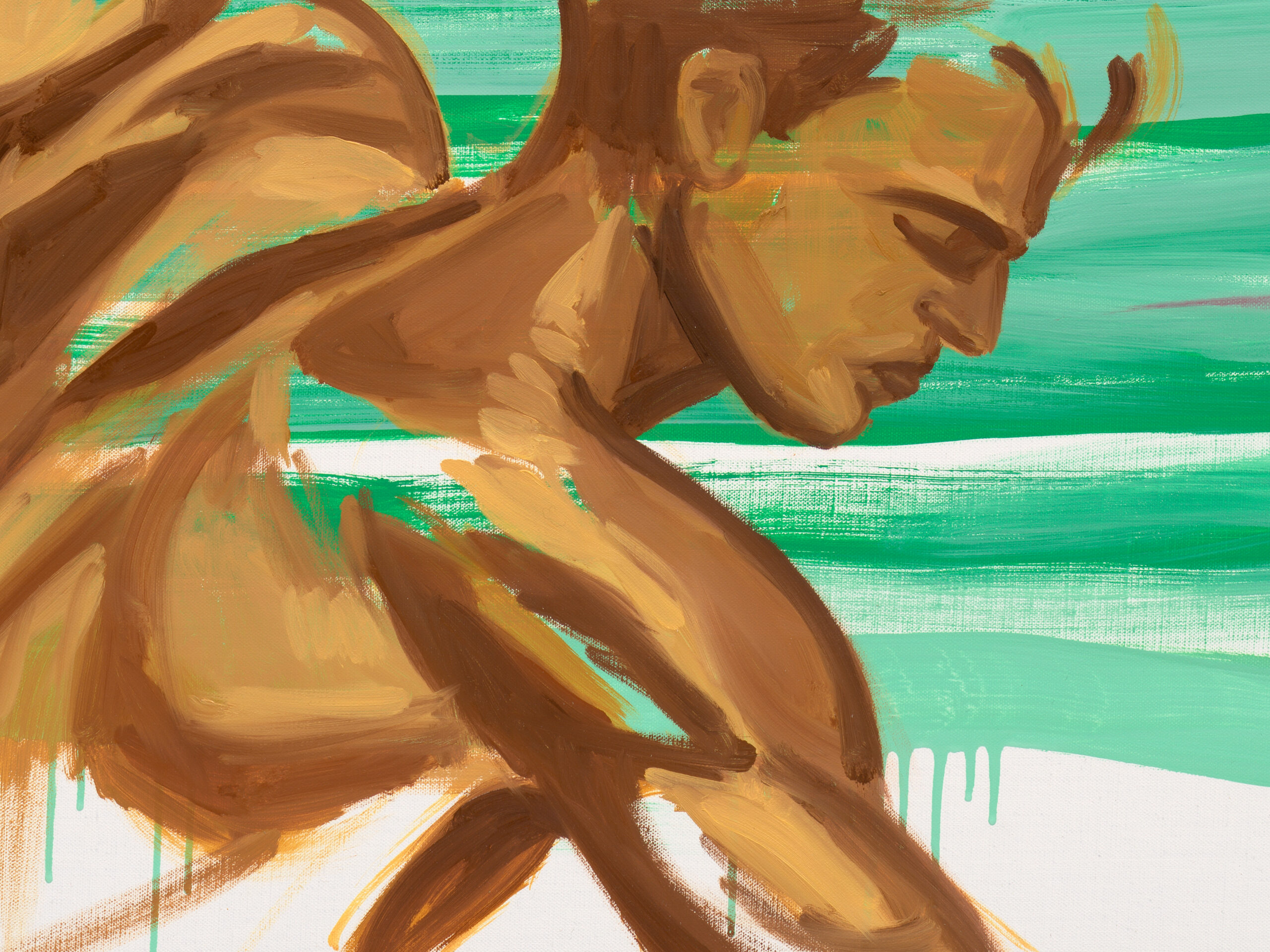

There are, in the studio, two unfinished paintings in the style most recently deployed by Salle, most recently on view in the exhibition World People at Lehmann Maupin in Seoul. I would describe this style (indeed, I am describing it) as being oppositional and defiant, as well as pointed, slightly garish, droll. Each painting comprises two canvases or panels, one greater in height and more figurative, one lower and more abstract, so as to evoke something of a clash between appearance and action. Salle, of late, has drawn inspiration from the oeuvre of the famous New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arne, and clippings of Arne’s work are scattered on a table piled high with various reference images. On the shelves along a half-wall are even more, and lots and lots of monographs: Mona Kuhn, Martin Kippenberger. Also, a book of Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests and another about gardening. I open a Rose Wylie monograph to a page featuring a painting of two loony swimmers, which someone, either Salle or an assistant, has bookmarked with a sticky note. Recently, Salle wrote a long piece about Wylie’s work for the New York Review of Books, where he is a longtime contributor. It was a very good piece, with several lines that were memorable, or that I remembered not only because I had read the piece an hour ago in the car but because they were sharp. “Painting is fundamentally a matter of a translation,” for example. Another: “Her subject is simply whatever catches her eye.” The sticky note just has the word color.

“You can’t take pictures of the books,” says a voice out of nowhere. I turn to see a small-ish man with a crisp, tanned face, wearing a light button-down and some kind of pants and nice sandals. There is something about the scene, the pacing, the lighting, the gloom of the day, that makes me feel like a detective, as in a Chandler novel. Rather, you know, as if I’ve been hired by someone mysteriously wealthy to find a Ming Dynasty vase or a lascivious wife.

Outside my head nothing is missing, nor is there any real mystery to the wealth on display: “I feel I can say what I want about him,” Rene Ricard wrote of Salle in a 1981 issue of Artforum, “because his pictures cost so much money I can’t hurt them.” Salle the painter is almost as fortunate. He has worked without interruption for over three decades, during which time his paintings have sustained a lot of critical damage while his ability to paint remains wonderfully the same as it ever was.

———

SARAH NICOLE PRICKETT: How long have you lived here in the Hamptons?

DAVID SALLE: I never remember dates, but I think I’ve been here since 2008 or 2009.

PRICKETT: If you don’t remember things by date, you remember by…

SALLE: Era.

PRICKETT: What was 2008?

SALLE: The era of the crop top.

PRICKETT: Speaking of eras, you’ve lived through a number of deaths of painting.

SALLE: It comes to the fore periodically because of a stylistic hegemony that leads to the perception of a dead end, even if painters don’t feel that way. When I was a kid in art school, I asked the dean why abstract expressionism died. He looked at me and said, “Exhaustion. It just wore itself out.”

PRICKETT: Except individual paintings are meant to last forever.

SALLE: But when you say “death of painting,” that presupposes a cultural agreement, regardless of the individual painters.

PRICKETT: Yeah. It also presupposes a life of painting, which is maybe too animistic.

SALLE: Well, let’s put it in one simple sentence. Slogans are not paintings. And paintings are not slogans.

PRICKETT: Very good. Though, you do love Christopher Wool! I love Charline von Heyl. Their marriage is so interesting to me.

SALLE: Yeah, she’s terrific.

PRICKETT: Her paintings move. In your interview with Emma, you talked about the object being in a fixed position at a gallery, and you were saying, “We haven’t figured out a way to bring the paintings to the viewer, such as on a conveyor belt.”

SALLE: I don’t remember that at all.

PRICKETT: You don’t have to, but there are painters whose paintings do seem to approach you. I remember I was at MoMA for an exhibition of hers and it was arranged in this old-fashioned, salon way. Her painting was off the wall, not hung, and I remember seeing it peripherally and being startled by it. I felt like it was leaping.

SALLE: You’re referring to the Amy Sillman installation? It was highly unusual and in my opinion, fantastic. I was recently talking to an artist about how subject-object relations are different in other cultures. In a way, you’re the subject. It implies a completely different relationship to the object where the word “object” would not even be appropriate.

SALLE: Right, the real subject is the presentation itself.

PRICKETT: You talk about the inside energy of a painting, which I think is a phrase you got from a friend of yours. What does that energy mean to you in a painting?

SALLE: It’s my friend, Alex Katz’s phrase that I’m borrowing. When you bring your awareness as a viewer to that idea, you then start to look at things slightly differently. Certain things are just programmatic and executing an idea. That doesn’t disqualify them from having inside energy, it could mean they’re simply not listening too much to the outside world. But when someone makes a painting that evidences thinking, it’s not obvious and it’s not the norm. I’m not a philosopher, but you know when you see it.

PRICKETT: You are a little philosophical. Inside energy reminds me of [Henri] Bergson. He has this thing about intuition versus analysis.

SALLE: I think a painter does both, simultaneously.

PRICKETT: In your book, when you say you should just stand in front of the painting and see what it makes you think about, as opposed to what you feel you should be thinking about, that is kind of a Bergsonian intuition of allowing for absorption. How much the inside energy of a painting has to do with the viewer’s own inside energy?

SALLE: I think they’re two different things. As I said, intuition and analysis go on simultaneously. It’s a physical thing with physical properties, so we’re responding to the vibrational quality of what was made.

PRICKETT: When you say vibrational, that’s more metaphysical than physical, isn’t it?

SALLE: I think it’s just optical.

PRICKETT: I see. Have you always been good at talking?

SALLE: I don’t know, ask other people.

PRICKETT: You’re married to an analyst?

SALLE: We just got divorced, but I’ve been surrounded by analytic culture a fair amount of my life.

PRICKETT: Yeah. You were born in the Midwest, not a hotbed for analytic culture, but do you have analysts in your family?

SALLE: [Laughs] No, quite the opposite. I didn’t know what the term meant when I was growing up.

PRICKETT: Neither did I, but I love the children of analysts. Why is the idea of having analysts in your family funny?

SALLE: It wasn’t the kind of family where that could have occurred.

PRICKETT: When did your attraction to psychoanalysis develop?

SALLE: I was curious about it from a young age. I grew up in a time where it was almost a comedic set piece, like the Nichols and May comedy routine.

PRICKETT: And you’re an analyst to this day?

SALLE: No. I haven’t done it for a long time.

PRICKETT: In the press release, there’s something about the chaos of abstraction.

SALLE: I’m not sure I even know what that means. We are living in the era of the artist’s statement, but on this one, I did not have any input. Sometimes I do.

PRICKETT: I think it probably came to mind for whoever was writing the press release because Genesis, in Christian myth, is the naming and ordering of things. And chaos is the void before language. There’s no embrace of chaos in the Bible, but in Greek myth, chaos is primordial, genderless, airborne, or maybe air itself.

SALLE: There has been a tendency, since I first started showing my work, to talk about it in these terms. “Media overload” was the preferred term for a number of years. Chaos doesn’t sound the same, but it kind of means the same thing, which to my mind is a misreading. Whenever there’s a certain degree of complexity, the default response is to describe it as chaos or overload or circuitry, but that could just mean that people aren’t very attentive.

PRICKETT: In the ’80s and ’90s, did you often feel misread?

SALLE: Well, I haven’t taken a survey, but my suspicion is that many of us, if not most, feel misread. There’s a lot of categorizing and familiarity, but that’s different to understanding. Which artists are really understood? I don’t think many. It’s a condition that we all labor under.

PRICKETT: Is that part of why you started to write?

SALLE: Possibly.

PRICKETT: Rene Ricard writes about Julian Schnabel in Artforum, and he recalls admiring a painting with an acquaintance. The acquaintance says dismissively that what Ricard is responding to is just the way the paint is put on, and Ricard responds, “What else is there?” I think about it a lot.

SALLE: Rene was right. I don’t know what else people think ought to be there. I remember getting into a little bit of an argument with this guy when I was a visiting teacher, where I was describing what I thought was going on in a painting and he said, “That’s just formalism.” So I said, “With what do you propose to replace it?”

PRICKETT: It’s about the content or it’s about intention, which is something you talk about a lot.

SALLE: Right. There’s either the visual thing or all the other stuff, and you can decide which one creates meaning for you, but they shouldn’t be confused, in my opinion. It’s more rewarding to get to the meaning through the formal properties of whatever’s going on in the painting, and more apt to be true.

PRICKETT: Yeah, although you can never jettison context. If only you could see every painting as if seeing a painting for the first time.

SALLE: I don’t think that saying “just look at the painting” is ignoring context, but I think that these approaches are themselves subject to fashion. Those fashions change, like fashions do. Certain approaches have become over-emphasized. So of course, context is part of the story, but to think that it creates meaning entirely is a mistake.

PRICKETT: It’s just that every painting is already so laden with the meaning of what a painting is.

SALLE: I’m not trying to refute what you’re saying.

PRICKETT: No, you can.

SALLE: I’m just not sure I feel that way.

PRICKETT: Probably because it’s demystified for you.

SALLE: Well, it’s more than that. I think too much attention has been paid to context as a meaning determinant. That sounds so academic, it’s not usually how I talk, but I’ll give you an example. I was teaching this class at the Bruce High Quality Foundation art school. I don’t know if you remember those guys. One of the nice things they did was that their art school was free.

PRICKETT: Which no art school is anymore.

SALLE: It met in a second story room on 1st Avenue above a TaeKwonDo studio. It was very funky and fun. They asked me to do a class on writing about art, because that area in our culture seems to need help. We had so many people sign up for the class, it was kind of a free for all. I assigned them to go look at a show and write about it, and many of them started with how much they didn’t like the ritual of getting in the museum. And I said, “No, talk about the painting.”

PRICKETT: Did you ask the students why they felt that that part of the experience was important to write about?

SALLE: I know why. They were not prepared to discuss the work.

PRICKETT: Because people feel insecure in relation to art. Galleries are all free and anyone can go into them, but anyone doesn’t. I don’t know all the reasons why people feel intimidated. You could say the expense or the sacredness of it. But to me, it seems like what your students were doing was apologizing at the beginning of the piece for everything they were going to say after.

SALLE: That’s one way of putting it. My point is that your lead shouldn’t be, “I walked the museum.” The editor’s going to cut that. Your lead is, “This artist does X.”

PRICKETT: Can you recall some early experiences with works of art that you perceived to have this inside energy that were particularly meaningful to you?

SALLE: I feel my life is made up of those experiences, but to cite just one, I remember going to a show of Jasper Johns in the Castelli Gallery and it was a show of crosshatch paintings called “The Dutch Wives” series. It raised the problem of, “How does he do it? How did Jasper get this palpable sense of thinking into painted circles?” I had that hard confrontation with it, that moment of coming up against something resistant and frustrating but also swooningly beautiful and lyrical. It floored me in such a fundamental way, and those simultaneous feelings were what I was looking for in art.

PRICKETT: There’s also the question of presentation, and whether something is more presentative versus recessive.

SALLE: I use the word presentational.

PRICKETT: There we go.

SALLE: Putting a painting on the wall is presentational by definition. However, some things have a presentational character.

PRICKETT: Of course. There are times that you’ve been both kinds of artists. You’ve worked for such a long time and the way you’ve worked is very consistent, but what you’ve produced is variegated and almost argumentative with yourself. You’ve gone through periods of getting a lot of attention and other times maybe not enough. How important is it to you for people to be paying attention at all? Do you get sick of it? Do you wish for more of it, less of it, or try to forget about it altogether in order to work?

SALLE: That’s a very good question. I would say in general that if too much attention is bad for an artist, not enough attention is probably worse. Neither is really that great, but the absence of attention is challenging if we think of art as a communication between people. If it’s purely one-way, that gets pretty hard to sustain. But assuming that everyone’s waiting for your latest masterpiece is also not a very productive place to be. Maybe the trick is to keep a balance between the two extremes. It goes back to your earlier question about being understood. Is it better to be liked by a large number of people or to be understood by six people?

PRICKETT: I would be surprised if being liked were your priority.

SALLE: Well, maybe it is for some people. It’s not mine.

PRICKETT: Yeah. It’s like, do you have plants in your house?

SALLE: I only have one plant in the house. I think it’s a lemon tree. I have a lot of plants outside the house.

PRICKETT: I think of attention as being like sunlight for a house plant. When I was younger, I learned the hard way that there is a limit to how much attention you can withstand in the social world, despite what you think that you want.

SALLE: If you think of it as sunlight for a plant, it’s pretty essential.

PRICKETT: I think everybody has a different inborn tolerance. Some people can withstand, and sometimes even demand, constant attention. The same way that some plants thrive in Florida and other plants thrive in Alaska.

SALLE: I should write that down. That’s a good line, the Alaska horticulture. It just comes down to personality.

PRICKETT: And for you, are you thinking of a painting as something here in your studio, not thinking about its destiny in the marketplace?

SALLE: I might think about it, but it doesn’t help me figure out the painting. Since you raised the question of analysis, the thing you learn in analysis is that the detective work almost always leads you to a place that you did not expect. Often it turns out the story is actually quite different, maybe even the exact opposite, of the reality, and what I think about painting is not unrelated.

PRICKETT: Are you telling yourself a story while you’re painting or are you imagining telling it to other people? Some artists are completely alone in their studio and others have the onlookers always with them—audience, buyers, whatever.

SALLE: It’s nothing to do with that. Painting is an activity between you and the canvas, but you’re aware of it being seen. It’s not just a private conversation. It’s a private conversation in a way that’s meant to be overheard.

PRICKETT: Can you point to an element of the painting that you did not plan on painting?

SALLE: I didn’t plan on much of it, but I think the painting hinges on a fulcrum point. And what is that fulcrum point?

PRICKETT: I would love to know.

SALLE: The fulcrum point is over overpopulated versus underpopulated. Overcrowded versus sparse. Let’s say you think the painting is overcrowded, so you consolidate and eliminate things, but when you stand back you realize that it actually functioned because of its overfullness. And by doing the rational, sensible thing you spoil what was interesting about it.

PRICKETT: Yeah, there’s a lot going on, but it’s also very harmonious. What’s the ratio of this canvas?

SALLE: Oh, I don’t know. When the series first started, it was a more strict function of these different elements. The tree divided the canvas in half. The lower panel signified the roots of the tree penetrating the surface of the earth and going underground, which was clearly a metaphor for the past or shared history. Over time, in some cases the roots went away altogether, but we still had this over-under diptych where the proportion itself seems to imply a certain underground.

PRICKETT: If you were to draw a horizon line across the painting you would have earth and something else below.

SALLE: More earth.

PRICKETT: Yeah. Oh, right, because you’re Jewish, you don’t believe in hell. There’s no real term for it. You can’t call it a sub-painting. Let’s just call it the B painting.

SALLE: In classical art history, they call it a pradella.

PRICKETT: Really?

SALLE: It’s a word that means “companion of.”

PRICKETT: Pradella. I love learning new words, but it’s so violent comparatively.

SALLE: Okay. What other questions do you have to grapple with? You’re asking such big questions.

PRICKETT: What I really want is to ask if I can watch Search and Destroy, the film you made in 1995? I can’t find it online.

SALLE: Yeah, my studio manager found a DVD. I don’t know if you have a way to play it, but she has a DVD for you.

PRICKETT: Amazing. When was the last time you saw it?

SALLE: A long time ago.

PRICKETT: Did you make a short film about JD Salinger, or did you just say that you wanted to?

SALLE: I never finished it. I shot it and I probably edited it about 90%, but I don’t know where it is.

PRICKETT: Do you have a lot of unfinished work?

SALLE: Yeah.

PRICKETT: So film, painting, collage.

SALLE: Collage is a separate activity. Collage is just a way of making stuff.

PRICKETT: Everything is a way of making stuff.

SALLE: Yeah, but don’t say I’m a collagist. It’s not a job description.

PRICKETT: Neither is painter.

SALLE: Well, I beg you to differ with you there.

PRICKETT: How is painting a job and collage not? Do you think painting includes collage?

SALLE: If you want it to.

PRICKETT: My mom cuts things and glues them, and this too is painting because of the application of liquid to a flat surface?

SALLE: No, collage is just a way to build an image. Its original meaning is to add things from the world in a painting as in the Picasso cohort of the 20th century, like the rough around the wine bottle added to a painting. That was a collage. And then, little by little, it became things that people do when they’re in their dorm.

PRICKETT: None of this has anything to do with my question, which is about being a total artist. I don’t know where this idea comes from, but I associate it with a lot of extreme nationalists like Wagner and Italian futurists. There’s an idea of the total artist being somebody who can almost remake the whole world. You know what I’m saying?

SALLE: Yeah.

PRICKETT: Is this an aspiration you share?

SALLE: Not necessarily. Some people are really, for whatever temperamental or situational reasons, focused on one aspect of art making, and others are more restless and maybe have a shorter attention span or simply are curious about different things. Sometimes it’s a question of opportunity. A lot of things that I thought about doing, I haven’t done.

PRICKETT: Like what?

SALLE: For a long time I’ve been interested in animation, but I’ve never taken the time to do it until very recently after 40 years of thinking about it. Now these things are much easier because of technology. So sometimes you don’t do things for lack of opportunity and sometimes you are given an opportunity to do things that maybe you wouldn’t have otherwise. Why did Picasso spend so much time making ceramics? He went to the place in the south of France where they do all the ceramics and someone said, “Hey Pablo, come by the studio one day and see what you think.” And sometimes you can do things that are against your nature or uncongenial to you.

PRICKETT: This is what I was talking about before about being in argument with yourself, or an argument with the way that you’re perceived. It also has to do with the marketplace, not wanting to be pinned down or packaged up too easily. Changing your style or your medium goes against the algorithm for success that a lot of young artists follow. I have a friend who paints nudes of herself and she’s so sick of it, but every time she tries to paint something else her gallerist or whoever will say to her, “What people really want is the full frontals.” People get boxed in and it takes courage to resist the algorithm.

SALLE: “Resist the Algorithm.” There’s your title.

PRICKETT: That’s what you want the title of the piece to be?

SALLE: It could be. I think it’s a really good title.

PRICKETT: David, I’ll make a note of that. But you know what I’m saying. Maybe resistance is too politicized now.

SALLE: A good artist has to navigate all these different inputs of information. A gallerist wants X, the audience wants Y, you want Q.

PRICKETT: And one thing you want is for the audience not to get what they want all the time. For people to have to look again and think again.

SALLE: I don’t think the audience is monolithic. The audience is comprised of individuals. If you’re a strong artist with a strong identity, you find your way.

PRICKETT: Do you perceive yourself as having a strong identity?

SALLE: Well, you mentioned something earlier about diversity of style. On the surface level, if you look at 40 years of painting, there’s quite a range of stylistic diversity, and yet there’s something that links them all together, not just conceptually, but energetically and visually. That quality is a constant that you can’t do anything about. You can’t change it if you wanted to. The way you hold the brush and the pressure on the brush determines the quality of the mark. Those things remain much more consistent than not. That’s simply the nature of making. You merge with the painting in a funny way, and then the painting separates from you. You separate from it, then you come back to it and realize maybe you haven’t really moved all that far after all. For a long time, I wasn’t intending to do this, but at the final stroke of combinatorial electricity that the painting was aiming for, the energy was transformed into a kind of melancholia. And even if I tried not to, it always ended up in that vibrational mood. Someone was here recently, an older woman who came for a studio tour, and the first thing she said was, “Oh my god, these paintings are hilarious.” And I said, “Oh, thank you.” So either the work has changed, or she’s one person who has one opinion and other people have different opinions.

PRICKETT: They are kind of funny in a Nichols and May way. Do you think of yourself as melancholic? You don’t seem that way.

SALLE: Not particularly.

PRICKETT: No.

SALLE: I don’t think that one is like one’s work in that way. I think one is one’s work, but that’s not the same thing. You don’t need to be melancholy to make melancholy paintings. I’m a kind of happy guy in general.

PRICKETT: Do you have your work in your own house?

SALLE: I do in the city. I don’t think I have anything here.

PRICKETT: Whose art do you have in your house?

SALLE: A whole bunch of people. A nice little painting of Charline. I have a couple of things of Cecily [Brown], my friends. I’m terribly sorry, but I don’t have a lot of time left because I have to go to the North Fork for a concert.

PRICKETT: For a concert of what? We can be done.

SALLE: Oh, it’s a Perlman student concert that Barbara Gladstone sponsors every year, this summer music camp on Shelter Island. Young people come and spend the summer there working on their concert skills and then they give a concert at the end.