Colman Domingo woke up naturally at 3:30 in the morning on the day Oscar nominations were announced. He was jetlagged, having just returned to L.A. from Europe. He looked up at the moon and felt that, despite the darkness of the fires and the country’s crazy politics and everything else going on — no matter what happens — the moon was there, and he was blessed.

Two hours later, he found out he’d been nominated for his soul-baring performance in “Sing Sing.”

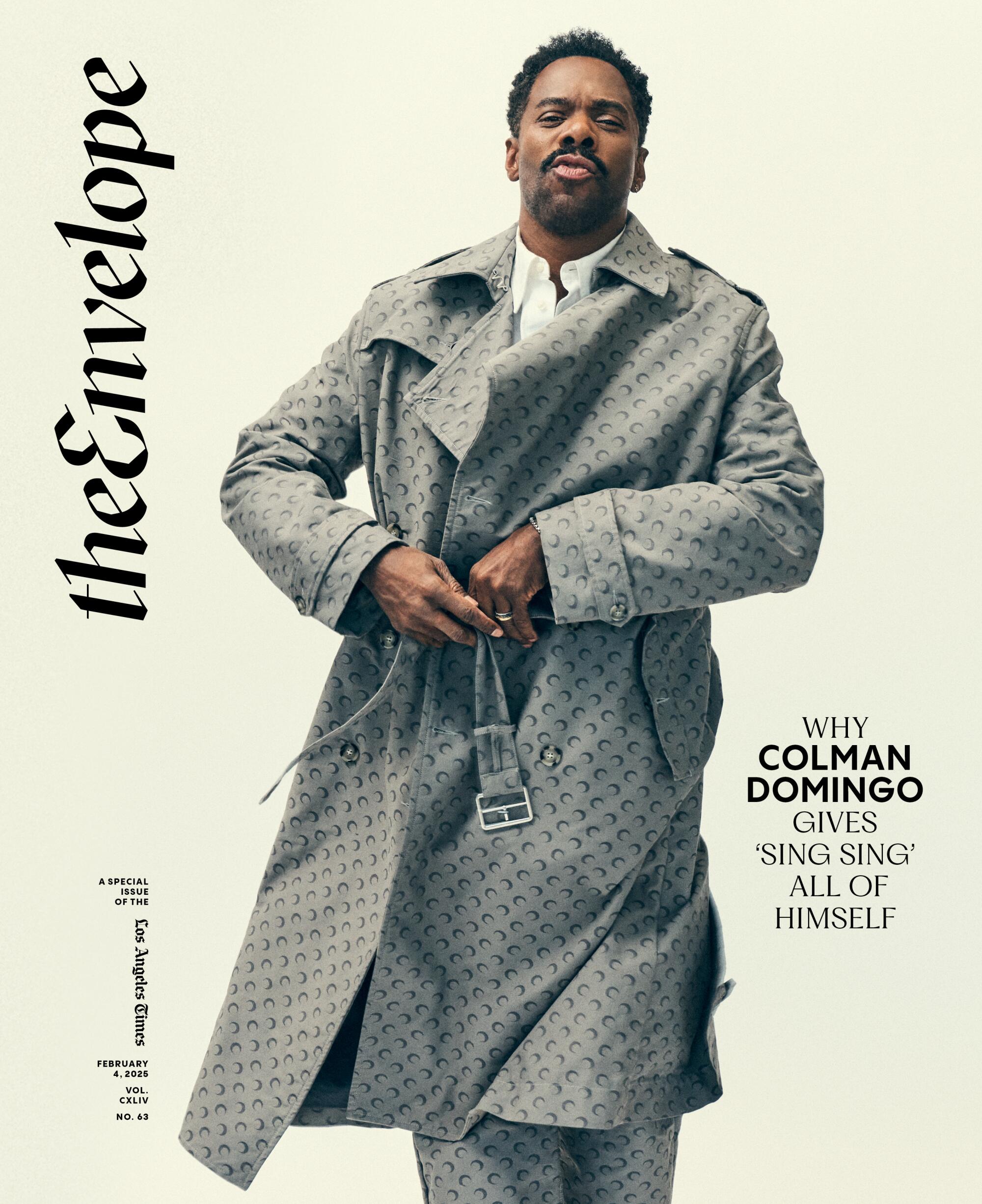

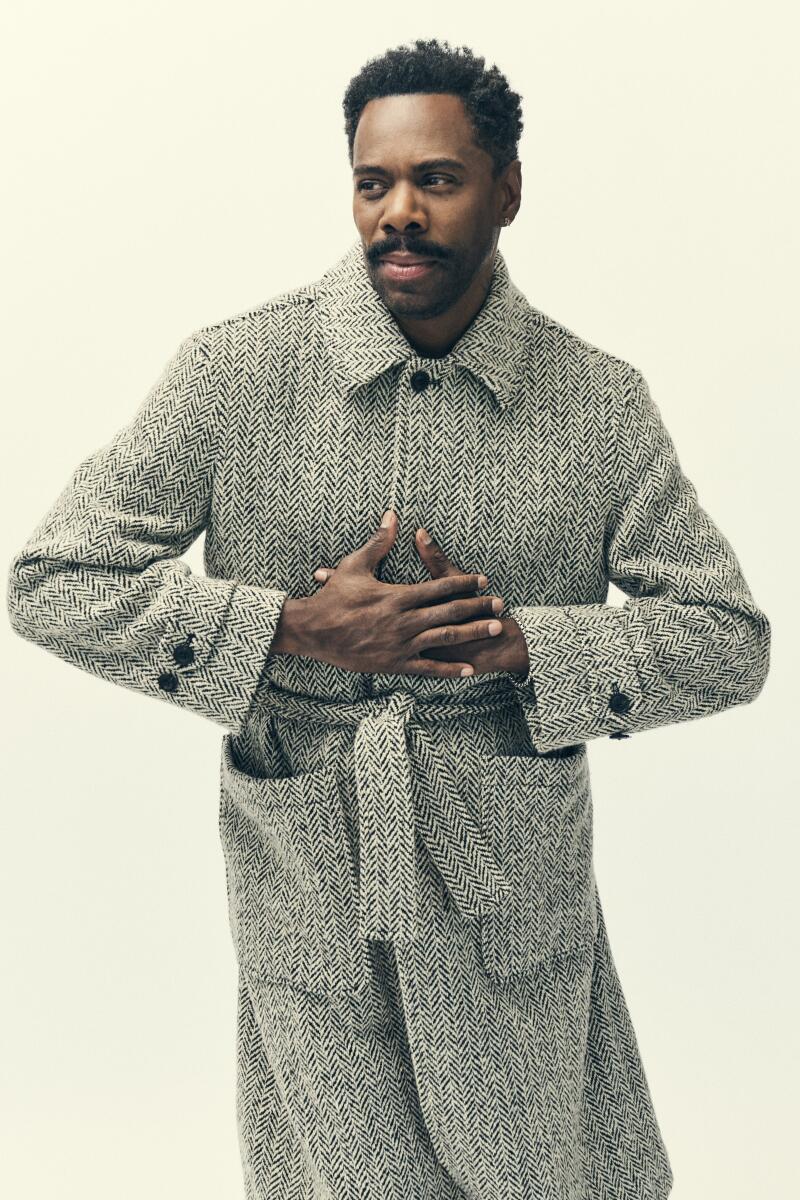

We met just a few hours later at the sky-scraping offices of A24 in West Hollywood, where Domingo — 55, impeccably dressed, wide awake and in good humor — was waxing thoughtfully about the power of Shakespeare.

Colman Domingo, Sean San Jose and the cast of “Sing Sing.”

(A24)

“Shakespeare is someone who gives people confidence, I think, when it comes to language skills,” says Domingo, a Philadelphia native who has been acting for 34 years and who has done his fair share of board-treading with the Bard’s work. “I think why I’m not afraid of language in my work is because I’m rooted with a lot of Shakespeare. … He’s giving you such great jumping-off points to create whole worlds with language.”

He ponders it a little more, and adds: “I think Shakespeare would be a good buddy of mine. I think we’d have a couple beers together, and a good laugh.”

When I mention that I’ve always struggled with Shakespeare because it feels like a foreign language, Domingo launches into a fully committed and physical recitation, from memory, of a passage from “A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream” — about hopping fairies and blessing this palace with sweet peace.

“You understood that, didn’t you?” he says when he finishes, a twinkle in his eye, and it’s suddenly clear just how much of himself Domingo poured into his role in “Sing Sing.”

His character, John “Divine G” Whitfield, opens the film with another riveting speech from “Midsummer’s” — Lysander’s monologue about how “The course of true love never did run smooth” — which, the actor says, “tells you a lot about the character in the very first sentence.” Whitfield is a very real person, formerly incarcerated and the product of the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York. In conceiving his performance, Domingo saw Divine G as “the best of that program and what it can be.”

“When I was examining his level of skill,” Domingo says, “I thought: ‘He’s just a very raw actor. Not polished.’ … But imagine if that raw talent was polished — it could be useful outside of the walls. You know, he can actually make a career for himself. Which is what my co-star, Clarence Maclin, is doing.”

Maclin, a.k.a. “Divine Eye,” plays a version of himself in the film, which he also co-wrote. He is one of several former inmates and RTA alumni who play themselves alongside Domingo and a handful of professional actors, lending the whole production a powerful authenticity. It also forced Domingo — who had very little time to prepare to shoot the film in 18 days, between doing “The Color Purple” and reshoots on “Rustin” — to be more of his actual self than he’s ever been onscreen.

“I knew there needed to be sort of a sleight-of-hand,” he says. “But also, if I’m dealing with guys who had the real lived experience, and they’re bringing themselves and playing versions of themselves, to a certain extent I had to play a version of myself. I had to bring myself in every single way.”

Clarence Maclin and Colman Domingo.

(A24)

For that reason, it’s hard for him to watch the film. He’s seen the movie only twice; once in a rough cut and then again on an airplane. “When I would start to watch it, something would come up in me,” Domingo says. “I’m like: ‘I’m too emotional, and I can’t watch.’ And I had never felt that way about anything I’ve watched of my own — because usually I’m building a character. I think I felt too exposed,” in “Sing Sing.”

In the film, Divine G is the de facto leader of a group of men who stage plays at the maximum-security prison. He’s a talented thespian who also writes plays; a gentle man, a mentor and a self-described jailhouse lawyer who is preparing for his parole hearing. He recruits the much rougher-edged Divine Eye to join the RTA program, and despite their very different temperaments and Divine Eye’s initial resistance to the vulnerability and unguarded emotions the program elicits, they become unlikely friends.

In one scene, Divine Eye calls Divine G the N-word, and Divine G says they don’t use that word inside the group — instead, they call each other “beloved.” This was, in fact, a lesson the real Divine Eye taught Domingo during one of their Zoom rehearsals, and Domingo insisted they work it into the script.

“He said it just so carefree,” Domingo says. “And I was like: ‘Grown, tough, strong men in prison call each other “beloved.” ’ ” It was said so casually, Domingo notes, and yet was so impactful. “I thought that was key.”

“Sing Sing” illustrates the profound power of acting and the arts to heal the cracked and hardened hearts and bodies of men locked behind bars. It does so without preaching or grandstanding, with the most gentle touch and feathery 35mm cinematography by Pat Scola, who chose to use natural light and to focus on the “landscape” of these men’s faces as they alternate between parading in silly costumes and quietly visualizing their happiest memories.

Clarence Maclin and Colman Domingo.

(A24)

“I think it has a grace to it,” says Domingo, “a grace and an intelligence and a tenderness. And nothing about it is being an activist or political in any way. If anything, it’s the antithesis of that. It’s very human — so therefore it does become political, because you’re dealing with the people. So it takes care of that by just going more micro.”

Much of the film was shot in two real prisons — including Downstate Correctional Facility in upstate New York, which had just been decommissioned two weeks before the cast arrived.

“So every ounce of it was very real,” Domingo says. “The way the air did not flow. The cells. The colors. The layout of the land, where you can’t find your due north because it’s just set up that way. And you thought about what that does to you psychologically. And then you thought: ‘Well, this doesn’t feel like a place where anyone can heal or get better or contribute.’”

For Domingo, putting on prison greens (which he wanted to be a little ill-fitting) was just another costume, but for his castmates it was a true act of courage to get back into clothes, and an environment, from which they hoped they had been permanently freed — “but I know that they knew the impact it could have, a film like this,” he says.

Still, even he needed a bigger emotional safety net to do this project, which is why he requested that Sharon Washington play the parole board officer and Sean San Jose his fellow inmate, Mike Mike. “Those are my two closest friends on the planet,” says Domingo, who has known San Jose since the mid-’90s, when they were young actors together in San Francisco, bringing plays about the AIDS crisis to Bay Area students. He needed them, he says, because they “really held that space for me to be as vulnerable as possible,” he says. “They know my heart.”

Colman Domingo and Clarence Maclin.

(Dominic Leon/A24)

There’s a pivotal scene, midway through the film, where Divine G comes to his parole hearing with a stack of envelopes and evidence, confident that a newly found recording will exonerate him from the murder that wrongly sent him to Sing Sing.

“He’s hopeful, and he’s open, and he’s also vulnerable,” Domingo says. “He’s all the things that the program has built him to be. There are trust exercises in the theater, so I think he’s being trusting that this person will meet him where he’s meeting them, with the truth. But he almost forgot, I think, that he’s up against the cynicism of the world.”

It takes just one question from Washington’s character — asking if his sincerity in the interview is actually a performance — “to just derail him, to take something that he’s been using as his soul work, and to question it,” he says. “It just dismantles him right there.”

Domingo didn’t plan how to act that scene, but running smack into the harsh reality of the system, the actor visibly deflates. “I tried to say something, but I had no words,” he explains. “Someone who always has something to say is rendered speechless.”

This heartbreaking moment, compounded by another tragedy, causes Divine G to lose hope, and he becomes very quiet and almost catatonic when he’s back in rehearsals for the upcoming play — “I think because there’s a volcano deep inside, and also an abyss,” Domingo says. “I think he’s someone who has hung on and clung to faith and hope in art. And his hands can’t cling anymore. So he just goes to zero.”

In that state, the slightest disturbance — someone in the program taking his props, someone forgetting their line — sets him off, and Divine G erupts.

“It gets me emotional to think about it,” says Domingo, “but it’s like, this man’s life has been ruined — and many other folks’ too who’ve been wrongly incarcerated. And you feel like you’re just a plaything for life. And at some point, he’s like: ‘I can’t take it anymore.’ Even this gentle man will fall apart and get angry.”

After a shocking outburst and withdrawal, he is finally able to come back to the light thanks to the lessons of tenderness and compassion he’s been imparting to Divine Eye. In the film’s final scene, when Divine G has finally been released, Domingo walked up the road leaving the prison, again, he says, not premeditating how he would react when he saw Maclin waiting to greet him. That scene had been rewritten many times, “overwritten” in Domingo’s opinion, and he asked: “Can we just try one without those words?”

The director, Greg Kwedar, said: “I’m going to trust what you and Clarence do.”

Domingo’s mind and heart were filling up with the character’s reality: Having been locked up for 25 years, he’s coming out to a world where his mother is gone and he doesn’t know who, if anyone, will be there for him. That’s when Maclin opened his big, manly arms for a hug.

“No, no, no, no — not with the weight of 25 years and what he’s thinking,” Domingo thought. “No, please don’t. I can’t. I can’t. I can’t. All that he’s been holding, all that he’s been holding. Clarence hugs me — and the sound that came out of me is a sound that I know I’ve only heard one other time out of my own body. And only people who understand this know that sound. It’s a guttural sound, and it’s a sound when you lose someone very dear to you … like when I lost my mother. It’s a sound that I never want to hear again come out of my own body.”

“Sing Sing” director Greg Kwedar and Colman Domingo.

(Phyllis Kwedar/A24)

But for Domingo, “Sing Sing” was worth the cost of how much he gave of himself. It’s a film that delights in the rare beauty of seeing adult men cry together, of trusting their hearts to each other and of recovering the childlike joy of play.

He tells me an anecdote about a young woman who said she started bawling when Sean Dino Johnson — one of the real former inmates — rolls around on the floor playing with a sword. He asked her why, and she said: “Because it’s something I wish for my father, for my brother, to allow themselves to play and be vulnerable, and how beautiful that is, and how that helps everybody.”

Domingo says this film is the most significant thing he has ever made. “It’s something that can really shift people’s hearts and minds,” he says. “It really can.”