Greek pop music of the 1960s is not an area of musical history where anyone who doesn’t fondly remember it first-hand is advised to dwell. There are a few exceptions – garage rock collectors have unearthed a string of obscure, impressively raw singles by the Stormies, the Persons and the Girls – but the archetypical mainstream Greek response to the rise of the Beatles might be Vangelis Papathanassiou’s band the Forminx, who dealt in novelty instrumentals, weedy Hellenic-accented stabs at Merseybeat and a side order of lachrymose balladry.

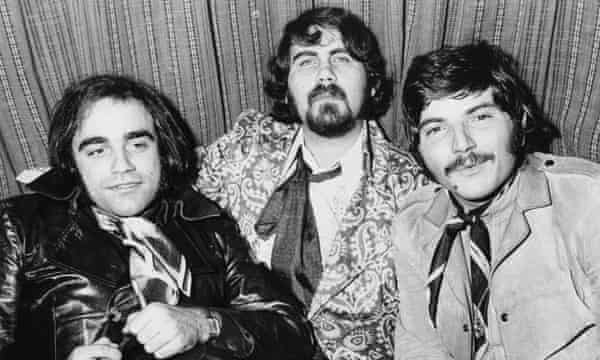

The Forminx were successful in Greece, but it clearly wasn’t enough for Papathanassiou, who claimed his earliest musical endeavours involved experimenting, John Cage-style, with the sound of radio interference. After the Forminx broke up, he took up a career writing film scores before forming Aphrodite’s Child with another refugee from the Greek beat scene, singer and bassist Demis Roussos.

They were a completely different proposition from anything that had emerged from the country before, a product of the anything-goes atmosphere engendered by psychedelia. Their first two albums, End of the World and It’s Five O’Clock, offered a vast range of styles that had sprung up around the summer of love, from droning raga-rock on The Grass Is No Green to A Whiter Shade of Pale-inspired balladry on It’s Five O’Clock’s gorgeous title track; from You Always Stand In My Way’s heavy riffing to Mister Thomas’s mock vaudeville. Crucially, they didn’t just sound like a pale imitation: Roussos’s vocals – high, tremulous, but powerful – clearly weren’t from an Anglo-American rock tradition; nor was their use of bouzouki. In fact, Aphrodite’s Child occasionally didn’t sound like anyone else, as on the amazing warped funk-rock of Funky Mary.

This uniqueness was underlined on their masterpiece, 1972’s astonishing double concept album 666, which delivered 77 minutes of wildly experimental music that touched on jazz, proto-metal, prog and stuff that still defies explication: it’s variously becalmed, richly melodic, punishingly heavy and, on ∞ (Infinity), unsettling. It was an incredible achievement, but it attracted less attention than the band’s earlier European hit singles. In any case, by the time of its release, Aphrodite’s Child had split, the other band members apparently unhappy with the increasingly avant-garde direction Papathanassiou’s music was taking.

Roussos subsequently became a huge MOR star; Papathanassiou’s fantastic 1973 solo album Earth continued in 666’s eclectic vein, skipping from slinky funk that would subsequently be claimed by Balearic DJs (Let It Happen) to the pounding Come On, to We Are All Uprooted, an eerie, drum machine-driven track that seemed to address Greeks who, like Papathanassiou, had fled the country in the wake of the 1968 military coup.

In a sense, it was a shame he didn’t make more albums in that vein, but his attention was increasingly attracted by soundtracks and synthesisers: he relocated to London, built a studio in Marylebone and started scoring films and releasing electronic concept albums that positioned him as a kind of Greek equivalent to Jean Michel Jarre or Tangerine Dream, albeit of a more dramatic, grandiose bent. Something of 666’s apocalyptic intensity lingered around 1975’s Heaven and Hell, and Odes, the album of Greek songs he recorded with actor Irene Papas (although 1979’s album China and his acclaimed soundtrack to the nature documentary Opera Sauvage were easier on the ear).

He also unexpectedly developed a parallel career as a pop star, in the company of Yes vocalist Jon Anderson, an Aphrodite’s Child fan who had contributed to Heaven and Hell and Opera Sauvage. The three albums they released as Jon and Vangelis deftly bridged the gap between prog rock and the vogue for synth-pop. The songs were often long (the title track of 1981’s The Friends of Mr Cairo lasted the best part of 15 minutes) and, as always with Anderson, the lyrics tended to the opaque and ponderous – but Papathanassiou’s music was richly melodic and the sound of Anderson’s high voice in an electronic landscape was appealing. I Hear You Now, from their first album together, Short Stories, and I’ll Find My Way Home, from The Friends of Mr Cairo, were British hit singles, but their most lasting track proved to be the emotive State of Independence, from the same album, and subsequently alighted on by producer Quincy Jones and covered, brilliantly, by Donna Summer.

By the time Anderson and Papathanassiou’s partnership ended in 1983, the latter was also a star in his own right. His breakthrough came with his Oscar-winning soundtrack to Chariots of Fire. The soaring, valedictory feel of its theme – another hit single, inescapable in 1981 – fitted the movie’s mood so well that the anachronism of having a film set in the 1920s soundtracked by 80s electronics passed almost unnoticed. His subsequent soundtrack to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner was even better. Murkier, more abstract and far more emotionally ambiguous than the air-punch-inducing Chariots of Fire, its legend was bolstered by the fact that it wasn’t released as an album for over 20 years: a rotten orchestral version, which Scott and Papathanassiou hated, came out in its absence.

Their success led to more soundtracks (although Papathanassiou was choosy about the films he worked on) and a series of 80s instrumental albums. Soil Festivities, from 1984, was the most commercially successful, but the best might be the following year’s sparse, dark and largely atonal Invisible Connections: if its contents came out tomorrow, on a limited-edition cassette released by an underground label, hip retailers such as Boomkat would be all over it.

At the other extreme, it didn’t require too much imagination to picture some numbers from 1988’s appropriately named Direct retooled as the backing tracks for hit singles. However, Papathanassiou resisted the temptation to turn his hand to pop production, his releases increasingly drifting towards new age and classical styles, punctuated by the occasional blockbusting soundtrack or event. The theme from Ridley Scott’s 1492: Conquest of Paradise gained a second lease of life as a suitably stirring accompaniment to sporting events – boxers, cricket teams and rugby league sides have all used it as intro music. He provided themes for Nasa’s Mars Odyssey mission, for the 2000 summer Olympics, wrote music to accompany the landing of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission, and scored Stephen Hawking’s memorial service, the latter music beamed by the ESA into the nearest black hole to Earth.

Then again, Papathanassiou didn’t need to dabble in rock and pop music: by the 1990s, his impact on those genres had become clear. Like Tangerine Dream’s soundtrack to Risky Business, his score for Blade Runner – finally released in 1994 – became a set text within dance music, repeatedly covered by trance artists, sampled by the Future Sound of London, Unkle, Air and drum’n’bass producer Dillinja (Boards of Canada, meanwhile, alighted on his 1976 soundtrack to French wildlife documentary La Fete Sauvage). The rest of his back catalogue was creatively plundered in hip-hop circles: by Outkast, Jay-Z, Company Flow and, again and again, by J Dilla.

In addition, Aphrodite’s Child had also been rediscovered by younger artists. If you grew up with their frontman as the kaftan-clad butt of a joke in Abigail’s Party, belatedly hearing 666 – and particularly its standout track, The Four Horsemen – was a stunning experience: who knew that Demis Roussos had once made music this experimental, this cool? The Four Horsemen earned the distinction of being effectively rewritten twice – first by the Verve on 1997’s The Rolling People, which tipped the wink to those in the know by taking its title from the lyrics of 666’s Altamont, and then by Beck on 2008’s Chemtrails – as well as being subjected to a cover version by Euro-techno titans Scooter. Elsewhere, the album’s tracks were borrowed by both Oneohtrix Point Never and Dan the Automator and, perhaps inevitably given its title and subject matter, found favour with black metal bands.

So Vangelis Papathenassiou ended up not just a garlanded soundtrack composer, the go-to guy if you needed something stirring and epic for a major event, an electronic music pioneer and the driving force behind Greece’s most influential rock band – but the thread that improbably linked Rotting Christ, Donna Summer, Boards of Canada, Jay-Z and the Verve. It wasn’t what he set out to do, but as musical legacies go, it’s a suitably unique achievement.