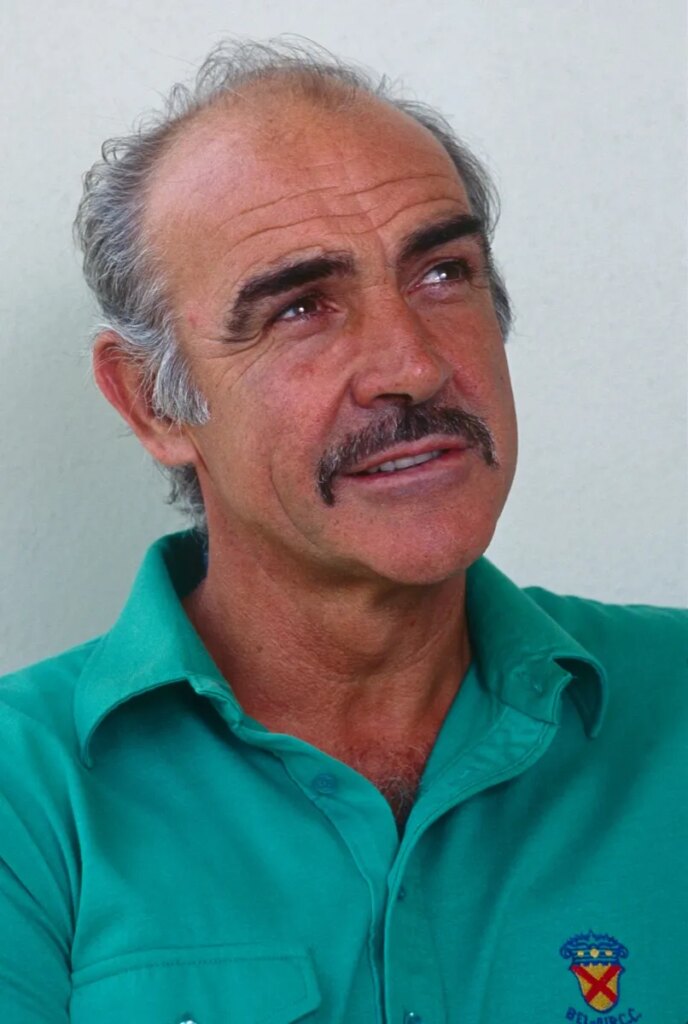

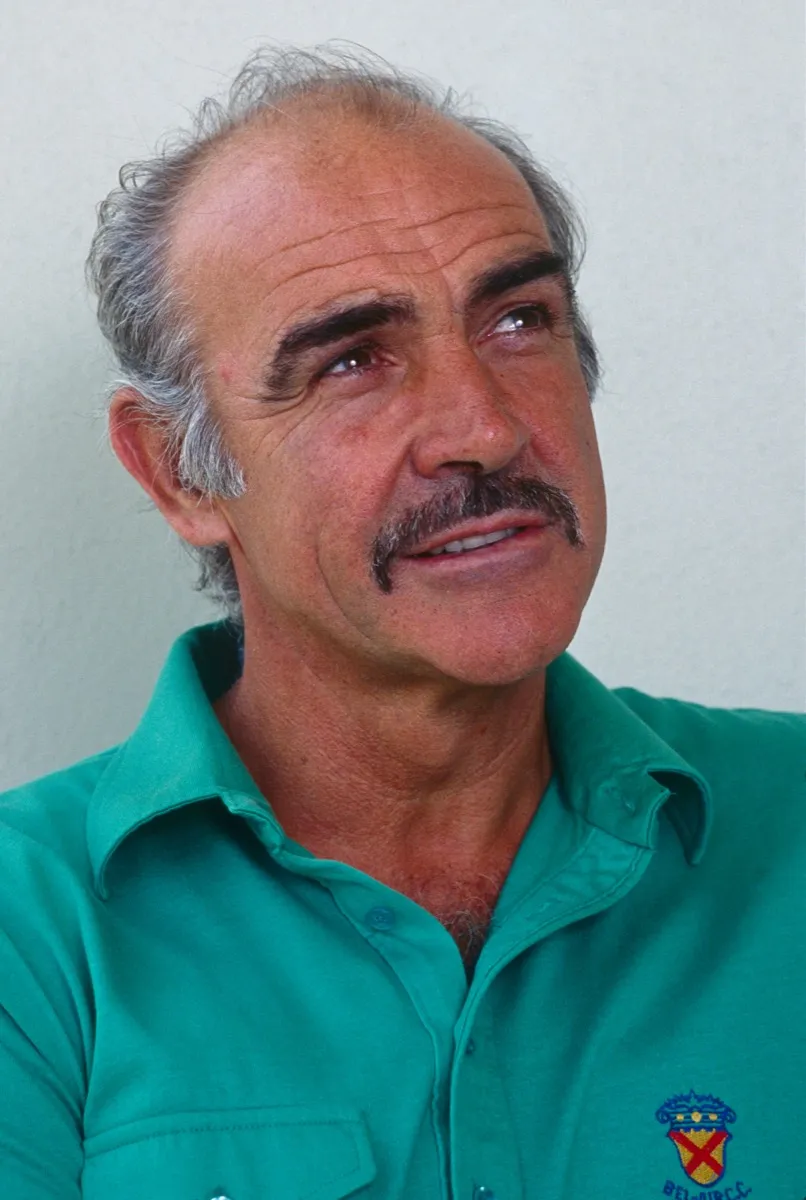

Released in 1987, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor was one of the most acclaimed films of the ’80s, taking home nine Academy Awards including Best Picture. It did so despite difficult subject matter for Western audiences—a chronicle of the troubled life of Puyi, the final emperor of China prior to the Communist Revolution—and the presence of only one well-known star, Peter O’Toole. But the producers originally sought the participation of a much bigger star for that role. Sean Connery was courted, but he turned the opportunity down outright due to the politics of Bertolucci, who he reportedly called “a commie.” Read on to find out more.

RELATED: Val Kilmer’s Director Said They Had “Physical Pushing Match” on Set of Batman Forever.

Producer Jeremy Thomas first tried to land Connery for the only role in the film to be played by a Westerner, that of Reginald Johnston, the emperor’s tutor. One of Connery’s first film roles was in 1957’s Time Lock, directed by Gerald Thomas, Jeremy’s uncle.

Thomas (the nephew) met with Connery in Rome to discuss the project, but it quickly became clear the star had no intention of taking the role. According to his recollections, as shared on the Hollywood Gold podcast, Connery was polite but insistent, saying, “I’d like to do this, but Benardo’s a commie, you know. I don’t think I can do it.”

“I had a nice conversation with him, I said ‘[Bertolucci’s] very nice, isn’t he?” Thomas said on the podcast. He said that Connery replied, “No Jeremy, I can’t [do the film].”

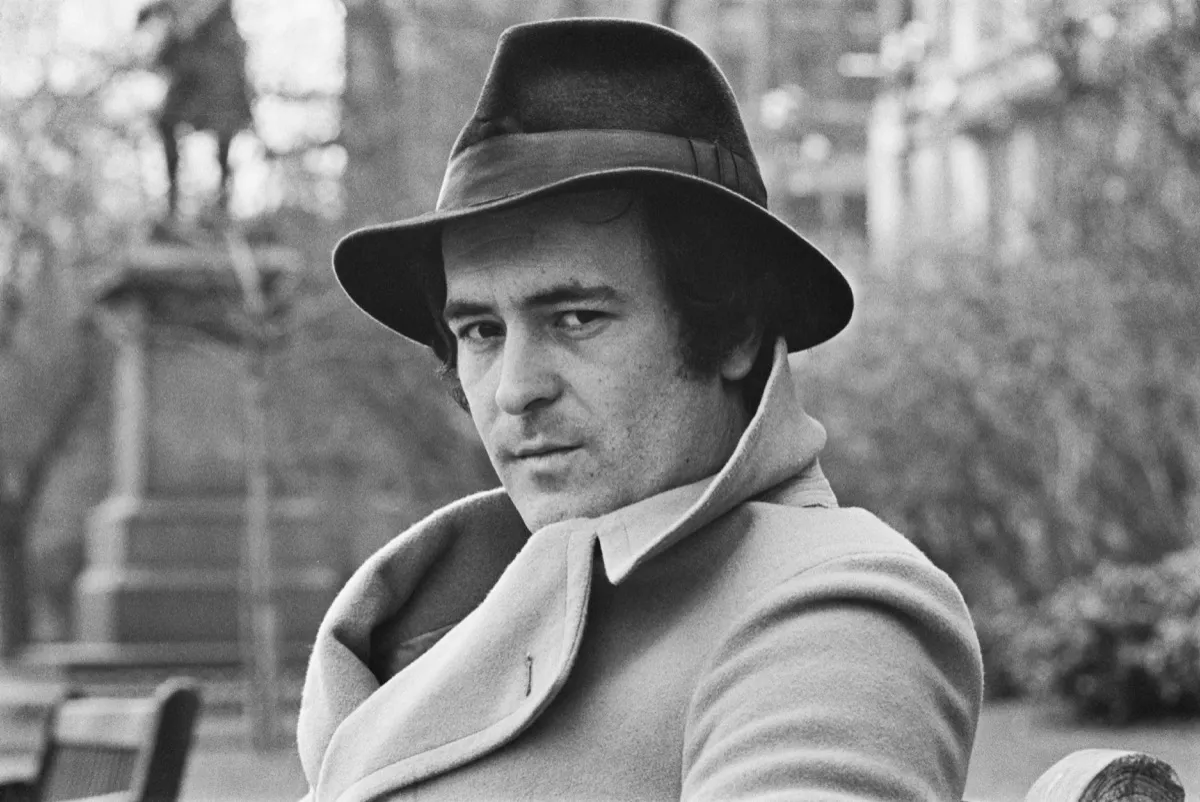

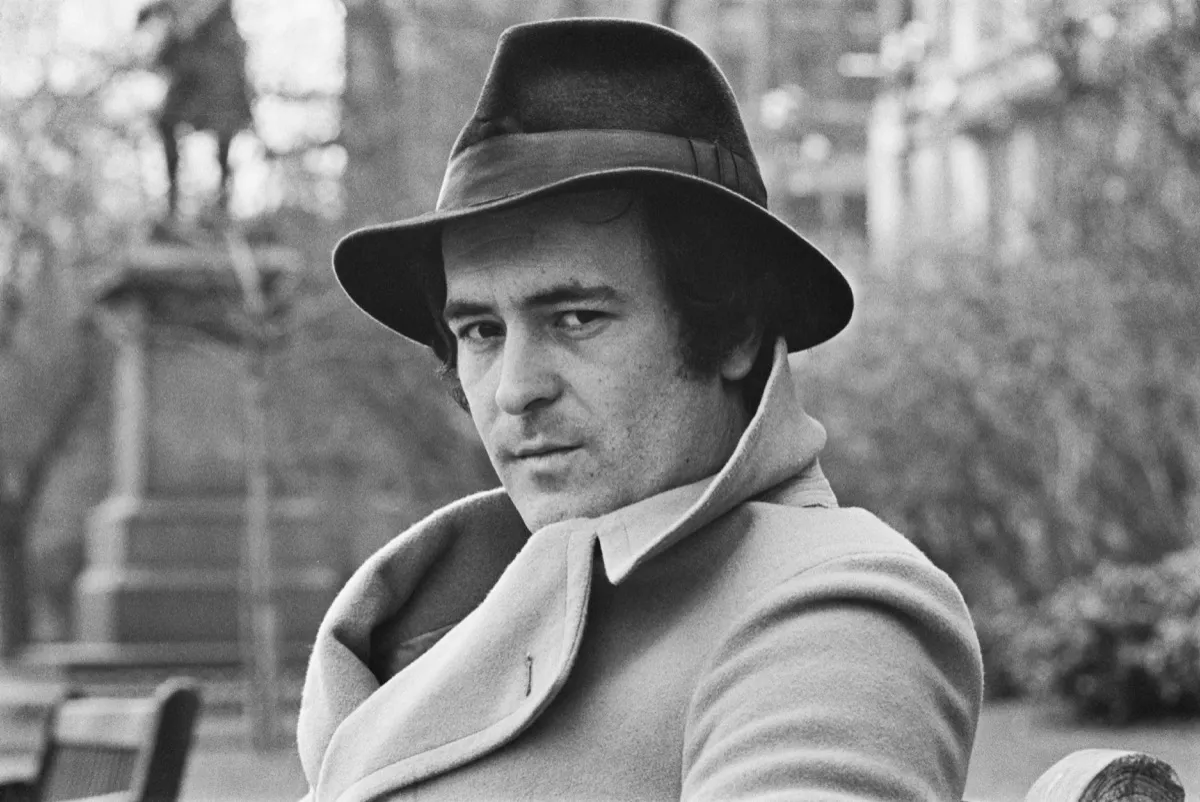

The role ended up going to O’Toole, who, according to Thomas, relished getting to visit once off-limits parts of China during filming, including the famed Forbidden City.

Connery wasn’t wrong in his assumptions about the director’s politics. The son of a poet, Bertolucci was an Italian filmmaker, and according to the World Socialist Web Site, “As much as or probably more than anywhere else…Italian filmmaking was identified with leftism, in particular with support for the Communist Party.”

Bertolucci is best known for The Conformist, a 1970 political thriller with strong anti-fascist and anti-capitalist themes; The New York Times called his sweeping historical epic 1900 “Bertolucci’s Marxist saga.”

Moreover, he was himself a member of the Italian Communist Party, and considered himself a Marxist. Speaking to the famed French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma, (as quoted by Jacobin) he once said of himself, “I was a Marxist with all the love, all the passion, and all the despair of a bourgeois who chooses Marxism.”

While the former James Bond may have been reluctant to associate with a self-proclaimed Marxist film director, Connery had leftist political affiliations of his own. He was a member of the center-left Scottish International Party, and throughout his time in the spotlight, he advocated for Scotland to become independent of the United Kingdom.

In 2000, he even accused the British government of enacting legislation barring political donations by foreign residents specifically to stop him from financially supporting Scottish independence, as he lived in Bahamas at the time, though he was still a citizen of the U.K.

Connery campaigned for the left-leaning Labor party and was critical of the conservative U.K. government. “There’s something fundamentally wrong with a system where there’s been 17 years of a Tory government and the people of Scotland have voted Socialist for 17 years,” he once said, as quoted by The National. “That hardly seems democratic.”

RELATED: Julia Roberts Was Bullied by Steel Magnolias Director: “We Hated Him,” Sally Field Says.

Connery may also have been wary of starring in a film so closely tied to the Chinese Communist Party. The Last Emperor had to walk a bit of a political tightrope throughout production. According to Thomas, as the first Western film to shoot in China, it faced “a very difficult journey” on its way to the screen.

“We had to go to China, we had to get permission,” Thomas remembered on the Hollywood Gold podcast. “Another journey back to negotiate and sign agreements with the [Communist Party], then we had to get permission to film in the Forbidden City.”

Thomas, who described the filmmakers as “all pretty lefty guys,” said they were able to find inroads in China thanks to the help of the Italian embassy there, which had, “an incredible relationship with China that helped us politically.”

Though aspects of the finished film are critical of some elements of the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese government enthusiastically supported the production, Thomas said, offering the use of the army and opening access to the Forbidden City, which had been sealed off for decades. The story of the emperor being educated in the Maoist way, post-cultural revolution did not have to submit to a censor, and the government was, in his words, “100% supportive…[They] made no commentary on anything.”