You could argue that, at least in the realm of pop music, the year 1989 belonged to Milli Vanilli.

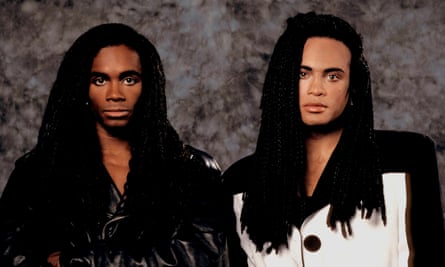

The German-French pop duo, formed barely a year earlier by the German producer Frank Farian, had already barnstormed through European charts with their first single Girl You Know It’s True. The song hit the US airwaves in March with stratospheric impact. Their debut album sold over 8m copies and spawned three No 1 singles; it stayed in the top 10 for the rest of the year. Young fans, predominantly women, screamed along to Rob Pilatus and Fabrice Morvan’s tight choreography and blatant eye candy – long braided hair extensions that swung freely when they danced, come-hither stares, chiseled abs, shoulder pads and spandex shorts, incredible energy and incredibly 80s dance moves.

“It was literally anonymity for these guys … and then superstars – the biggest pop duo in the world,” said Luke Korem, the director of a new documentary on the duo that premiered this week at the Tribeca film festival.

All of that was overshadowed, and then swept into the dustbin of pop history, by disgrace. By the time Milli Vanilli accepted the Grammy award for best new artist in February 1990, many in the music business suspected something was afoot. That November, Farian revealed in a press conference that Pilatus and Morvan never sang on any of their recordings, and lip-synced their performances. The ruse torpedoed the act – radio stations stopped playing their songs, fans destroyed their records, and the Grammys rescinded their award for the only time in history. Pilatus and Moran attempted to rebrand as “Rob and Fab” with their own vocals, but sold mere thousands of records. Milli Vanilli became cultural shorthand for hubris (Pilatus once compared the duo favorably to Elvis and the Beatles) and ignominious deceit.

And that was that. The popular narrative of Milli Vanilli – that Rob and Fab lied about their talents and misled their fans and should suffer the consequences – was swift, vindictive and enduring. And, as the documentary argues, incomplete and misdirected at the two public faces of a much larger operation. “People thought they knew the story, but they didn’t,” Morvan told the Guardian on the eve of the documentary’s premiere.

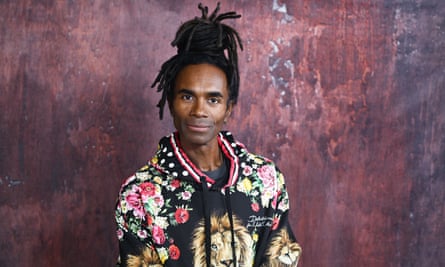

Milli Vanilli the documentary offers a brisk account of a spectacular rise and fall, primarily in the words of Morvan, a musician and artist now living with his wife and four children in Amsterdam. (Pilatus fell into drug addiction in the years following the scandal, and died of a suspected overdose in 1998, a day after leaving a rehab clinic, at the age of 32; an interview recorded about 45 days before his death provides the bulk of his story in his own words.) Raised in Paris to parents from Guadeloupe, Morvan decamped to Munich at 18, where he met Pilatus, a breakdancer, at a party. They were, as Morvan recalled, the only dark-skinned people they knew in Munich. They were great dancers and enthusiastic emcees, barely making ends meet. And they both wanted to be stars.

A brief stint as backup dancers and a shaky demo led to a meeting with Farian, a decorated producer who scored several global hits in the 1970s with the Eurodisco group Boney M. (Farian did not participate in the film.) Like Milli Vanilli after them, Boney M were a distinctly Farian, smoke and mirrors construction: frontman Bobby Farrell, a Black Aruban dancer, lip-synced over other vocals, often Farian’s, though the arrangement was met with little backlash when it became public knowledge in 1978.

Farian signed Morvan and Pilatus to a multi-album contract when they were 21 and 24 respectively. According to Morvan, the two had no understanding of the terms, let alone the possibility of lip-syncing. They needed money, and Farian was a hitmaker. “We were so naive that when the contract was put on the table,” he said. “It was never really implied, like, hey, go read that. There was no management, there was no protection. There were golden records on the wall, so that was enough.”

Months later, Farian informed Morvan and Pilatus that they would not sing on their debut single as Milli Vanilli. Morvan says they were pressured into the ruse, on pain of paying back their record contract; Ingrid Segieth, Farian’s former secretary and lover, claims they agreed easily. Either way, the track was a hit – fame and fortune at a near-viral pace – and Milli Vanilli “embraced the lie”, as Morvan recalls in the film.

Several other figures in and around the business of Milli Vanilli attest to Farian’s scheme and the music industry’s participation – if not in the plotting, then in keeping the open secret once the profits rolled in. There’s Brad Howell and Charles Shaw, the Black American singers viewed as less telegenic by Farian, who provided the real vocals on Milli Vanilli’s records and grew frustrated with the lack of credit. “Downtown” Julie Brown, who emceed for the duo on their US MTV arena tour, recalls the night in July 1989 when a malfunctioning vocal track almost derailed Milli Vanilli at the peak of their fame. Former executives at Arista, the record company which handled the duo’s business in the US, claim that everyone up to and including the company’s president, Clive Davis, knew about the lip-syncing months before the Grammys. (Davis does not appear in the film; in footage from 2017, he denied any knowledge of the lip-syncing.)

“I found it surprising when people would just run the other way still,” Korem said when I brought up Davis’s denial. After 30 years, he said, he still encountered some reticence to reveal who knew what, and when. “I think the reason they do that is because of what happened to Rob. I think there’s a lot of guilt and shame, and it’s very tragic.”

Pilatus’s death hangs over the film’s second half, as the tide turned rapidly on Milli Vanilli from phenomenon to punchline. In one remarkable scene, the pair host a press conference to address the scandal. Morvan sits near silent, shock blooming on his face in real time. Pilatus spars, both apologizing and justifying their work with Farian to escape poverty and achieve stardom. “Did you ever live in the projects?” he asks a white journalist righteous with indignation over the lie. “We had no money. We wanted to be stars.” The journalist near implores: “Your talent would get you out!” Someone off-camera remarks: “Spoken like a true white boy.”

As the music critic Hanif Abdurraqib puts it in the film, unspoken in much of the vitriol – there were over a dozen class-action lawsuits by disgruntled fans accusing the duo of fraud and racketeering – was an undercurrent of racism: “Milli Vanilli, to be clear, had a largely white audience. So a part of the betrayal that was felt was, ‘I can’t believe I listened to these Black guys singing these songs and it really wasn’t them.’”

The issue, as the film frames it, was not that Morvan and Pilatus had culpability, but that they shouldered the entire scandal alone. “Do they deserve to be called out on some level? Sure. But what about everybody else?” said Korem. Farian, Arista, their record executives and their management emerged largely unscathed.

“It’s mind-blowing to think that the media just went after us, and never went after the people pulling the reins,” said Morvan. “It’s almost as if they said, ‘Hey, listen, we can’t touch the man in black, so that energy should go toward [Rob and Fab].’”

Three decades on, Morvan sees the Milli Vanilli saga as a re-embraced chapter, and the film as “a story of hope. You can fall, but you can also stand back up, reinvent yourself and go.” The film ends with a solo rendition of the group’s biggest hit, Blame It on the Rain – Morvan singing in his own voice, at his own concert, to a crowd happy to hear music they once loved.