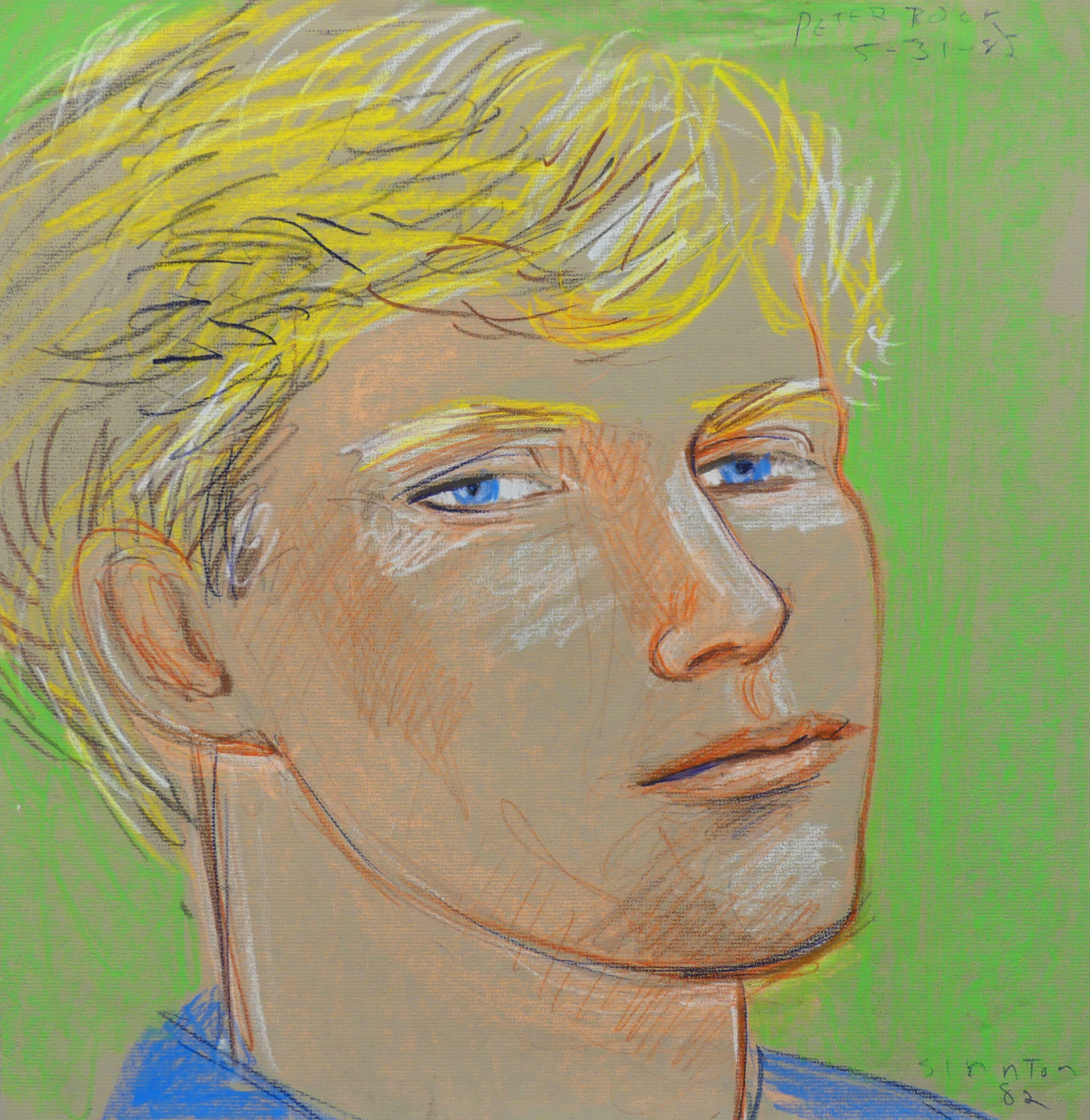

In 2018, the Italian theater director Fabio Cherstich visited the Greenwich Village home of Arthur Lambert to see Lambert’s collection of works by the artist Larry Stanton. Stanton, Lambert’s lover, produced a significant body of work—mostly drawings and paintings—in the four years leading up to his death from AIDS-related complications. Stanton drew portraits of the young men he slept with, as well as his friends and family. Many of Stanton’s subjects were other gay men who died in the 80s from AIDS, and his brightly colored faces sketched quickly in crayon and colored pencil stand as an archive of lives lost.

Lambert inherited all of Stanton’s work after he died. Since meeting Cherstich, the two have founded the Estate of Larry Stanton to bring renewed attention to Stanton’s art. A collection is currently on display at Daniel Cooney Gallery, while Acne Studios has presented an exhibition of works and objects featuring Stanton’s drawings in Milan, Seoul, and Tokyo, with a New York exhibit showing from February 9. Lambert and Cherstich met over Zoom to discuss Stanton’s life and legacy, and the work they’re doing together to bring recognition to Stanton’s art.

———

RENNIE McDOUGALL Since I have the both of you together, I thought we could start with how the two of you met and how you’ve built your relationship around Larry’s work.

FABIO CHERSTICH: Everything happened because I contacted Arthur through his website. I was doing research online on the work of another artist which I love and collect. His name is Patrick Angus. Patrick Angus made a beautiful portrait of Arthur Lambert and that’s how I found out about Larry Stanton. I was looking online to understand if someone who was portrayed by Patrick Angus was still alive and it was possible for me to be in contact with [them]. I sent an email to this Arthur Lambert, tried to understand if he was the person who was the subject of the portrait, and he answered me. He said, “You should come to New York and visit me because I have many works of another amazing artist,” so it was a very nice coincidence. As soon as it was possible for me, I went to New York and visited Arthur and he showed me all of Larry Stanton’s works, and he started to tell me his story. I fell in love with the work. And I fell in love with Arthur also. He’s an amazing person. He’s a real New Yorker. That’s how everything started.

ARTHUR LAMBERT: When Larry died, he had just sold seven works. I inherited everything. He only really painted for four years. He had a nervous breakdown around 1979 or 1980, and when he got out of the hospital, he just painted. It was all he did. His kids [subjects] were escaping their hometowns, escaping their parents, they wanted a real life. And it’s amazing, he was able to get so many of them. I don’t know how he got all those kids to sit.

McDOUGALL: I want to hear more about his work but I thought it would be good to jump back to when you first met Larry in 1967 on Fire Island. I know you also later owned a house there. How important was that environment for gay men in the 60s and 70s? And how important was it for Larry and his work?

LAMBERT: Well, when I met him in 1967, I’d already heard about him—the gay community was small in those days—and he was so attractive that when he came to New York, the word about him was everywhere. I wanted to meet him, too. We were sitting at a restaurant overlooking the boardwalk [on Fire Island] and when he appeared I just ran out of the restaurant. He said I looked so nervous. I was shifting back and forth. I had a little rental and I said, “Why don’t you sleep on the couch?” So, he did. Basically that’s how the relationship started. But Fire Island didn’t have much impact on his work, I don’t think.

CHERSTICH: There are some beautiful photos that he took, and Super 8 movies. In a way, I think that even if it was not the main work of Larry’s, he was doing it like a hobby because it was normal for people to have documentation. Now we have the iPhone, but at the time, Super 8 and photo cameras gave the possibility of recording time. The amazing thing is that the way he was shooting the video images was with the eye of an artist. You have these beautiful images of gay men and their time together in Fire Island. Of course, he was someone living so close to David Hockney that you could really feel the influence the territory had on him, like on many other artists from his generation. But he was lucky enough to live with him, to have him as a friend.

LAMBERT: Those summers we had! We had a lot of interesting people come through. I mean, Henry Geldzahler and David Hockney spent two summers there. We had Robert Mapplethorpe. We had Paul Newman’s son, who was gay. We had John Paul Getty, the one who had his ear cut off. All these people came through.

McDOUGALL: And it’s such a big part of his work, meeting people and capturing them. I’m curious about his interest in figurative work and portraiture and his relationship to both when it was maybe less fashionable. What drew him to that? Were there any other artists doing figurative work at the time that he really admired?

LAMBERT: Well, there weren’t many doing figurative work and that was a problem for him because he so wanted to be recognized. It was all abstract expressionism. Henry Geldzahler had a show at the Met in 1970, [New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970] the first show that ever had contemporary artwork [at the Met]. It was 36 galleries, a really big show. Larry spent every day there. He met all the artists. But it was a problem because they were all abstract expressionists, and it was not what he was drawn to. He had to draw what he felt emotionally and that was portraits of his family, kids, anyone. It was difficult for him because he didn’t know if he’d ever get accepted. That’s why he said to me, when he was dying, “Please try to make my work better known.”

CHERSTICH: Patrick Angus had the same problem when he was alive. There is a documentary about Quentin Crisp where you see the real Patrick Angus with Quentin Crisp visiting a gallery and you listen to this gallerist telling him, “next, next, next.” And Patrick was showing these beautiful paintings about the strip clubs in New York, which are masterpieces, but they were not good for the market. Not in the right trend. And they were too gay. They rejected him because of AIDS. There was this stigma. Thank God we now have the possibility to show this work and people can understand, but it’s too late. It’s never too late to remember, but now there is a responsibility from people that were leaving these people behind during that time. They were not accepting, not able to understand. It is about the art system, the art market. The story of Larry is the story of a lot of other artists.

McDOUGALL: I found all his works with colored pencil and crayon particularly beautiful and striking. Is there something that drew him to the speed of those mediums? You mentioned the difficulty of having sitters sit for a long time.

LAMBERT: Yeah, he could get the kids to sit for long enough that he could draw them. He couldn’t paint them. Painting came later, and the paintings weren’t from life, but the drawings are from him sitting right in front of you. I got a call the other day from Los Angeles from somebody that we knew in 1968. He found the book and he’d spent days searching trying to get in touch with me and he called me yesterday. Pretty amazing.

McDOUGALL: His use of color made me think of Hockney’s influence.

LAMBERT: Well, he was so in awe of David Hockney. He painted David. It was beautiful, one of his best paintings, but he didn’t feel that it lived up to David’s expectations, so he destroyed it. He was crazy about David and crazy about his work.

McDOUGALL: There was also something you wrote in the book, which I thought was very beautiful, that because of a lot of his subjects were young men, they didn’t have the time or the life experience for character to develop in their faces. Do you see an added poignancy in the work because so many of these men, including Larry, died in the 80s of AIDS?

LAMBERT: Oh yes. The only indication that they ever passed through life are his drawings. These kids have a bit of a legacy, even though they didn’t have a life.

CHERSTICH: I always ask myself, “What if he didn’t die? What if he had the possibility to go on with his research doing paintings? What kind of level could be reachable for him if the start was so good?” That’s the problem with this generation of artists. They died too young. The history of art has a huge gap because of a generation of artists who unfortunately died too young. Imagine if Hockney died when he was 37, or if Alex Katz died when he was 35. It’s quite impressive what Larry was able to create in four years. Very intense, because he was constantly drawing.

McDOUGALL: What do you remember of Larry’s feelings at the time, and of how he approached his work in the last years of his life?

LAMBERT: He was absolutely obsessed with his work and carried a sketchbook everywhere. And when he had a coffee, he’d sketch the people in the coffee shop. He was completely committed, that’s really all he did other than take boys home, for a dual purpose. In the hospital, that’s the way he retained himself. He drew. The nurses would say, “Doesn’t he know he’s dying?” Well, he didn’t want to go there. I didn’t want to admit it. Eventually, they forced him to be intubated and he didn’t want to be intubated. He kept pulling out all the tubes, so they tied his arms to the bed. At that point, he couldn’t draw anymore. He couldn’t scratch himself. He was tired. It was really a disgrace.

CHERSTICH: At the end, when he was in the hospital, he made these beautiful drawings which Arthur used to call the “death drawings,” but I prefer to call them the “hospital drawings.” And these works are so beautiful, so full of pain and joy. All these works, the portrait that he made of Arthur crying, and this black and white portrait of a table with someone who’s just bringing in some flowers. It’s so simple, and so relevant. Every time that I look at the drawings I’m so touched. I have this strange feeling of a friend coming from the past that I never met, but of course after so many projects and books and exhibitions and constantly listening to the story, I discovered something. I met him through his work. There’s also something very important about Arthur’s generosity in sharing Larry’s work because it’s telling the community that if we are close to each other, if we support each other—especially in the 80s where the family, for a lot of gay men, was a catastrophe. And this idea of a new family, which was not the mother and the father, but the community, the boyfriend, the friends—these are heroes. It speaks a lot to me for my generation. [But] it’s such an example on how it’s possible to fight, how it’s possible to support, how it’s important to remember and to preserve.

McDOUGALL: It’s heartbreaking to hear those words that he shared with you about making sure that his work was recognized. What has it been like to now bring that to fruition?

LAMBERT: Very fulfilling, of course. I’m thrilled because I thought his work was terrific. I had him on my wall for 35 years. I never got tired of it. Henry said that’s the sign of good art, if you don’t get tired of it, it keeps giving you something.