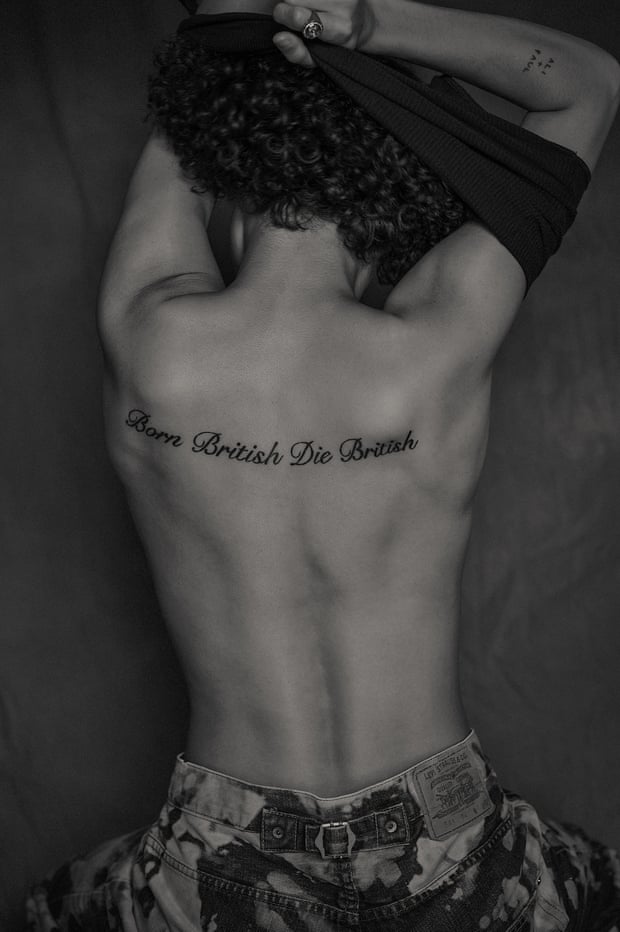

Two years ago, the young artist Rene Matić had the far-right slogan “Born British Die British” tattooed on their back. The words unfurl in a delicate font across their rippling shoulders in the elegiac black-and-white portrait they then commissioned from one of their heroes: the celebrated street photographer Derek Ridgers. His early work with 1970s and 80s skinheads captured a burly tribal energy often fuelled by extremist views. Inked on a Black lesbian body, the phrase becomes a lot more than a war cry for embattled white men. “[The tattoo] was always about the in-between moments of being born British and dying British,” Matić says. “That’s what my story is all about.”

For the artist, skinhead culture’s roots, when white and British Jamaican kids danced side by side to ska and reggae, and the movement’s later infamous tilt to the far right, make it “the perfect metaphor for talking about West Indian and white working-class culture – my culture”. Skinhead insignia is a leitmotif throughout Upon This Rock, the 25-year-old’s first big solo show of their film, photography and sculpture, at the South London Gallery. So, too, are crosses and flags, the major emblems of nationhood and church.

Yet it is how everyday people reach for, use and at times overturn these limited symbols that are one of the exhibition’s core themes. It is an ethos summed up in the title of Matić’s 35mm photography series, flags for countries that don’t exist but bodies that do, an ongoing document of their life in which identity shifts constantly – from their wife Maggie’s fabulous outfits to their nephew Rudi’s childhood passions.

The star of the show though, is the artist’s father Paul, whose raw, troubled life is handled with a gossamer touch in Matić’s astonishing first film, Many Rivers. Paul is, improbably enough, a Black skinhead, who, inspired by an older white stepbrother, first found a sense of belonging and release with local skins in his home town of Peterborough. This, however, is far from the most extraordinary thing about Paul. His lifelong struggle with identity has knotty roots, beginning with the institutional prejudice that divided his father from the white Catholic mother he never knew. Childhood abuse, care homes, alcoholism and the pervasive shortfall of possibility in a failed “new town” have all taken their toll. “My whole life with my dad has been tortured by the ambiguity of his past,” Matić says. “I set out, not necessarily to tell his story, but learn it for both of us.”

Explored through family members’ often painful recollections and footage of Peterborough’s forgotten housing developments and broken-down churches, the film could have made grim viewing. Instead, it’s as ebullient as it is moving, shot through with moments of freedom, laughter and caring: Paul dancing jubilantly in an otherwise drab backstreet and clearly loving the camera; his sister’s solidarity; his sheer charm as a storyteller. As the artist points out, “the crux is a working-class diaspora’s survival and triumph”.

A sculptural installation riffing on the symbol of the crucified skinhead with bronze Christs inspired by Paul, affirms him as a victim with the potential for salvation and resurrection. “When Paul talks about being a skinhead in the film, his face lights up for the first time: suddenly, he has a purpose,” Matić says. “This story is about the cause and effect of pain and suffering, and what, if anything, saves us in the end.”

Three more works …

Destination/Departure, 2020

“This was partly inspired by earlier photographs of fascist tattoos Derek Ridgers had taken,” says Matić. “I wanted to insert myself into that narrative. I came across Derek’s photos [of skinheads] when I was younger. I think I was searching for myself, or my dad, in that scene. His work was instrumental in me understanding my culture, identity and position – and opposition.”

Maggie in Orange, 2021

“This is one of many photos of my wife, Maggie, and their ever-changing hair, which acts as a marker of queer time in this series. The exhibition explores how faith has presented itself to me and the people I love. Here, the way Maggie is represented is reminiscent of a kind of holy spirit. My gaze is that of pure love and belief.”

VE Day Skegness III, 2020

“This was taken during the 2020 lockdown when Skeggy came out in full patriotic force. I had been isolating there with my wife and hadn’t seen another person of colour for three months and was feeling the weight of it. It felt like a dystopia, like some Get Out shit. One day, I’d been accused of stealing a parcel I was carrying. I stole some flags – which were everywhere – instead. This is me, understanding that gaze.”

Rene Matić: Upon This Rock is at South London Gallery until 27 November.