Was Andy Warhol the first influencer of the modern world? The artist may have died two decades before social media turned the word into a job title, but Warhol’s prolific use of photography to capture a carefully curated life would have won the artist millions of followers today.

The artist as influencer is one of the themes the Art Gallery of South Australia will explore during the 2023 Adelaide festival in March, in Andy Warhol & Photography: A Social Media. It will be the first exhibition in Australia to focus on the artist’s lifelong obsession with photography, sourcing works both by him and of him from more than 30 public and private collections from around the world.

More than 250 works, including experimental films, silkscreens and paintings, will join the AGSA’s own extensive collection of 45 Warhol pieces, with the central photography component promising a candid glimpse into the pop artist’s celebrity-studded New Yorker lifestyle.

The AGSA curator Julie Robinson told Guardian Australia the exhibition will go a long way in demonstrating just why the artist, some 35 years after his death, remains as relevant and collectable as ever. Earlier this year his Shot Sage Blue Marilyn became the most expensive piece of 20th-century art ever sold at auction, with the US$195m price eclipsing the previous record set by Pablo Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger (Version 0), which sold for US$179.4m in 2015.

“We’re all very familiar with his pop art paintings and sculptures but looking at his very public works, you don’t really get much of a sense of him as a person,” Robinson says of Warhol, who famously described himself as a “deeply superficial” human being.

“So in looking at these photographs, you find out much more about Andy Warhol as a person. He was an extraordinary person, but he could also be an extraordinarily ordinary person as well.”

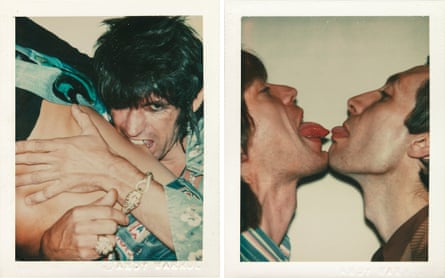

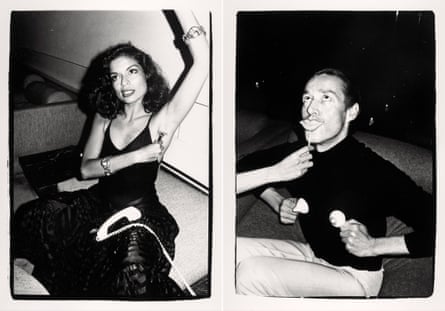

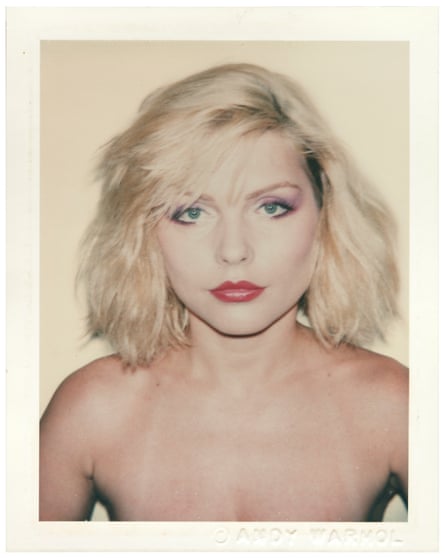

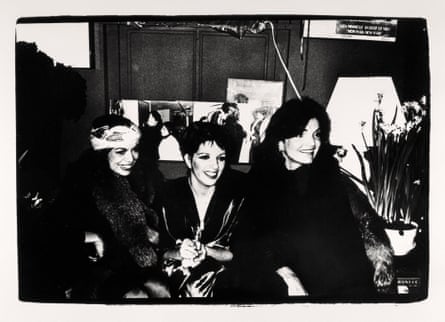

Like many of his iconic silkscreens, Warhol’s photography is drenched with celebrity presence. But the glamour is surprisingly lacking in many of the images.

Warhol once said a good photograph is of someone famous doing something unfamous. So think Bianca Jagger shaving her armpit, or a bleary-eyed Mick Jagger at table with Warhol and William Burroughs, regarding the food before them with grim disinterest.

Muhammad Ali, Bob Dylan, Debbie Harry, John Lennon, Liza Minnelli, Lou Reed, Elizabeth Taylor – the superstars of the 60s, 70s and 80s all gravitated to Warhol’s infamous Factory in midtown Manhattan, and a camera was always at the ready.

And for the last decade of the artist’s life, an Australian was at the heart of it all. In the mid to late 1980s, Henry Gillespie was the editor of Warhol’s Interview magazine: the publication the artist co-founded in 1969 and which continues to occupy an uber-cool niche of celebrity art and culture reportage.

Gillespie, who grew up in the Riverina town of Deniliquin, met Warhol in Manhattan in 1979 at the opening of the artist’s Portraits of the 70s exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

“That was a crucial turning point in Warhol’s career because, for the first time, people started to consider him a serious artist,” says Gillespie, who believes his status as an Aussie in New York held particular fascination for Warhol.

“‘Oh, an Australian’, he said when we were introduced, and then he drew back a bit and gave a sort of a gasp and said, ‘I’ve heard it takes 30 days to fly there’.”

Gillespie remarked that 30 days flying was more likely to get him to the moon, and soon the Australian was a regular fixture at the Factory.

“Australia held a fascination for him. He liked the concept, which he couldn’t quite comprehend, of the great distances and the flatness, all the beautiful beaches and the beautiful people,” Gillespie recalls.

“This was a time in New York when the Australian government was doing the ‘put another shrimp on the barbie’ tourism campaign … it made everything look very appealing and that fascinated him. To be an Australian then had real cache; I think he saw me as something of an exotic.”

Warhol became intrigued with Australian convicts and Australian lifesavers. At one point he asked Gillespie if he could procure some mugshots of criminals down under.

At the time of the artist’s unexpected death (Warhol died in 1987 at the age of 58 from surgery complications), Gillespie and the Australian philanthropic team of Victor and Loti Smorgon were in the process of arranging a visit by Warhol to Australia.

Gillespie and Loti Smorgon are the only two Australians Warhol ever painted.

Four Warhol portraits of Gillespie now reside in Australia: one in the AGSA and three in the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

Gillespie says he feels deeply honoured that he got four, from an artist he was fortunate enough to call a friend.

That “deeply superficial” persona may have been what Warhol wanted the public to believe, says Gillespie. “But that’s not who he really was. That was contrived … and behind it was incredible discipline and hard work. He was part of the firmament of New York.”

Had Warhol survived into the 21st century, Gillespie is confident the artist would have been in his element in the world of social influencers.

“He would be a 94-year-old on a Zimmer frame with a smartphone, and he would have absolutely lapped it all up. He would have loved the era we’re living in now.”