In an industry teeming with publicity-hungry executives, the late Frank Biondi stood apart. An architect of modern-day Hollywood, he quietly shaped media companies into creative powerhouses.

Biondi led HBO in its early years. He helped build Nickelodeon and Comedy Central into iconic brands. He provided critical seed money to a nascent production firm that went on to make “When Harry Met Sally” and “Seinfeld.” He saw value in turning a single show, “Law & Order,” into a multi-series franchise. And he was a guiding force in the formation of the Tennis Channel.

His youngest daughter, Jane Biondi Munna, long felt that few people recognized his many contributions. For years, she would nudge him: “When are you going to write your book?”

“He would laugh and say: ‘I’ll do it when Sumner dies,’ ” Biondi Munna recalled in a recent interview.

His response hinted at the complexities, and perhaps a lingering sting, from a roller-coaster Hollywood career. Biondi was famously fired by the combative Sumner Redstone, Viacom’s longtime chairman, in 1996 — just as the company was hitting its stride.

Biondi’s unceremonious departure from Viacom is one of many memorable tales included in his memoir, which was self-published last month by his family after he died. The story of how the book came to be is a remarkable testament to a daughter’s determination to make sure her father’s legacy was honored — and remembered.

Biondi was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2018, when he was 73. When Frank and his wife, Carol, called from Los Angeles to share the diagnosis, Biondi Munna recalled saying, through tears, “Well, Dad, now you really have to write this book.”

He’d had the same thought. A week or so earlier, Biondi had emailed his daughter — a JP Morgan Chase executive who lives in New York City — a list of building blocks for the book: experiences from his career and business lessons.

“The next time I was with him, I whipped out my iPad” and began recording, Biondi Munna said. “I didn’t want to waste another minute.”

Thus began a year of reflections and recordings. The project also deepened a bond between father and daughter.

“In his last year, I learned more about my dad’s life before me and my sister were around — more than I’d ever known,” Biondi Munna said. “I learned about his early jobs, things that shook his confidence and how he thought through certain challenges.”

They had completed recording 40 of his stories when Biondi, then 74, died in November 2019.

While delivering the eulogy at her father’s memorial service, Biondi Munna vowed that she would make sure his book would be finished.

But there were obstacles. Not a single chapter had been written when he died. The publishing house that had expressed interest in the project withdrew. And Biondi Munna and co-writer Jeff Wilser struggled to find a format to present the material without it turning into a “how-to” book on executive leadership, something that her father had said he didn’t want to write.

“After he died, we were left with the individual pieces — parts of a book — but it was not a book,” she said. “So it was like fitting the puzzle pieces together.”

She was desperate to preserve his words — his voice — in his own story.

“We had done so much work. And he had related all of these stories — in the toughest year of his life,” she said. “I felt that I had to finish it.”

Biondi’s friends stepped up. To fill in the gaps, high-powered associates — including former MTV chief Tom Freston, former Walt Disney Studios and former Warner Bros. film chief Alan Horn, former Paramount Pictures Chairwoman Sherry Lansing, Tennis Channel President Ken Solomon and former Fox President Peter Chernin — provided their own remembrances about working with Biondi.

TV personality Dr. Phil McGraw (a friend and frequent tennis partner) contributed his recollections of Biondi’s take on life.

Biondi Munna reluctantly began writing her own memories, serving as the book’s narrator, to bridge everyone’s stories.

Writing became her pandemic project, and a labor of love. Last month, the Biondi family self-published “Let’s Be Frank: A Daughter’s Tribute to her Father, the Media Mogul You’ve Never Heard Of,” distributed by River Grove Books.

The 212-page paperback contains Biondi’s insights about how the movie and television business evolved from the 1970s into the early aughts. He started as an investment banker before segueing into cable television. He joined Time Inc.’s Home Box Office in 1978, and became its CEO five years later.

In the mid-’80s, after Coca-Cola made its Hollywood entrance by buying Columbia Pictures, it hired Biondi to run its entertainment division. While there, he assembled an enviable portfolio by acquiring Merv Griffin Enterprises (with rights to “Jeopardy!” and “Wheel of Fortune”) and Embassy Entertainment (Norman Lear’s company). Biondi also agreed to invest in Castle Rock Entertainment, which then made Rob Reiner movies and “Seinfeld.”

Coke sold the business (after Biondi left) to Sony Corp., which continues to reap huge dividends from his 1980s deals.

Much of Biondi’s career spanned “the era of the media mogul — Steve Ross, Ted Turner, Rupert Murdoch, Sumner Redstone, Michael Eisner and others,” Alan Schwartz, executive chairman of investment firm Guggenheim Partners, said in an interview.

“Back then, the media business was heavily a deal-making business,” Schwartz said, adding that, four decades ago, Biondi helped him navigate a business full of big personalities. Schwartz’s reflections also are contained in the book. “This was an industry with a lot of battles between individuals who always wanted to win,” he said.

In the heat of battle, Biondi revealed his deft touch.

“Frank never tried to win: He tried to get himself a good deal, but he wanted the other guy to walk away with a good deal also,” Schwartz said. “So people wanted to deal with him.”

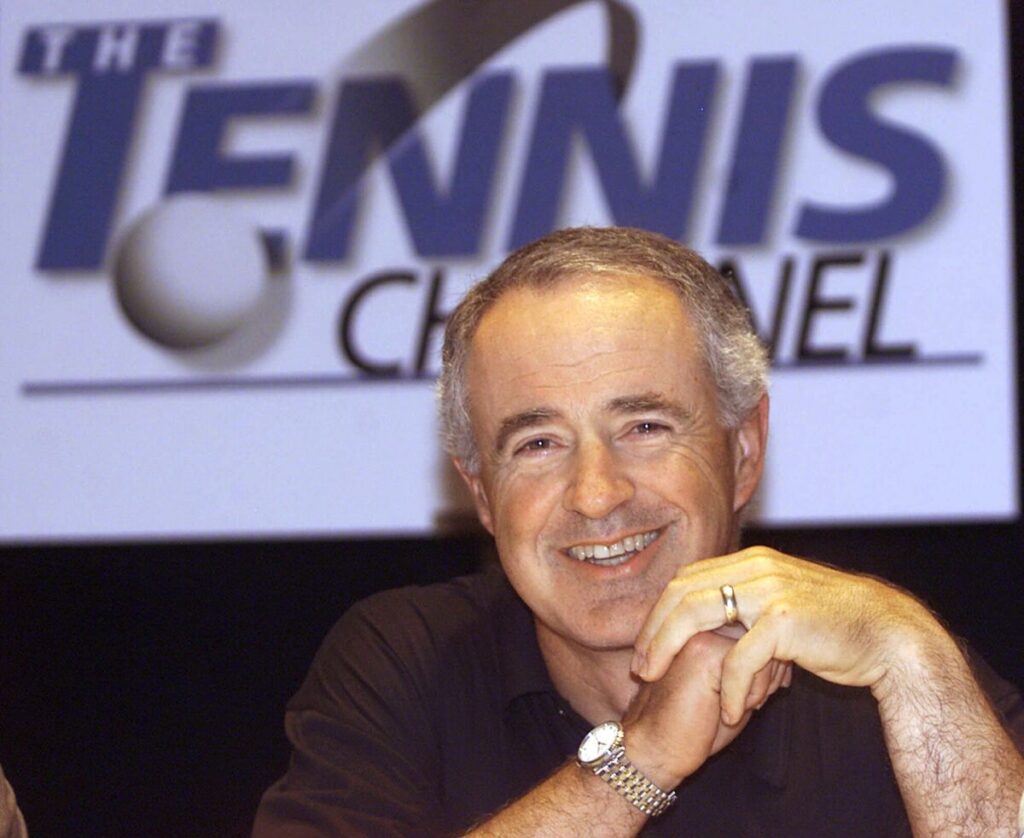

Frank Biondi, former CEO of Viacom, smiles as he takes questions during a news conference announcing a new cable network, the Tennis Channel, in 2001.

(Beth A. Keiser / Associated Press)

When Redstone acquired Viacom in 1987, he hired Biondi as CEO. They achieved much success, but one episode altered the dynamic.

Respected media writer Ken Auletta profiled Biondi for a 1995 New Yorker magazine article, “Redstone’s Secret Weapon.” In the first paragraph, Auletta wrote, “Viacom chairman Sumner Redstone is the one who bought Viacom, but Biondi is the one who has built it.”

That infuriated Redstone, and within a year, Biondi was bounced.

“He came into my office and closed the door, which was atypical,” Biondi wrote, adding that Redstone then told him: “Look, it’s been terrific working together but I’ve made my mind up. It’s time for you to move on.”

Biondi said he challenged Redstone, saying the business was starting to hum. Redstone replied: “Quite honestly, I’m tired of sharing the credit.” (Redstone then became CEO.)

Neither Biondi nor his daughter took swipes at the Viacom mogul, who died two years ago — nine months after Biondi’s death.

But Biondi did calculate what Viacom’s market value might have been had Redstone held onto Viacom’s original assets and not chased so many headline-grabbing deals — a bid for Paramount Pictures, which nearly sunk the company, then acquiring CBS (then spinning it off, then merging it with Viacom again). That chapter is called “Sumner Redstone Could Have Been (Really, Really) Rich.”

The book shares lessons in finance, management, the value of hard work and treating people with respect.

Former Microsoft executive Blair Westlake, who worked with him at Universal Studios, described Biondi as possessing a “Jimmy Stewart-like” talent to make difficult endeavors, such as running a media company, “look easy.”

“He possessed the skills and characteristics of few executives: Secure, focused, unflappable, sense of humor, empathetic,” Westlake said. “Everyone I’ve met who reported to Frank at some point have described him as the ‘best boss in their career.’ ”

Schwartz said Biondi remained grounded because “Frank never allowed himself to be intoxicated by the media business. He didn’t need the limelight.” That, and, because his greatest love was his wife and their two daughters.

“As outstanding as he was an executive, he was even more outstanding as a friend and as a family man,” Schwartz said.

Biondi Munna acknowledges that, had her father lived longer, they could have written a more complete “window into the world that he lived.” But she was inspired to keep going during the pandemic, “because I kept thinking about how much the world needed to be reminded of a different type of leadership than what we’ve seen in the world and in politics.”

“He was everything you don’t hear a lot about: Kindness, stability, thoughtfulness and hard work,” she said. “There is real value in substance — both in the substance of your work and in the substance of your character.”