I confess I am a philistine when it comes to classical music. It’s not that I don’t like it – I went through a period as a teenager in Southend when I drove around with Classic FM blaring out of the speakers of my battered Fiat Uno. But even this, to tell the truth, was mostly in performative contrast to the music that pumped out of the souped-up cars of the local wideboys. Occasionally, when I particularly enjoyed a piece, I would listen out for the name of the composer. It was usually Vaughan Williams. That’s as far as my self-education went.

It is rather shaming to realise that I have never bothered to do more than scratch the surface. In those teenage years, my musical preference was largely for pained, romantic singer-songwriters like Jeff Buckley. I would listen to The Last Goodbye, deeply relating as he sang “This is our last embrace / Must I dream and always see your face?”, despite having never had a relationship that lasted more than three months.I suppose I got my fix of orchestral music in the arrangements of artists such as Björk and Nick Drake, or film composers such as John Williams, whose work was etched into my brain like any other child of the 80s.

So when Aurora Orchestra’s Nick Collon and Jane Mitchell got in touch to ask if I would like to be involved in Aurora’s 2019 Prom performance of Symphonie Fantastique by Hector Berlioz, I had a split-second decision to make. Do I pretend I know who the hell Berlioz is and claim to be a huge fan of the piece, or do I confess my total ignorance? Luckily, Collon began to explain before I even made my decision. I suspect he knew. His eyes lit up as he told me it was his favourite symphony and explained the story behind its composition.

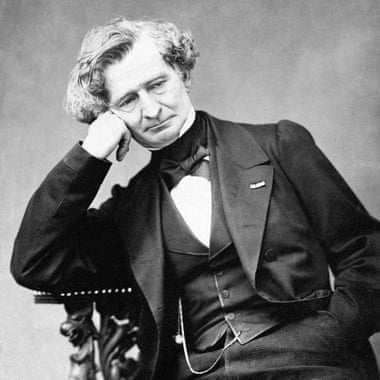

Berlioz was a young composer living in Paris in 1827 when he went to see an English theatre company performing Hamlet at the Théâtre de l’Odéon. He was instantly smitten with Harriet Smithson, the actor playing Ophelia. He became obsessed, watching her come and go from her apartment, which happened to be opposite his own. He wrote her passionate letters to which she did not reply. He found himself tortured by this unrequited love, depressed, unable to sleep. After two years, he decided he would write a symphony so brilliant, it would “stagger the world” and Harriet would be so impressed that she would surely love him back.

The symphony he wrote was one of the first attempts to tell a story through music. As Collon put it to me, a film score before there were films to score. Berlioz did not stray far for inspiration for the narrative, telling the story of an artist who sees a woman and falls desperately in love with her. The thrill of this love sours into a torturous isolation and, believing his love to be unrequited, the artist poisons himself with opium. He slips into a terrible dream in which he kills his love and is subsequently executed for her murder, whereupon he is surrounded by witches and demons who dance and celebrate his death.

His Symphonie Fantastique did indeed stagger the world: Smithson eventually heard it and, remarkably, they got married. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the relationship was not built to last. Within years, Berlioz began an affair with a new infatuation.

Ghosts was yet to air when we first worked on this concert, but I chuckled at the more than passing resemblance to the melodramatic late poet Thomas Thorne, who I play in that show, a character driven by an obsessive infatuation with somebody he barely knows, and whose mood is constantly swinging between states of ecstatic mania and agonised melancholy. Whereas the poetry this inspires in Thomas is terrible, in Berlioz, it inspired a masterpiece. His Symphonie Fantastique is truly a groundbreaking work of genius. The idée fixe is the major innovation Berlioz made – a short melody we associate with the object of the artist’s affection. It appears when he first sees her and recurs whenever he encounters her (or the thought of her) again, recognisable but changed each time depending on the context in the story, just as we might recognise in the character themes of a film score such as Star Wars, recorded around 150 years later.

Berlioz wanted his description of the symphony’s narrative to be included in the programme at any concert where it was performed. Aurora’s plan was to go one step further and do something theatrical with a staging of the piece. We didn’t want to pantomime the story through each movement and thereby diminish the power of the music, but rather to open it out somehow and introduce a little of Berlioz’s character. We used the composer’s own words to explain his motivation for writing the symphony and to prompt each movement of the piece.

I love the way Berlioz described the depths of his feelings and the heights of his ambition. It is easy to find him a little ridiculous, and it is clear that his feelings for Harriet are obsessive and superficial and do not seem to extend to wanting to know her fully as a human being. But anyone who has ever been young and lovesick will know how horribly consuming it is when you are going through it. And I am sure that many people, like the young me, will have found that the greatest balm can be the work of an artist who has found a way to vividly describe that feeling back to you and, in so doing, make you feel less alone.