A pivotal moment in the career of the British drummer and percussionist Tony Oxley came when a successful European tour as part of a trio led by the celebrated American jazz pianist Bill Evans was followed by an invitation to remain with the group when they returned to the US. This was in 1972, and permanent membership of the trio would have enhanced the young drummer’s prestige within the jazz world. Instead, he politely declined, believing that to accept would be an unacceptable diversion from his self-imposed task of developing musical languages as a player and composer.

The evidence of his resolve could be seen that same year in the cover picture of Ichnos, an album of Oxley’s music. It showed a drum kit that appeared to have been assembled in a junkyard, with the regular drums and cymbals accessorised by an upturned cooking pot, a washboard, a film reel, and various other steel and aluminium objects. Later a pair of bongos would replace the snare drum, and a new dimension was added by a giant custom-made cowbell.

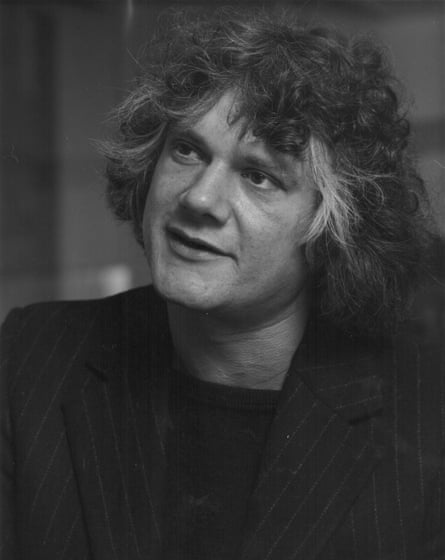

Oxley, who has died aged 85, was a master of the conventional kit and of the syntax and grammar of the most advanced modern jazz, his skills honed during several years as the house drummer at Ronnie Scott’s Club in London in the late 60s, accompanying the American stars who graced the Soho stage, from the saxophonist Sonny Rollins to the singer Blossom Dearie. But his creative philosophy could be summed up by his attitude to jazz musicians who settled for copying their American heroes, such as the drummer Art Blakey: “It doesn’t take you long to realise that there’s actually only one Art Blakey. If you can’t find something a bit closer to yourself, then it’s going to be a strained kind of life.”

With a stubbornness and a blunt response to criticism that recalled his South Yorkshire origins, Oxley followed his own path. It led towards a form of improvised music beyond category, in which he would be surrounded in live performance by an expanding array of sound sources, including electronics. Displaying a calm, precise technique and a highly developed understanding of the response and resonance of each surface he was striking, he rolled his sticks around them to create a dramatic sound-tapestry of effects, whether playing solo or with sympathetic collaborators, including the pianist Cecil Taylor, one of the father-figures of the 60s jazz avant-garde, and the saxophonist Anthony Braxton, a leading explorer of a subsequent generation.

Born into a working-class Sheffield family, Oxley played the piano for a while during childhood but took up the drums as a teenager. While playing in dance bands at night, he was sacked from his regular work in a cutlery-making firm for sleeping on the job.

National service took him into the Black Watch, the 3rd battalion of the Scottish Regiment, where his instrumental technique, sight-reading ability and all-round musicianship were polished while playing not just in military bands but in the regimental orchestra, using the full range of percussion – tympani, glockenspiel, triangle and so on – on the classical repertoire. Where most recruits saw national service as a chore, to Oxley it offered the chance to spend three years studying music without the burden of using it to earn a living.

After leaving the army he made several trips to New York as a member of a dance band playing for passengers on the Queen Mary, using shore leave to visit clubs and hear some of the leading figures of modern jazz at first hand. Between those trips he was playing in a cabaret band in Chesterfield, but by 1963 there were also Saturday afternoon gigs with a group of other aspiring young jazz musicians at a Sheffield pub called the Grapes.

Out of that came a regular group, whimsically named after an obscure English composer. The Joseph Holbrooke Trio consisted of Oxley, the guitarist Derek Bailey, a Sheffield neighbour, and a bassist, a Sheffield University philosophy student named Gavin Bryars. One thing they had in common, Bailey told his biographer, Ben Watson, was “an impatience with the gruesomely predictable.”

During this formative period they looked outside jazz for inspiration in the music of Webern, Stockhausen, Morton Feldman and John Cage. Oxley worked on a complex subdivision of the conventional 4/4 bar, superimposing quaver triplets on crotchet triplets to create a measure of 18 beats. He published his theory in Crescendo, the dance-band magazine, to general incomprehension.

When the group broke up in 1966, shortly after accompanying the American saxophonist Lee Konitz on a short tour, Bailey and Oxley made their separate ways to London, where the drummer joined the trio of the pianist Gordon Beck. Before long Ronnie Scott was making him an offer to become the club’s resident drummer and also to join Scott’s own bands, including an adventurous octet featuring promising younger players.

In 1969, on a widely praised album titled Extrapolation, the young guitarist John McLaughlin assembled a quartet including Oxley, the saxophonist John Surman and the bassist Brian Odgers to play rock-tinged music. But the drummer was also frequenting the Little Theatre Club in Covent Garden, where a more intense kind of musical experimentation was taking place in front of tiny but dedicated audiences.

Out of that came the two albums Oxley made in 1970 and 1971 for the CBS label. The first, called The Baptised Traveller, featured the trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, the saxophonist Evan Parker, the bassist Jeff Clyne, and Bailey, all regulars at the Little Theatre Club. Conceived as a four-part suite, with three compositions by Oxley sourrounding a piece called Stone Garden by the saxophonist Charlie Mariano, with whom Oxley had played at Scott’s, it remains a classic of British jazz of the period, an extended tone poem exquisite in its balance of unorthodox instrumental techniques with passages of graceful reflection.

Oxley was also a member of the saxophonist Alan Skidmore’s outstanding quintet, which in 1969 won awards at the Montreux jazz festival for best group, best soloist and best drummer. Oxley was also named best British jazz drummer by the readers of the Melody Maker, an award he won every year between 1969 and 1972. With the trio of the pianist Howard Riley, he began using amplification on his expanding kit.

When it became apparent that major record companies were no longer of a mind to record such music, in 1970 Oxley, Bailey and Parker launched their own independent label, Incus, which would go on to release more than 50 albums, continuing its activities even after disagreements provoked the departures first of Oxley and then of Parker.

Throughout the 70s Oxley was a regular tutor on the popular jazz course at the Barry summer school in south Wales, and in 1976 he taught improvisation as an artist in residence at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music in Australia. But the centre of his musical world was shifting to continental Europe, and particularly to Germany, which he had made his home. In 1988, he took part in a series of recording sessions in Berlin organised by the producer Jost Gebers to feature Taylor with various European musicians.

His successful duo session with Taylor began a musical relationship that lasted 20 years and included tours of the US and Europe, sometimes with the bassist William Parker in a group that became known as the Feel Trio. Among the duo’s albums was a set recorded at the Village Vanguard in New York in 2008.

Oxley continued to perform and record in a variety of settings, including the London Jazz Composers Orchestra, his own multinational Celebration Orchestra, a trio called SOH with Skidmore and the German bassist Ali Haurand, various groups with the pianists Paul Bley, Alexander von Schlippenbach and Stefano Battaglia and the trumpeters Bill Dixon, Enrico Rava and Tomasz Stanko, and a duo with the Scottish painter and musician Alan Davie, who gave him a violin which he added to his arsenal of percussion. The Joseph Holbrooke Trio reunited in 1998 for a radio broadcast in Cologne, released on Incus, and a subsequent studio recording in London.

Some of his later albums, such as The New World, a recording of electronic and acoustic percussion music released on the Discus label in 2023, featured his abstract paintings on their covers.

He is survived by his wife, Tutta.