When interviewing record executives during my three decades as pop critic for The Times, I noticed that they were as eager for publicity as any of their artists. And, I must confess, I appreciated it when they invariably said, “Call me anytime.” So, it was frustrating when the most important and respected record company president in town didn’t fall into that pattern.

The frustration increased over time as one Warner Bros. artist after another gushed about how much they adored Mo Ostin — including such Rock and Roll Hall of Fame members as Neil Young, Paul Simon, Fleetwood Mac, Randy Newman, Madonna, James Taylor and Tom Petty.

Over the years, I came to share their respect and affection for the man Frank Sinatra trusted in the early 1960s with the responsibility of running his new record company, Reprise, which soon became part of Warner Bros. Records. Sinatra started the label because he was disgruntled with executives at other labels and he wanted a company that put artists first. Instinctively, he sensed Ostin, a former bookkeeper at Verve Records in Los Angeles, could achieve that goal.

For almost four decades at the famed Warner Bros. offices in Burbank, Ostin, who died on Sunday at the age of 95, lived up to Sinatra’s trust, putting him high on the short list of towering U.S. label heads that includes the likes of Clive Davis, Ahmet Ertegun, David Geffen, Berry Gordy, Jimmy Iovine and Jerry Moss.

“It’s the end of an era, no question,” said Irving Azoff, the superstar manager who has guided the careers of such artists as the Eagles and Steely Dan. “Having the benefit of watching the record business change now for 50 years, I would unequivocally say I learned more from Mo than anyone else in the record business. More than anybody. he taught me how to respect artists, trust artists, and stay out of the creative process.”

Two members of Fleetwood Mac, whose ’70s blockbusters were quintessential Warners albums as well as rock ’n’ roll landmarks, told The Times via email about their affection and respect for Ostin.

“I have a crystal-clear memory of Fleetwood Mac walking in the front door of the Warner Bros. offices in 1975 and I can honestly say that my world changed instantly,” singer Stevie Nicks said. “Mo was loving and nurturing and had excellent musical taste, with boundless ideas and vision. He listened to artists and always put them first.”

“I looked to him as a friend first, who helped guide me and Fleetwood Mac into a place where we, like many others, were free to develop our music and have our creative needs met with wisdom and open arms,” added drummer Mick Fleetwood.

“I loved Mo,” Geffen said via email. “He was an important part of my life. I was honored that he joined with Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and me to build DreamWorks. We will not see his likes again in the music business.”

Neil Young, Lorne Michaels and Paul Simon applaud Mo Ostin’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003.

(Kevin Kane/WireImage)

Ostin was smart, classy and loyal. He chose employees with the same care that he signed artists, several of whom went on to become heads of labels, most notably Lenny Waronker, who was at Mo’s side at Warners and later at DreamWorks Records, where the pair signed such critically acclaimed newcomers as Elliot Smith and Rufus Wainwright as well as respected veterans, including George Michael and Randy Newman.

“I was fortunate to work with Mo for nearly four decades,” Waronker said Monday. “He was a phenomenal music man and a strong supporter of artists’ rights, but what I treasured most about Mo was his absolute fairness and his way of making everyone around him feel like part of his family. He made us all better.”

Newman, who was signed by Ostin in 1967, added, “I loved him. He was a great man.”

For decades, my admiration of Mo remained at a distance. In conversations, at concert receptions, he was unfailingly polite, but also unalterably off the record. Whenever I’d ask for a quote, he’d smile and point across the room to one of his artists. He didn’t change that policy until he decided to leave Warner Bros. in 1994 after a dispute with the new corporate owners of the label.

When The Times’ Chuck Philips and I contacted his office, we were delighted when Mo said he would sit down with us for what was his only formal interview at the label. He wanted to give his side of the Warner Bros. story. He was tired, he said, of the “revisionism” that had been circulating in the industry, anonymous criticisms in the media that Warners had fallen behind the times, comments he felt were spread by the corporate powers in New York.

The interview started with Ostin recalling Sinatra’s early goals.

“Frank’s whole idea was to create an environment which both artistically and economically would be more attractive for the artist than anybody else had to offer,” he said. “That wasn’t how it was anywhere else. You had financial guys, lawyers, marketing guys. Their priorities may not have been the music. One of the great things about Warners, I always felt, was our emphasis and priority was always about the music.”

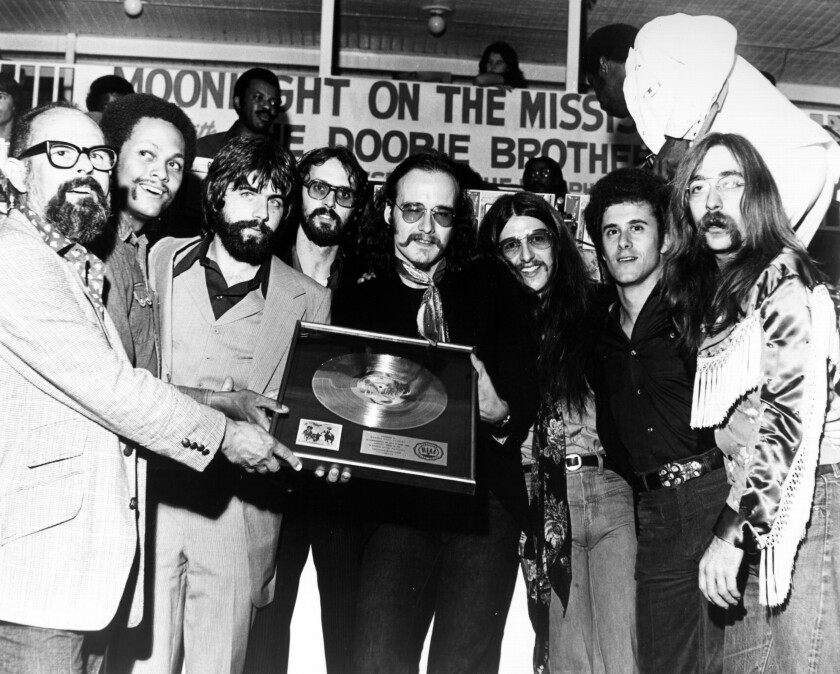

Mo Ostin, left, presents a gold record to the Doobie Brothers’ Tiran Porter, Michael McDonald, Keith Knudson, John Hartman, Patrick Simmons, manager Bruce Cohn and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter in 1975.

(Michael Ochs Archives)

Ostin helped steer Warner/Reprise into a powerhouse that was the envy of the record world. In the process, Warners brought credibility to Los Angeles at a time when it was considered a minor player in the industry, leading the way for the westward tilt of the music business from New York to Los Angeles.

As word leaked out in recent months about Ostin’s failing health, some of the classic Warners artists stopped by his home in Pacific Palisades for brief visits, including Simon, who jumped in the early 1980s from rival New York-based Columbia Records to Warners because of his faith in Ostin. After two coolly received records for Ostin and Warners, that faith was rewarded in 1986 when Simon released the groundbreaking “Graceland,” which won album of the year at the Grammys and became his best-ever-selling solo LP.

“Absolutely the nicest guy,” Simon said of Ostin. “One of the great record executives and my dear, dear friend. He lived a good, long life, but I would have enjoyed another 10, 20 years of Mo.”

Robert Hilburn was pop music critic for The Times from 1970 to 2005.