Mo Ostin, the music executive who helped transform Warner Bros. Records into one of the most admired music labels in the world and who earned respect and lasting allegiance from musicians from Los Angeles to London for his artist-friendly philosophy, died on Sunday. He was 95.

His death was confirmed by multiple sources close to the executive. The cause of death was age-related.

During his 31-year career at Warner Bros., Ostin advocated for changes that would help the then-small record label challenge and ultimately outpace industry leaders during the ’60s and ’70s, an era of adventuresome and varying musical styles. From Frank Sinatra to Jimi Hendrix to Prince, Ostin coaxed a wide variety of musicians to the label, and then gave them the elbow room they needed to be creative.

But in the late 1990s, when downloads replaced actual records and piracy cut into industry margins, Ostin chafed under the growing corporate culture at Warner Bros. and walked away, only to team up a year later with former rival David Geffen at DreamWorks and return as a dominant figure in the recording industry.

“Unlike other executives we talked to, Mo seemed genuinely interested in our music,” Mike Mills, the former bass player with R.E.M., told The Times. “But the best thing about him was that he seemed honest. So we trusted him and it paid off — in spades.”

Dean Martin, from left, Mo Ostin, Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr.

(Warner Records Archives)

He was born Morris Meyer Ostrofsky on March 27, 1927, in New York City, to immigrant parents who’d fled Russia during the revolution. Ostin was 13 when he and his family, including his younger brother Gerald, moved to Los Angeles and opened a tiny produce market near the Fairfax Theatre.

Ostin attended Fairfax High School and then UCLA, where he earned a degree in economics. He attended UCLA Law School but dropped out to support his wife, Evelyn, and his young son.

A childhood neighbor, Irving Grankz, led him in the direction of music. Grankz’s brother, Norman, owned Clef Records, whose stable of jazz stars included Charlie Parker, Count Basie and Duke Ellington. Before long, Ostin — who changed his last name because people seemed to stumble on Ostrofsky — was the company’s controller.

In the late 1950s, Sinatra tried to buy Verve Records, which had taken over Clef. The label eventually sold out to MGM Records, and Sinatra decided to start his own recording label, Reprise Records, and asked Ostin to lead his new enterprise.

By 1963, Sinatra sold his company to film mogul Jack Warner. Ostin, partnered with Warner Bros. Records, helped bring on important acts, including British rock band the Kinks, which he personally signed on. The band’s success — six top 40 U.S. singles — motivated him to pursue the rock genre. Artists such as Jimi Hendrix, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Fleetwood Mac, R.E.M., Madonna, Paul Simon, Talking Heads and the Red Hot Chili Peppers followed.

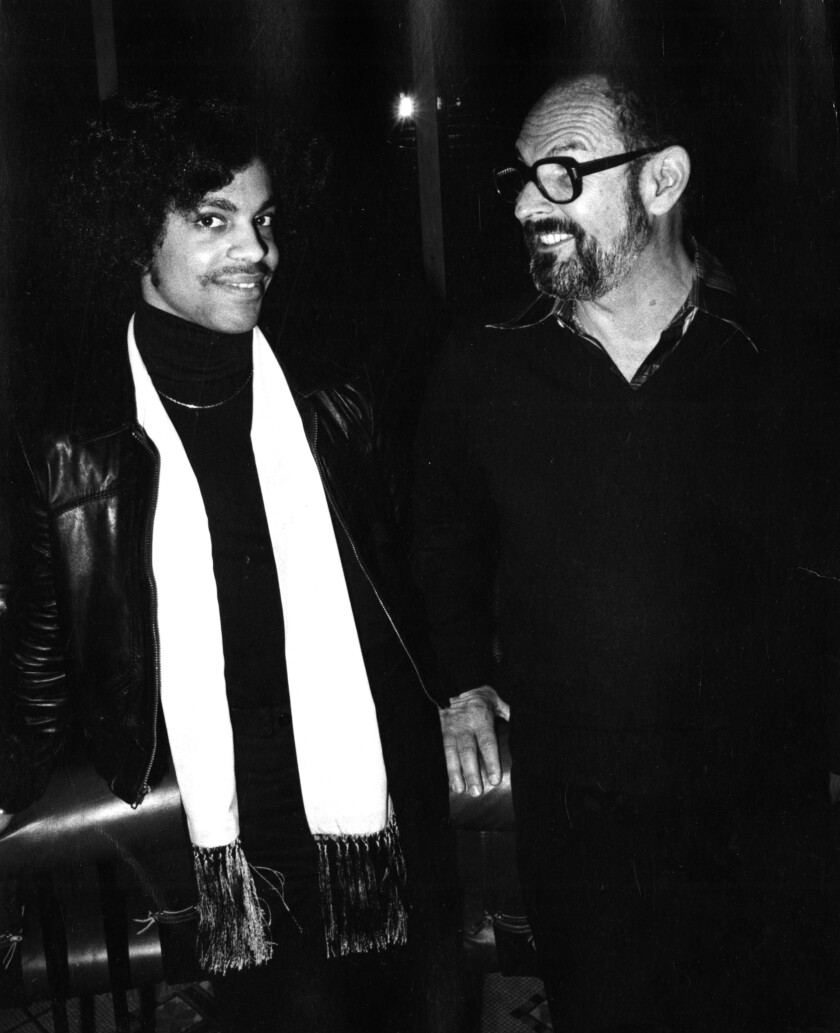

Prince with Mo Ostin circa late 1970s.

(Warner Records Archives)

He told Billboard magazine years after he retired that he trusted Prince so implicitly that he often would not hear the music he was working on until the musician came into his office and played the finished product, often singing along as Ostin listened.

“The thing you’ve got to learn is trust your instincts,” Ostin said in a December 1994 interview with The Times’ Robert Hilburn and Chuck Philips, the first formal one he granted during his three-decade career at the company.

Ostin, who was named CEO and chairman of Warner Bros. Records in the ’70s, had a reputation for avoiding interviews; it took years of requests and lobbying from friends to get him to even agree to the single meeting with The Times. During the interview, he admitted that avoiding the media was “a personal hang-up” and that to him, “The artist is the person who should be in the foreground.”

His attitude toward building an artist-oriented company — a philosophy shaped by his time working with Sinatra — was why many artists remained loyal to Ostin. He told The Times that he believed the business was about freedom and creative control.

“Part of our hallmark has always been to work with controversial artists, artists who were on the edge, artists who people thought were weird,” Ostin told The Times.

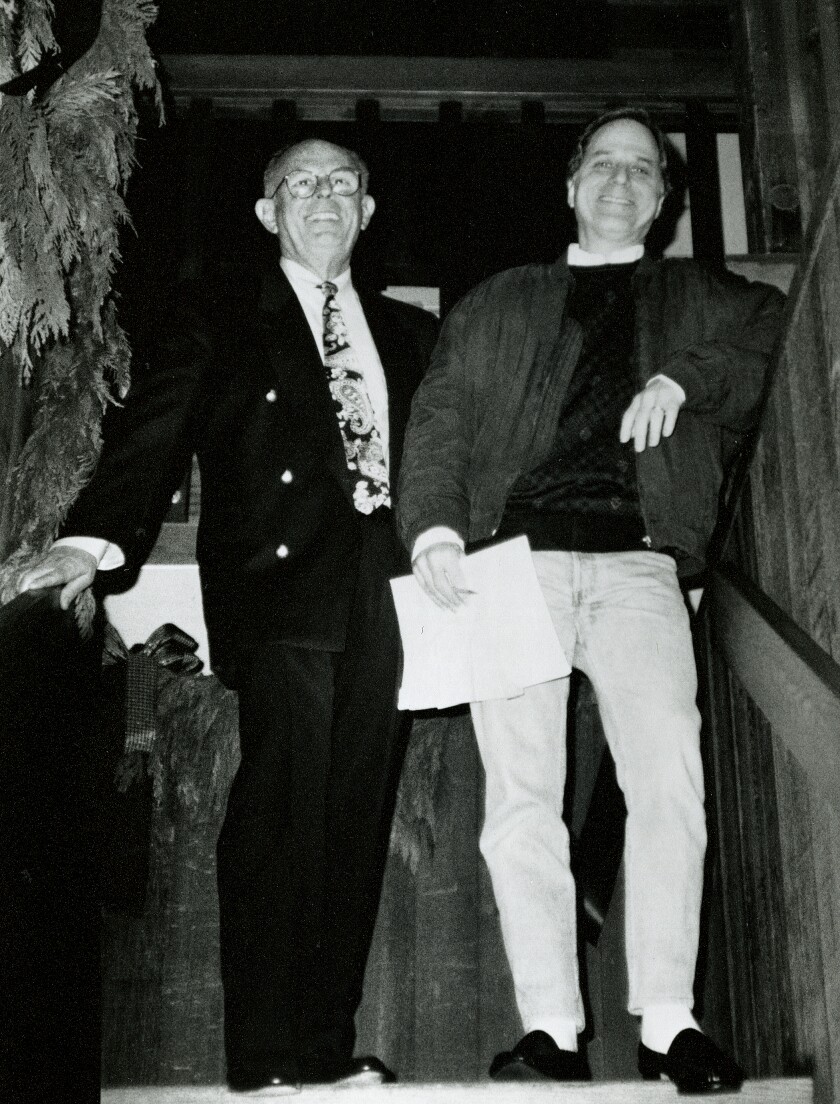

Mo Ostin, left, and Lenny Waronker in 1991.

(Warner Records Archives)

But by the mid-1990s, Ostin said Warner Bros. Records had become a different company than the one he had groomed. When asked to cut his payroll, Ostin balked.

“Yeah, we might have been able to slash some overhead and make a little bit more money. You can always do that if you’re a penny-pincher,” Ostin said.

Warner Bros. begged him to stay, offering him a three-year extension. But Ostin had had enough. Simon and Young were among the artists who stood by his side as the feud became public.

“It was the toughest thing I’ve ever been through in the business — and it shook me to the core,” Ostin said.

But his time away was short-lived.

In October 1995, Ostin confirmed he was joining the newly founded record company partnership DreamWorks SKG, started by Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen, whom Ostin had competed with fiercely but whose admiration he had also earned. Ostin’s son Michael and longtime colleague Lenny Waronker, both former Warner Bros. Record executives, joined him.

“The idea of starting over from scratch, of doing something fresh, of redefining my life at this stage of my career is very appealing to me,” Ostin told The Times.

While he headed DreamWorks SKG, the company signed on talents like Nelly Furtado, Papa Roach and Jimmy Eat World before it sold to Universal Music Group’s Interscope Records in 2004. Ostin retired soon after.

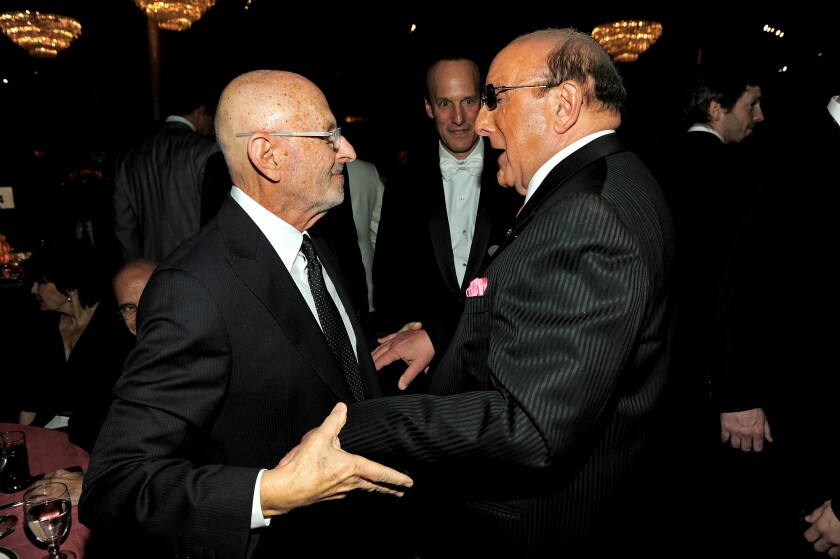

Mo Ostin, left, and Clive Davis in 2011.

(Larry Busacca)

In 2003, Ostin was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, where he was introduced by Young and Simon.

“A record exec who knows music is more than a business” is how the hall of fame described him. “He encourages creativity and risk-taking and knows a future star when he hears one.”

In 2006, Ostin was awarded the President’s Merit Award from the Recording Academy at its Grammy Salute to Industry Icons for his contribution to shaping the modern music industry.

In 2018, Ostin was recognized and given an award for his long and successful career during the 17th Silverlake Conservatory of Music gala. That night, Anthony Kiedis, co-founder of the music school, said of Ostin: “Mo is beyond historically important to this world. … It was because he loved music. It was his giving heart that cared about music that inspired us to want to make great records and enabled us to want to start this school.”

A longtime L.A. philanthropist, Ostin and his wife donated nearly $25 million to UCLA. Two of their largest contributions include $10 million for the Evelyn and Mo Ostin Music Center and $10 million toward the Mo Ostin Basketball Center. At UCLA, he served on the board of the School of the Arts and Architecture and the Herb Alpert School of Music. At USC, he served on the Thornton School of Music’s Board of Councilors, an advisory panel to the school’s administration.

Ostin is survived by his son Michael. Sons Kenny and Randy died in 2004 and 2013, respectively; his wife, Evelyn, died in 2005.